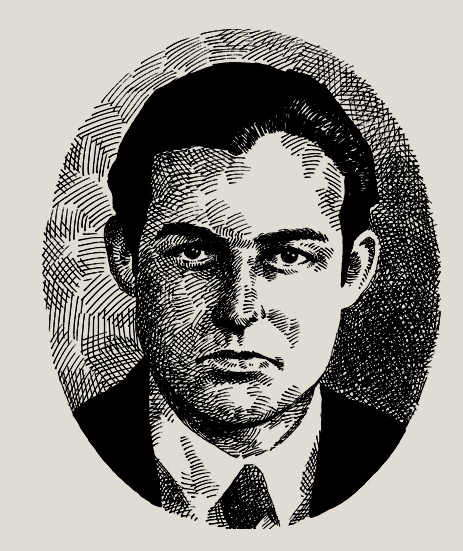

Studs Terkel would have turned 100 years old today. A legendary broadcaster and the author of ground-breaking oral histories of the American experience in the 20th century–including his Pulitzer Prize-winning examination of World War II, The Good War–Terkel was a beloved cultural figure in his native Chicago up until his death in October, 2008. The headline of his New York Times obituary called him “Listener to Americans.” It was an apt phrase. “The thing I’m able to do, I guess, is break down walls,” Terkel once said. “If they think you’re listening, they’ll talk. It’s more of a conversation than an interview.” With Studs, they talked.

To celebrate his 100th birthday we bring you a little clip from the “Eight Forty-Eight” show on Chicago public radio station WBEZ, with a listener calling in from his car to play a reading by Terkel of a poem written by Pete Seeger and Jim Musselman called “Blessed be the Nation.” It’s from the 1998 tribute album Where Have All the Flowers Gone: The Songs of Pete Seeger. The brief clip reveals something of Terkel’s values, and of the esteem in which he is still held in the Windy City and beyond.