“By the end of the eighteenth and the beginning of the nineteenth century, the gloomy festival of punishment was dying out… Punishment, then, will tend to become the most hidden part of the penal process.” — Michel Foucault

The study of crime in the late 1800s began with racist pseudoscience like craniometry and phrenology, both of which have made a disturbing comeback in recent years. In his 1876 book, Criminal Man, the “father of criminology,” Cesare Lombrosco, defined “the criminal” as “an atavistic being who reproduces in his person the ferocious instincts of primitive humanity and the inferior of animals.” Lombrosco believed that certain cranial and facial features correspond to a “love of orgies and the irresistible craving for evil for its own sake, the desire not only to extinguish life in the victim, but to mutilate the corpse, tear its flesh, and drink its blood.” That such descriptions preceded Bram Stoker’s Dracula by several years may be no coincidence at all.

No such thing as a natural criminal type exists, but this has not stopped 19th century prejudices from embedding themselves in law enforcement, the prison system and the culture at large in the United States. Outside of the most sensationalist cases, however, we rarely hear from incarcerated people themselves, though they’ve had plenty say about their humanity in print since the turn of the 19th century, when the first prison newspaper, Forlorn Hope, was published in New York City on March 24, 1800.

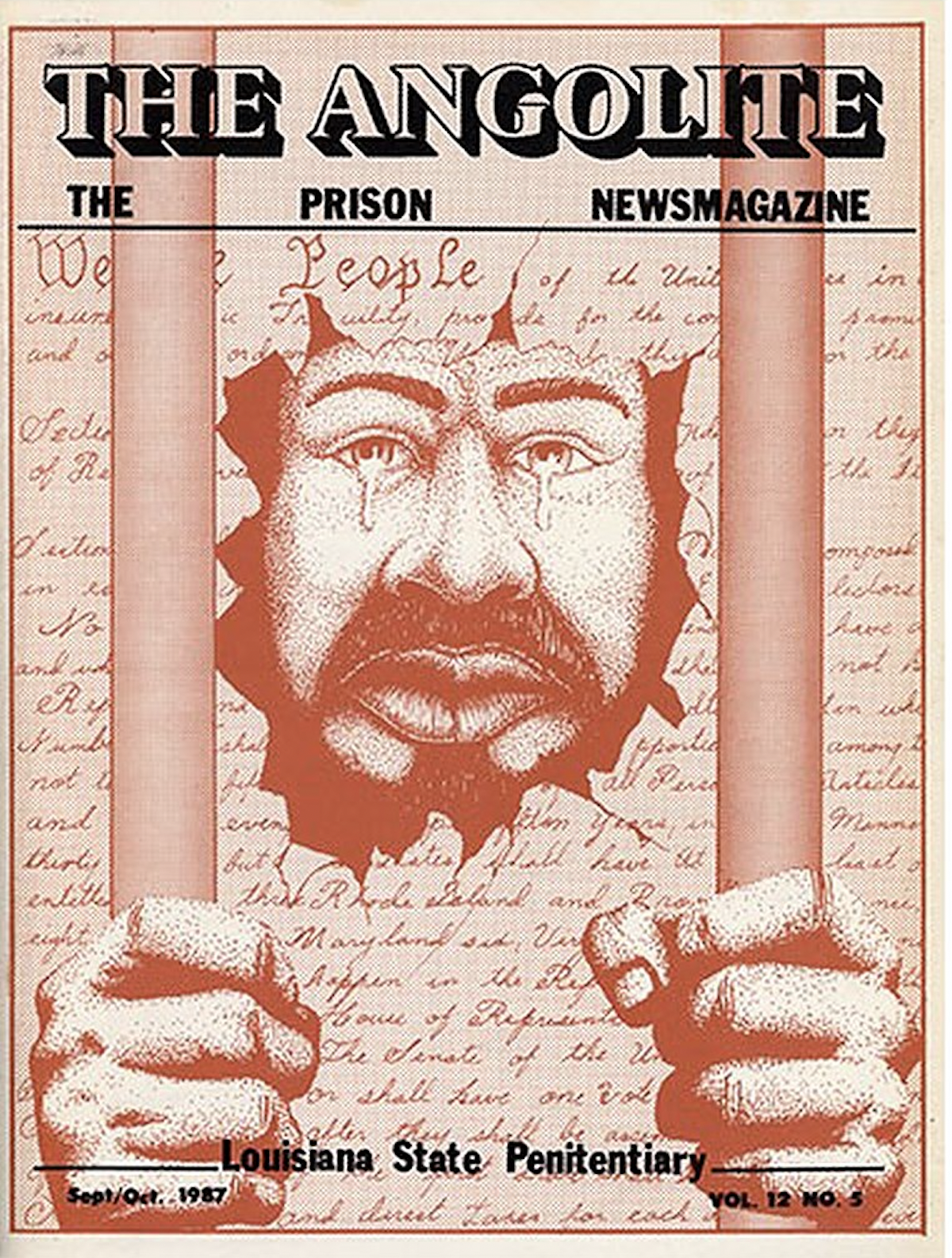

“In the intervening 200 years,” notes JSTOR, “over 500 prison newspapers have been published from U.S. prisons.” A new collection, American Prison Newspapers: 1800–2020 — Voices from the Inside, “will bring together hundreds of these periodicals from across the country into one collection that will represent penal institutions of all kinds, with special attention paid to women-only institutions.”

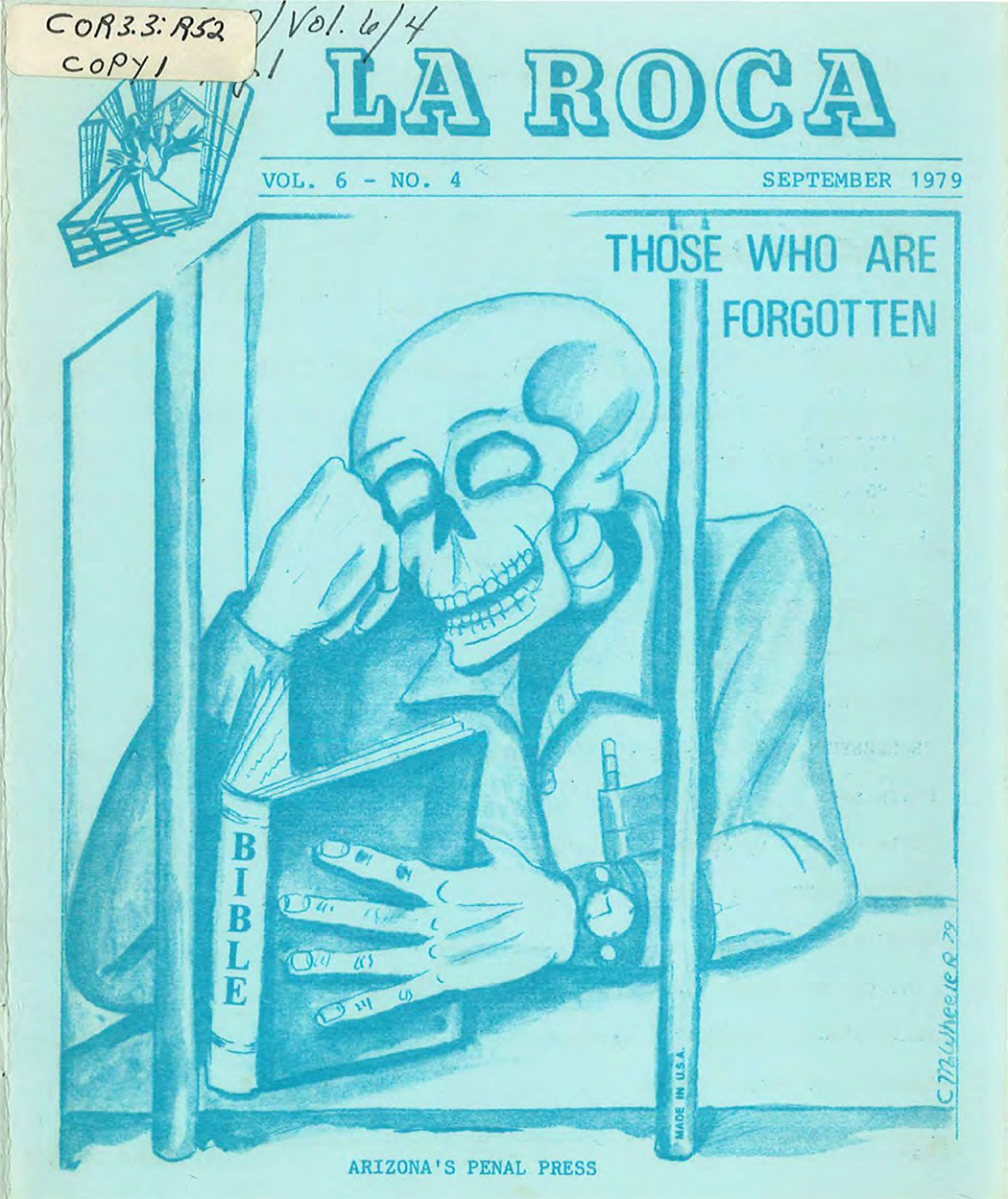

The U.S. incarcerates “over 2 million as of 2019” — and has produced some of the world’s most moving jail and prison literature, from Thoreau’s “Civil Disobedience” to Martin Luther King, Jr.‘s “Letter from a Birmingham Jail.” The newspapers in this collection do not often feature a similar level of literary bravura, but many show a high degree of professionalism and artistic quality. “Next to the faded, home-spun pages of The Hour Glass, published at the Farm for Women in Connecticut in the 1930s,” writes JSTOR Daily’s Kate McQueen, “readers will find polished staples of the 1970s like newspaper The Kentucky Inter-Prison Press and Arizona State Prison’s magazine La Roca.”

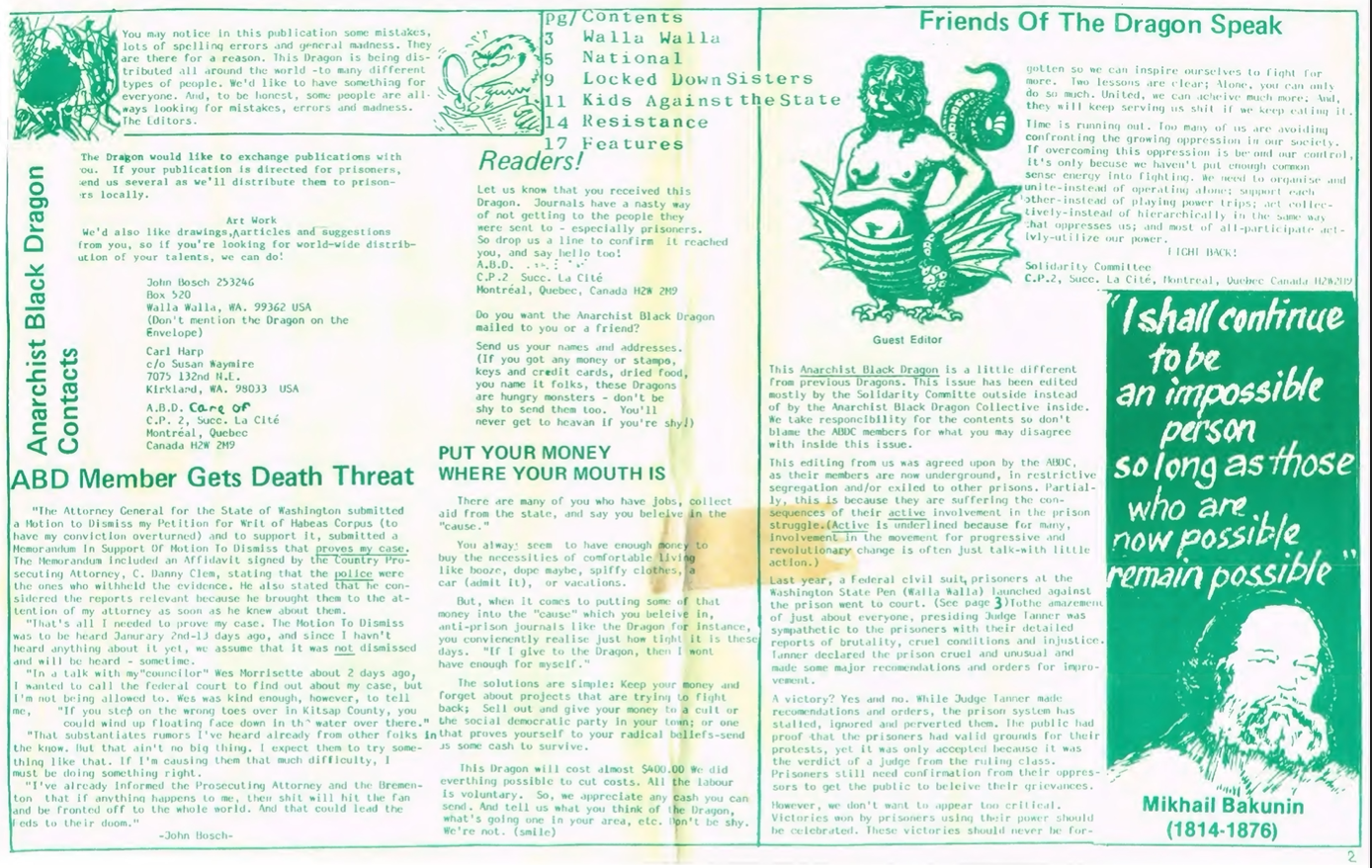

Many, if not most, of these publications were published with official sanction, and these “cover similar ground. They report on prison programing, profile locals of interest, and offer commentary on topics like parole and education” under the watchful gaze of the warden, whose photograph might appear on the masthead. “Incarcerated journalists walk a tightrope between oversight by administrations — even censorship — and seeking to report accurately on their experiences inside,” the collection points out. Prison newspapers gave inmates opportunities to share creative work and hone newly acquired literacy, literary, and legal skills. Those periodicals that circulated underground without the authorities’ permission had no need to equivocate about their politics. Washington State Penitentiary’s Anarchist Black Dragon, for example, took a fiercely radical stance on every page. Nowhere on the masthead will one find the names of correctional officers, or even a list of editors and contributors, or even a masthead.

Whether official, unofficial, or occupying a grey area, prison periodicals all hoped in some degree to “poke holes in the wall,” as Tom Runyon, editor of Iowa State Penitentiary’s Presidio wrote — reaching audiences outside the prison to refute criminological thinking. Arizona State Prison’s The Desert Press, led its January 1934 issue with the pressing headline “Are Convicts People?” (likely after Alice Duer Miller’s satirical 1904 “book of rhymes for suffrage times,” Are Women People?) Lawrence Snow, editor of Kentucky State Penitentiary’s Castle on the Cumberland, picked up the question with more formality in a 1964 column, asking, “How shall [a prison publication] go about its principal job of convincing the casual reader that convicts, although they have divorced themselves temporarily from society, still belong to the human race?” Given that the United States imprisons more people than any other nation in the world, the question seems more pertinent — urgent even — than ever before. Enter the American Prison Newspapers collection here.

via Kottke

Related Content:

On the Power of Teaching Philosophy in Prisons

Prisons Around the U.S. Are Banning and Restricting Access to Books

Bertrand Russell’s Prison Letters Are Now Digitized & Put Online (1918 – 1961)

Patti Smith Reads from Oscar Wilde’s De Profundis, the Love Letter He Wrote From Prison (1897)

Josh Jones is a writer and musician based in Durham, NC. Follow him at @jdmagness

Leave a Reply