The Conversation, Apocalpyse Now, The Godfather — Francis Ford Coppola’s movies come so big that even the most casual cinephiles vividly remember their first experiences with them. Of course, Coppola made all of those in the seventies, when he held down the position of one of the leading lights of the New Hollywood movement, when major American studios grew willing to tap the unconventional but ultimately formidable cinematic talents of a variety of young auteurs. They backed everyone from Coppola to Martin Scorsese to Peter Bogdanovich to Michael Cimino, and we enjoy the fruits of their gamble even today. Enthusiasts of American cinema remember that period — along with its echo, the Sundance-Miramax-driven “indie” boom of the nineties — as a golden age. Coppola hasn’t stopped making films, and even if his latter-day projects like Youth Without Youth and Tetro haven’t gained such iconic stature in the culture, something in them nevertheless lodges in your mind, demanding further viewing and reflection.

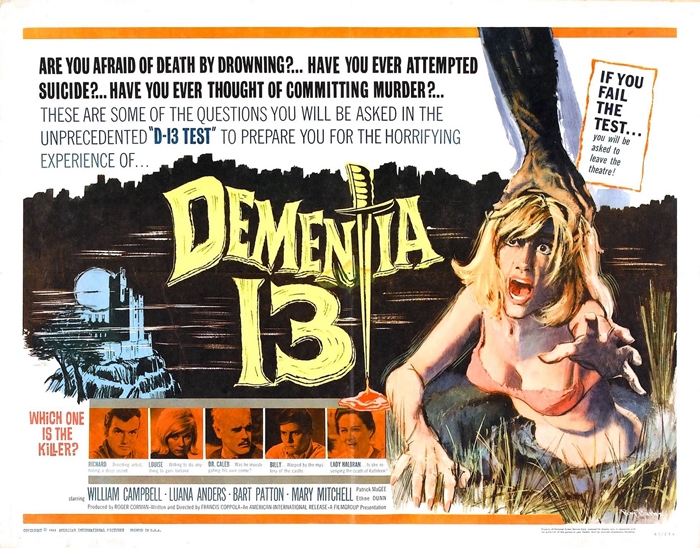

You’ll find an equally fascinating example of Coppola’s work if you look before the New Hollywood era, all the way back to a 75-minute piece of black-and-white psychological horror called Dementia 13. Watch it in its entirety on YouTube for both the formative piece of Coppola’s art and the 1963 piece of Roger Corman-produced junk that it somehow is. The picture represents a transition point between the young Coppola, sound technician and director of “nudie” films, and the mature Coppola, lauded with critical and commercial acclaim but subject to an almost self-destructive grandness of ambition. Corman, who had $22,000 laying around after his last production, asked Coppola for a Psycho knockoff. Coppola proceeded to round up a few of his UCLA pals and shoot Dementia 13 in Ireland, returning with an altogether more subtle and subdued movie than Corman could have expected. (Not that it’s particularly hard to overshoot Roger Corman-style expectations in those departments.)

To watch Dementia 13 now is to witness Coppola’s control of tension and darkness in its embryonic — but still impressive — form. Nobody involved in the production could have deluded themselves about its goal of shooting a few maximally gruesome axe murders as quickly and cheaply as possible, but even such straitened circumstances allow for pockets of artistry to bubble through. Emerging from the school of cheap thrills into ultimate respectability wasn’t an unknown story for Coppola’s cinematic generation. Today’s serious young directors seem to prefer honing their chops with now-inexpensive video gear, making films that cost far less than $22,000 and thus avoiding compromising their sensibilities. That strikes me as a step forward, but watching movies in the class of this unlikely Corman-Coppola partnership will always make you wonder what we’ve lost now that our best filmmakers don’t have to pay their dues in the wild world of schlock.

Colin Marshall hosts and produces Notebook on Cities and Culture. Follow him on Twitter at @colinmarshall.