The great Russian filmmaker Andrei Tarkovsky made only seven feature films in his short life. (Find most of them online here.) But before making those, he directed and co-directed three films as a student at the All-Union State Cinema Institute, or VGIK. Those three films, when viewed as a progression, offer insights into Tarkovsky’s early development as an artist and his struggle to overcome the constraints of collectivism and assert his own personal vision.

The Killers, 1956:

Tarkovsky was fortunate to enter the VGIK when he did. As he arrived at the school in 1954 (after first spending a year at the Institute of Eastern Studies and another year on a geological expedition in Siberia) the Soviet Union was entering a period of liberalization known as the “Krushchev Thaw.” Joseph Stalin had died in 1953, and the new Communist Party First Secretary, Nikita Khrushchev, denounced the dead dictator and instituted a series of reforms. As a result the Soviet film industry was entering a boom period, and there was a huge influx of previously banned foreign movies, books and other cultural works to draw inspiration from. One of those newly accessible works was the 1927 Ernest Hemingway short story, “The Killers.”

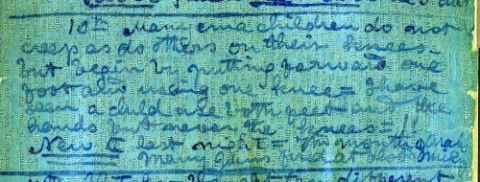

Tarkovsky’s adaptation of Hemingway’s story (see above) was a project for Mikhail Romm’s directing class. Romm was a famous figure in Soviet cinema. There were some 500 applicants for his directing program at the VGIK in 1954, but only 15 were admitted, including Tarkovsky. In The Films of Andrei Tarkovsky: A Visual Fugue, Vida T. Johnson and Graham Petrie describe the environment in Romm’s class:

Romm’s most important lesson was that it is, in fact, impossible to teach someone to become a director. Tarkovsky’s fellow students–his first wife [Irma Rausch] and his friend, Alexander Gordon–remember that Romm, unlike most other VGIK master teachers, encouraged his students to think for themselves, to develop their individual talents, and even to criticize his work. Tarkovsky flourished in this unconstrained environment, so unusual for the normally stodgy and conservative VGIK.

Tarkovsky worked with a pair of co-directors on The Killers, but by all accounts he was the dominant creative force. There are three scenes in the movie. Scenes one and three, which take place in a diner, were directed by Tarkovsky. Scene two, set in a boarding house, was directed by Gordon. Ostensibly there was another co-director, Marika Beiku, working with Tarkovsky on the diner scenes, but according to Gordon “Andrei was definitely in charge.” In a 1990 essay, Gordon writes:

The story of how we shot Hemingway’s The Killers is a simple one. In the spring Romm told us what we would have to do–shoot only indoors, use just a small group of actors and base the story on some dramatic event. It was Tarkovsky’s idea to produce The Killers. The parts were to be played by fellow students–Nick Adams by Yuli Fait, Ole Andreson the former boxer, of course, by Vasily Shukshin. The murderers were Valentin Vinogradov, a directing student, and Boris Novikov, an acting student. I played the cafe owner.

The filmmakers scavenged various props from the homes of friends and family, collecting bottles with foreign labels for the cafe scenes. The script follows Hemingway’s story very closely. While two short transitional passages are omitted, the film otherwise matches the text almost word-for-word. In the story, two wise-cracking gangsters, Al and Max, show up in a small-town eating house and briefly take several people (including Hemingway’s recurring protagonist Nick Adams) hostage as they set up a trap to ambush a regular customer named Ole Andreson. One notable departure from the source material occurs in a scene were the owner George, played by Gordon, nervously goes to the kitchen to make sandwiches for a customer while the gangsters keep their fingers on the triggers. In the story, Hemingway’s description is matter-of-fact:

Inside the kitchen he saw Al, his derby cap tipped back, sitting on a stool beside the wicket with the muzzle of a sawed-off shotgun resting on the ledge. Nick and the cook were back to back in the corner, a towel tied in each of their mouths. George had cooked the sandwich, wrapped it up in oiled paper, put it in a bag, brought it in, and the man had paid for it and gone out.

In Tarkovsky’s hands the scene becomes a cinematic set piece of heightened suspense, as the customer waiting at the counter (played by Tarkovsky himself) whistles a popular American tune, “Lullaby of Birdland,” while the nervous cafe owner makes his sandwiches. Our point of view shifts from that of George, who glances around the kitchen to see what is going on, to that of Nick, who lies on the floor unable to see much of anything. “Tarkovsky was serious about his work,” writes Gordon, “but jolly at the same time. He gave the camera students, Alvarez and Rybin, plenty of time to do the lighting well. He created long pauses, generated lots of tension in those pauses, and demanded that the actors be natural.”

There Will Be No Leave Today, 1958:

Tarkovsky and Gordon again collaborated on There Will Be No Leave Today, which was a joint venture between the VGIK and Soviet Central Television. “The film was no more than a propaganda film, intended to be aired on television on the anniversary day of the World War II victory over the Germans,” said Gordon in a 2003 interview. “At the time, there was only one TV station and it would often screen propaganda material on the greatnesses of the USSR. This particular film was broadcast on TV for at least three consecutive years. But this did not make the film particularly famous, because you could see films like that on TV all day, at the time.”

There Will Be No Leave Today is based on a true story about an incident in a small town where a cache of unexploded shells, left over from the German occupation, was discovered and–after some drama–removed. The production was far more ambitious than that of The Killers, involving a combination of professional and amateur actors, hundreds of extras, and various shooting locations. It was filmed in Kursk over a period of three months, and took another three months to edit. Gordon provided more details:

With respect to the contribution done by the two directors–I and Andrei–I believe that Andrei contributed the majority. We wrote the script together right at the start. There was an additional scriptwriter, who was subsequently replaced by another group of scriptwriters. Collaboration was very good during this first stage. During the second stage, Andrei finished up the script, with the scenes in the hospital and the story of the volunteer who detonates the bomb–these ideas were Andrei’s. It was a jovial atmosphere, we discussed the scenes in the evening. The main storyline was created in the beginning, when we wrote the script, and no great changes were made to it. It was very easy work.

Despite the scope of the story, and occasional comparisons to Henri-Georges Clouzot’s 1953 thriller The Wages of Fear, it’s clear that neither Gordon nor Tarkovsky took the film very seriously. It was simply a learning exercise. Perhaps the only surprising thing is that Tarkovsky, who would later struggle bitterly with Soviet bureaucrats over the artistic integrity of his work, would submit so readily to making a propaganda film. “VGIK proposed that we make a practice film intended for TV audiences, a propaganda piece on the victory of the USSR over the Germans,” said Gordon, “and we just chose an easy, uncomplicated script. We did not set out to do a masterpiece. Our focus was on learning the elementaries of filmmaking, through making a film that was relatively uncomplicated and also easy for the people to consume. Andrei was happy with this. He had no problems with this approach.”

The Steamroller and the Violin, 1960:

Watch the full film here.

Tarkovsky’s first work as sole director, The Steamroller and the Violin, is an artistically ambitious film, one that in many ways foreshadows what was later to come. As Robert Bird writes in Andrei Tarkowski: Elements of Cinema:

When the door opens in the first shot of Steamroller and Violin one senses the curtain going up on Andrei Tarkovsky’s career in cinema. Out of this door will proceed an entire line of characters, from the medieval icon-painter Andrei Rublëv to the post-apocalyptic visionaries Domenico and Alexander. It will open onto native landscapes and alien words, onto scenes of medieval desolation and post-historical apocalypse, and onto the innermost recesses of conscience. Yet, for the moment, the open door reveals only a chubby little schoolboy named Sasha with a violin case and music folder, who awkwardly and tentatively emerges into the familiar, if hostile courtyard of a Stalin-era block of flats.

The young director expressed his plan for The Steamroller and the Violin in an interview with a polish journalist, later translated into English by Trond S. Trondsen and Jan Bielawski at Nostalghia.com:

Although it’s dangerous to admit–because one doesn’t know whether the film will be successful–the intent is to make a poetic film. We are basing practically everything on mood, on atmosphere. In my film there has to be a dramaturgy of image, not of literature.

The project was Tarkovsky’s “diploma film,” a requirement for graduation. He wrote the script with fellow student Andrei Konchalovsky over a period of more than six months. It tells the story of a friendship between a sensitive little boy, who is bullied by other children and stifled by his music teacher, and a man who operates a steamroller at a road construction site near the child’s home. The boy needs a father figure. The man is emotionally troubled by his wartime experiences and finds solace in work. He resists the flirtations of women. When he sees a group of children bullying the boy on his way to a violin lesson, he comes to the child’s aid and they become friends. “Those two people, so different in every respect,” said Tarkovsky, “complement and need one another.”

The film marks the beginning of Tarkovsky’s cinematic obsession with metaphysics. According to Trondsen and Bielawski, “VGIK archive documents reveal that the director’s intention with The Steamroller and the Violin was to chart the attempts at contact between two very different worlds, that of art and labor, or, as he referred to it as, ‘the spiritual and the material.’ ” The inner world of the boy is suggested in prismatic effects of light sparkling through water and glass and images split into multiples. The worker’s world, by contrast, is concrete and earth.

When Tarkovsky finished his film, not everyone at Mosfilm, the government agency that funded the project, liked what they saw. “Surprisingly,” writes Bird, “it was Tarkovsky’s subtle innovation in this seemingly harmless short film that inaugurated the adversarial tone that subsequently came to dominate his relationship with the Soviet cinema authorities. Unlikely as it seems, Steamroller and Violin was hounded from pillar to post by vigilant aesthetic watchdogs and was lucky to have been released at all.” As part of the process of earning his degree, Tarkovsky had to defend his film during a meeting of the artistic council of the Fourth Creative Unit of Mosfilm on January 6, 1961. The criticisms were varied, according to Bird, but much of it came down to resentment over the portrayal of a socially elite rich boy in contrast to a poor worker. Tarkovsky’s response to his critics was captured by a stenographer:

I don’t understand how the idea arose that we see here a rich little violinist and a poor worker. I don’t understand this, and I probably never will be able to in my entire life. If it is based on the fact that everything is rooted in the contrast in the interrelations between the boy and the worker, then the point here is the contrast between art and labor, because these are different things and only at the stage of communism will man find it possible to be spiritually and physically organic. But this is a problem of the future and I will not allow this to be confused. This is what the picture is dedicated to.

Despite the backlash at Mosfilm, the authorities at the VGIK were impressed. Tarkovsky graduated with high marks, and over time the film has acquired the respect and appreciation its maker desired. “The Steamroller and the Violin,” write Trondsen and Bielawski, “must be regarded as an integral part of Tarkovsky’s oeuvre, as it is indeed ‘Tarkovskian’ in every sense of the word.”

NOTE: All three student films will now be included in our popular collection of Free Tarkovsky Films Online.

Related content:

Stanley Kubrick’s Very First Films: Three Short Documentaries

Martin Scorsese’s Very First Films: Three Imaginative Short Works