Kings of camp Alice Cooper and Salvador Dalí made a natural pair when they met in New York City in April of 1973. “A mind-melding of sorts took place,” writes Super Rad Now. “Over the course of about two weeks” Cooper and Dalí “ate together, drank together, and basked in the glow of each other’s exceptional uniqueness.” Then Dalí decided to turn Cooper into a hologram, the First Cylindric Chromo-Hologram Portrait of Alice Cooper’s Brain.

How did this come about? It was only a matter of time before Dalí sought out the “godfather of shock rock.” The Surrealist prankster “knew how to promote himself and others,” notes historian and writer Sophia Deboick in a fantastic understatement. Dalí had been shocking audiences decades before Vincent Furnier, lead singer of the band Alice Cooper—who took the name for himself in 1975—was born, making transgressive films like Un Chien Andalou and getting tossed out of the Surrealists for possible fascist sympathies and unabashedly commercial aspirations.

Dalí used his connections to the world of pop music to meet “figures such as Brian Jones, Bryan Ferry and David Bowie” in the late 60s and early 70s. He came calling at Cooper’s door after the 1972 “rapier-waving performance of ‘School’s Out’ on Top of the Pops [drew] the opprobrium of Mary Whitehouse… and a truck carrying a billboard image of Alice wearing only a snake… mysteriously ‘broke down’ on Oxford Circus the same summer, causing chaos.”

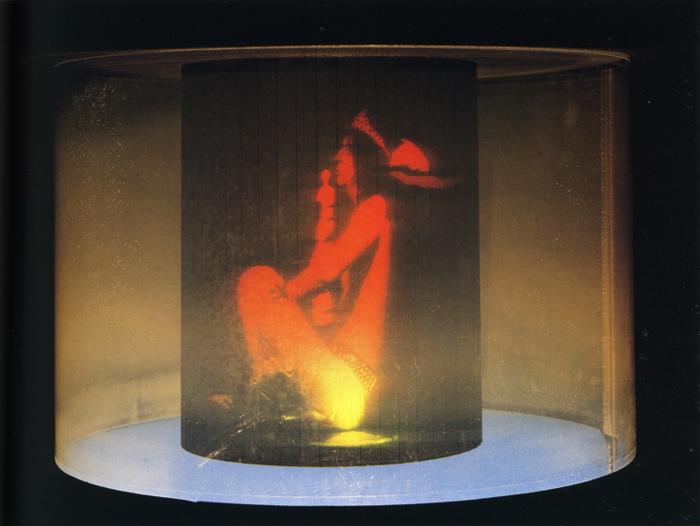

Cooper’s schtick was catnip to Dalí, but as usual, the artist had something more sophisticated in mind when he staged what looked like a typically bizarre publicity stunt. Cooper was invited to Dalí’s studio to pose with “an ant-covered plaster brain topped with a chocolate éclair.” This Dalí placed behind Cooper’s head on a red velvet cushion as Alice “sat on a rotating turntable wearing over a million dollars-worth of diamonds from the famous Harry Winston jewelers on Fifth Avenue (Cooper remembers it in the short video clip at the top as 4 million dollars worth), holding a fragmented Venus de Milo as a microphone.”

For Cooper and the band, the collaboration helped bring their own particular artistic vision to fruition, lending them the imprimatur of the most popular shock artist of the century. “Five of the original band members were art majors,” he later recalled, “and we worshipped Dalí: we thought of ourselves as surrealists.” (He also named one of his boa constrictors Dalí.)

For Dalí, the resulting holographic image fulfilled a longstanding exploration of new ideas and a new medium—as well as a deliberate movement away from his devotion to Freudian psychoanalysis.

Throughout the 1970s Dalí worked with optical illusions and stereoscopic images… but his interest in working in the third and fourth dimensions dated back further. His 1958 Anti-Matter Manifesto proclaimed his intent to abandon his exploration of the interior world for a focus on “the exterior world and that of physics [which] has transcended the one of psychology,” saying he had swapped Freud for Heisenberg. The tesseract cross of his Crucifixion (Corpus Hypercubus) (1954) was inspired by the diverse influences of mathematical theory, cubism, and works of Philip II’s architect Juan de Herrera and Catalan mystic Ramon Llull. The Alice hologram may have taken an emerging popular icon as its subject, but the medium was one which fulfilled Dalí’s artistic ambitions at the end of his career to embrace science and break out of the two dimensional.

The attention may have gone to Cooper’s head. He attended the unveiling of the hologram without his band members, then went on to record 1975’s Welcome to My Nightmare without them and promoted “an ABC television special starring Vincent Price” that same year, again with a new band. His star fell over the decade, but his essential place in rock and roll history had already been fully secured.

Alice Cooper’s (the band) gender-bending had influenced David Bowie and the New York Dolls. The Sex Pistol’s John Lydon breathlessly proclaimed them his favorite and sang (“or at least mimed to”) their “I’m Eighteen” at his audition. “The direct line between Alice Cooper and every possible genre of metal is obvious,” Deboick writes.

Like the Surrealist master, Cooper became something of a parody of his earlier incarnation in later years, and in sobriety, the preacher’s son from Detroit reappeared as a “golf-playing born-again Christian.” But however else he is remembered, the man born Vincent Furnier will also always be the only rock star to have his ant-covered brain turned into a hologram by Salvador Dalí, who knew a kindred spirit when he saw one. See a video of the hologram, which resides in Spain, just above.

Related Content:

Salvador Dalí & Walt Disney’s Short Animated Film, Destino, Set to the Music of Pink Floyd

Salvador Dalí Explains Why He Was a “Bad Painter” and Contributed “Nothing” to Art (1986)

Josh Jones is a writer and musician based in Durham, NC. Follow him at @jdmagness

The hologram of Dali and Alice Cooper isn’t in Spain. It’s in Saint Petersburg, FL at the Dali Museum.