Here in Korea, where I live, cat owners aren’t called cat owners: they’re called goyangi jibsa, literally “cat butlers.” Clearly the idea that felines have flipped the domestic-animal script, not serving humans but being served by humans, transcends cultures. It also goes far back in history: witness the 12th-century verses recently tweeted out in translation by writer Xiran Jay Zhao, in which “Song dynasty poet Lu You” — one of the most prolific literary artists of his time and place — “poem-liveblogged his descent from cat owner to cat slave.”

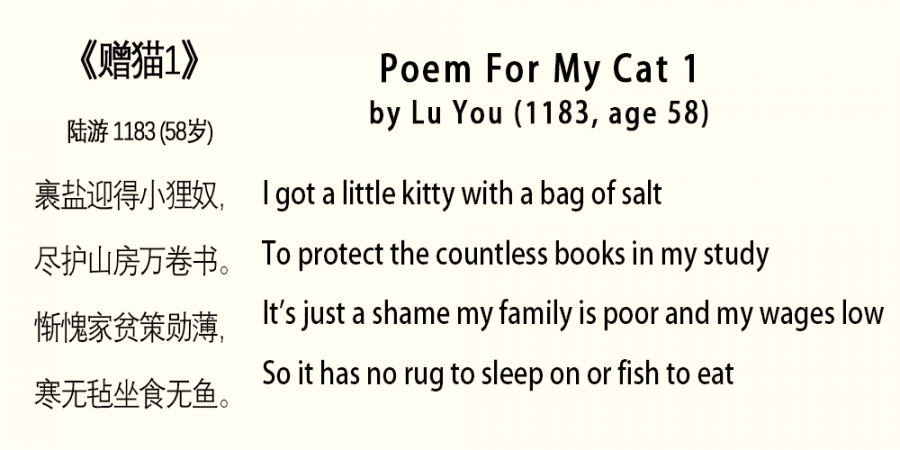

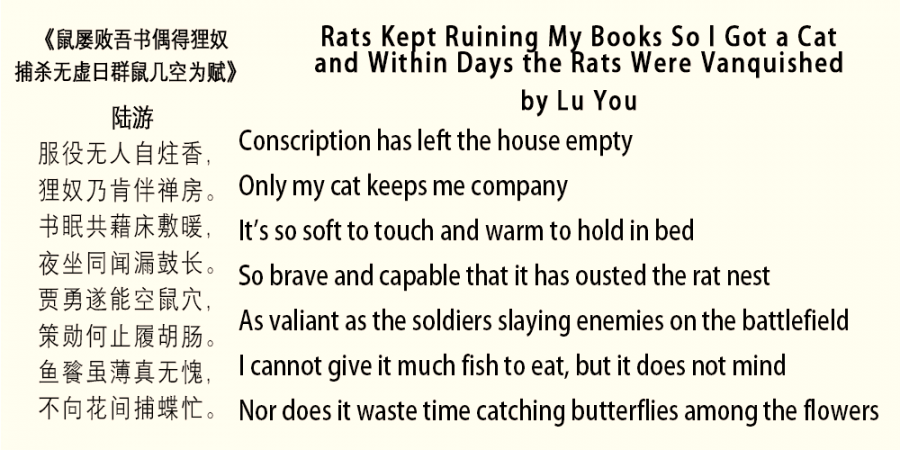

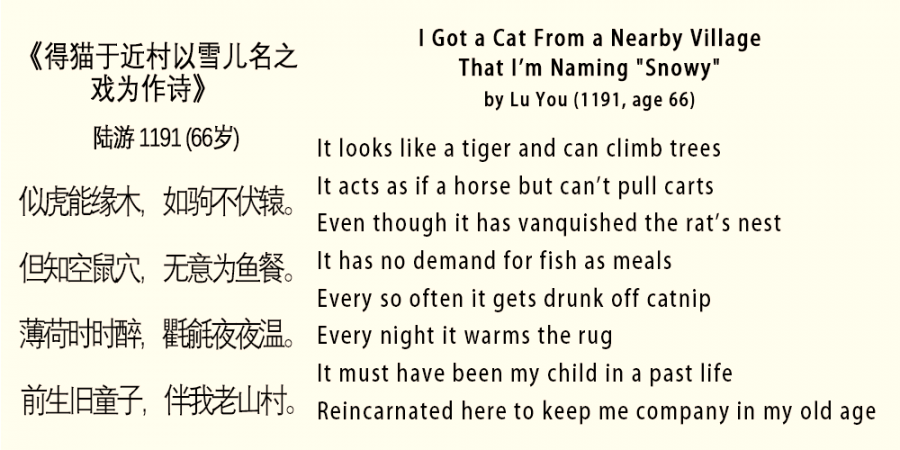

The story begins in 1138, writes Zhao, when “Down On His Luck scholar-official Lu You gets a cat because rats keep munching on his books.” The eight poems in this series begin with praise for the animal — “It’s so soft to touch and warm to hold in bed / So brave and capable that it has ousted the rat nest” — and goes on to describe the cats he subsequently acquires, who selflessly vanquish the household rats while indulging in nothing more than the occasional catnip binge.

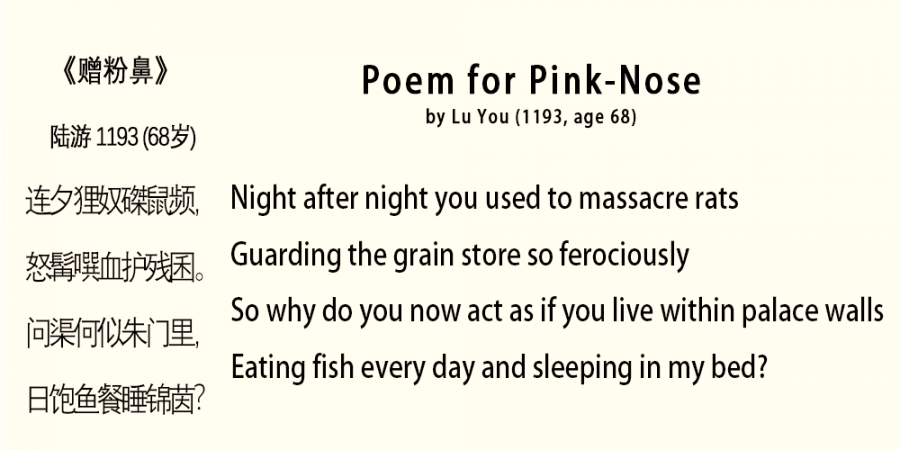

Or at least they do at first. “Night after night you used to massacre rats / Guarding the grain store so ferociously,” Lu asks one in “Poem for Pink-Nose.” “So why do you now act as if you live within palace walls / Eating fish every day and sleeping in my bed?”

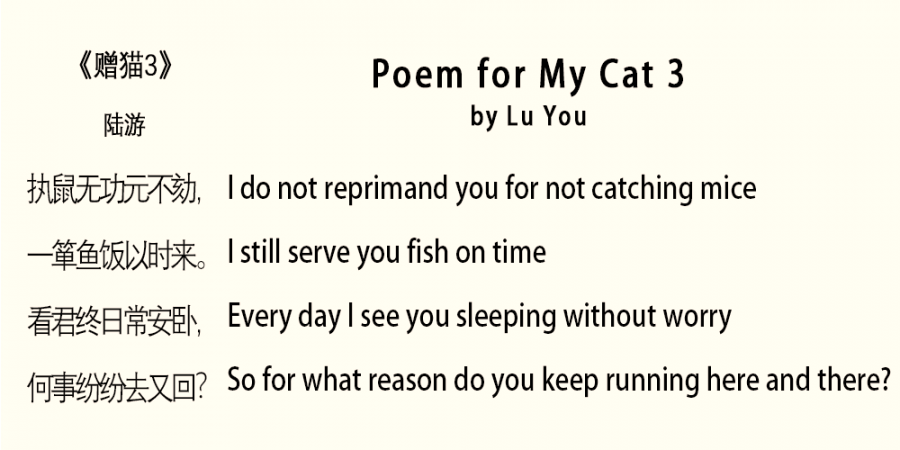

As time goes on, Lu finds himself “serving fish on time” to his cats only to find them “sleeping without worry.” As the rats rampage, he poetically moans, “my books are getting ruined and the birds wake me before dawn.” Has it all been nothing more than “a ruse to get food from me?”

Yet it seems that Lu has no regrets about cat ownership, if ownership be the word. “Wind sweeps the world and rain darkens the village / Rumbles roll off the mountains like ocean waves churning,” he writes in 1192’s “A Rainstorm on the Fourth Day of the Eleventh Month.” Yet “the furnace is soothing and the rug is warm / Me and my cat are not leaving the house.” This is relatable content for the cat butlers of Korea (a culture thoroughly influenced by China in Lu’s day), or indeed anywhere else in the world. The patriotic poet would surely be pleased by the modern-day ascent of China — and perhaps just as much by the high and ever-rising status of the domestic cat.

Related Content:

T.S. Eliot Reads Old Possum’s Book of Practical Cats & Other Classic Poems (75 Minutes, 1955)

Based in Seoul, Colin Marshall writes and broadcasts on cities, language, and culture. His projects include the book The Stateless City: a Walk through 21st-Century Los Angeles and the video series The City in Cinema. Follow him on Twitter at @colinmarshall, on Facebook, or on Instagram.

I smile, knowing that a wise man across the world and across time can be as attached to and watchful of his companion cat as I have always been of my own.

bootiful

I think that in “Poem for my Cat 3” he is saying that the cat will be fed by him whether he catches mice or not and yet the cat still hunts mice like its going to be his only meal. He is just marveling at how well his cat does his rat hunting job and how enthusiastically he does it even though its not like he needs to eat the rats to survive. The important part to note is that the owner was stating that they don’t starve their cat to make it hunt the rats and yet impressively the cat is always on the hunt. 😁