“Great literature is one of two stories,” we often quote Leo Tolstoy as saying: “a man goes on a journey or a stranger comes to town.” That’s all well and good for the author of War and Peace, but what about the thousands of screenwriters struggling to come up with the next hit movie, the next hit television series, the next hit platform-specific web and/or mobile series? Some, of course, have found in that aphorism a fruitful starting point, but others opt for different premises that number the basic plots at three (William Foster-Harris), six (researchers at the University of Vermont’s Computational Story Lab), twenty (Ronald Tobias), 36 (George Polti) — or, as some struggling screenwriters of a century ago read, 37.

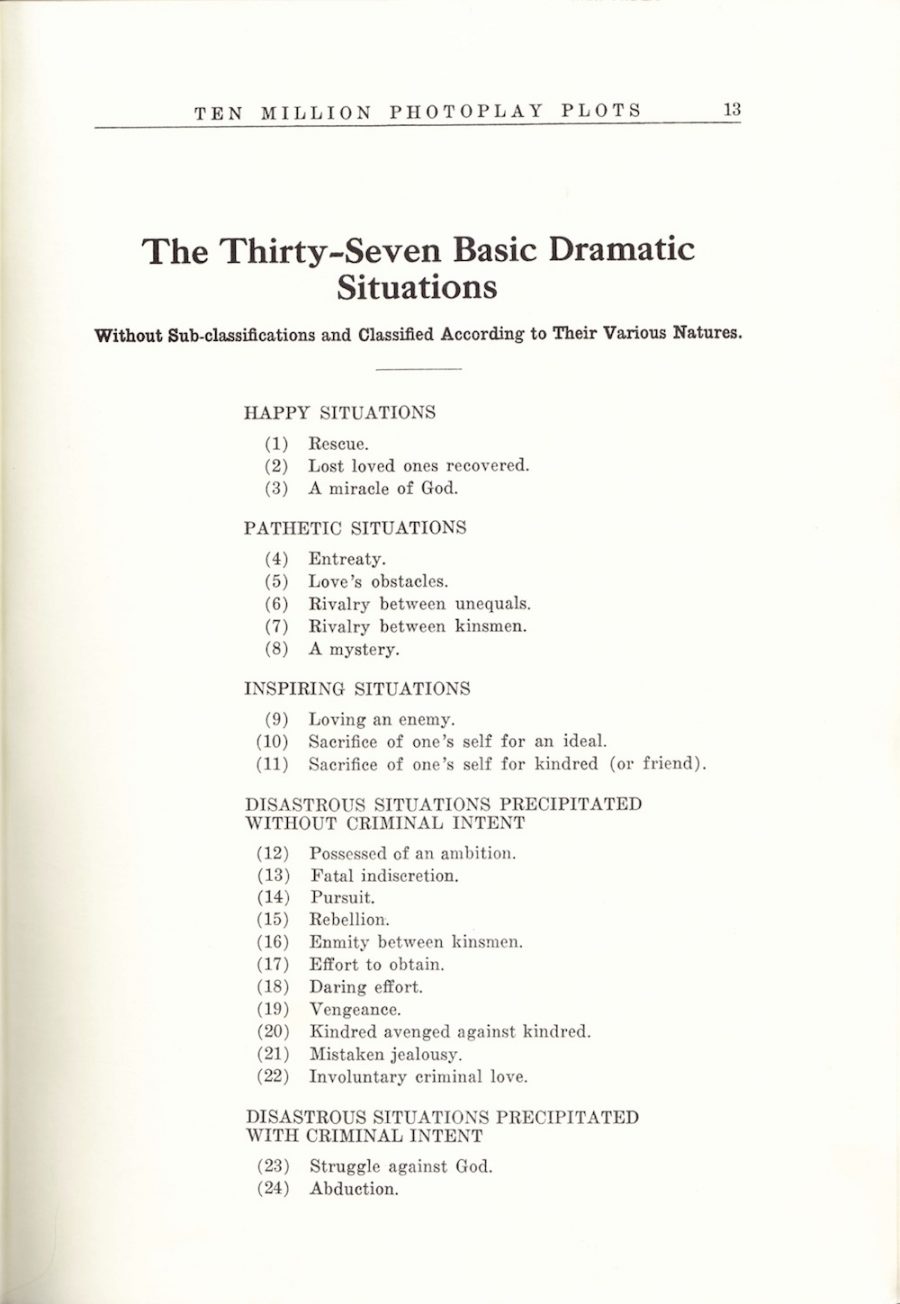

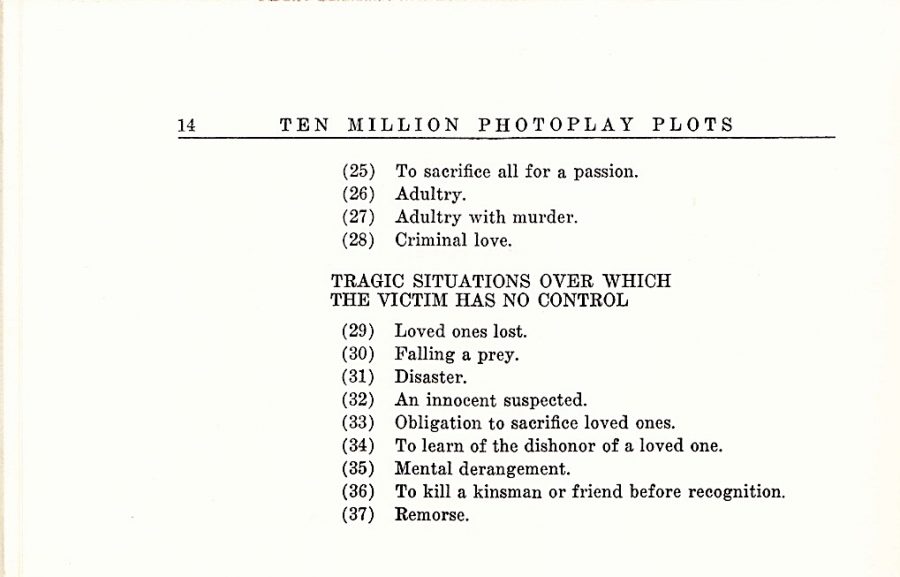

The year was 1919. America’s biggest blockbusters included D.W. Griffith’s Broken Blossoms, Cecil B. DeMille’s Male and Female, and The Miracle Man, which made Lon Chaney into a silver-screen icon. The many aspirants looking to write their way into the ever more celebrated and lucrative movie business could turn to a newly published manual called Ten Million Photoplay Plots by Wycliff Aber Hill. “Hill, who published more than one aid to struggling ‘scenarists,’ positioned himself as an authority on the types of stories that would work well onscreen,” writes Slate’s Rebecca Onion. In this book he provides a “taxonomy of possible types of dramatic ‘situations,’ first running them down in outline form, then describing each more completely and offering possible variations.”

Hill’s 37 basic dramatic situations include such “happy situations” as “rescue,” “loved ones lost and recovered,” and “a miracle of God”; such “pathetic situations” as “love’s obstacles,” “rivalry between unequals,” and “a mystery”; and such “disastrous situations precipitated without criminal intent” as “possessed of an ambition,” “enmity between kinsmen,” and “vengeance.” (Naturally, Hill also includes a separate category involving criminal intent.) These dramatic concepts then break down into more specific scenarios like “rescue by strangers who are grateful for favors given them by the unfortunate one,” “an appeal for refuge by the shipwrecked,” “the sacrifice of happiness for the sake of a loved one where the sacrifice is caused by unjust laws,” and “congenial relations between husband and wife made impossible by the parents-in-law.”

Already more than a few films new and old come to mind whose stories proceed from such dramatic concepts. Indeed, one could think of examples from not just cinema but literature, television, theater, comics, and other forms of narrative art besides. Situations we all know from real life may also follow similar contours, which plays no small part in giving them their impact when properly translated to the screen. Clearly aiming for timelessness, Hill enumerates plots that could have been employed in stories centuries before his time, and will continue to be long after ours. But what, exactly, is the relationship between plot and story? We now quote E.M. Forster on the matter, specifically a line from his Aspects of the Novel — a book for which Ten Million Photoplay Plots’ first readers would have to wait eight more years.

Related Content:

Kurt Vonnegut Diagrams the Shape of All Stories in a Master’s Thesis Rejected by U. Chicago

Raymond Chandler: There’s No Art of the Screenplay in Hollywood

Based in Seoul, Colin Marshall writes and broadcasts on cities, language, and culture. His projects include the book The Stateless City: a Walk through 21st-Century Los Angeles and the video series The City in Cinema. Follow him on Twitter at @colinmarshall, on Facebook, or on Instagram.

I think that’s been missunderstood. 37 are the situations, the stories are the many possible combinations of that 37 scenaries, this is, millions of possible stories. That’s how I understood that, in fact the title says clearly: “10 million photoplay plots”, and even this, I doubt about there are only 37 scenaries. In a century the humanity evolved a lot, discoverded thousands things and invented other thousand, so that number has increased for sure. Greetings.

There are only 3 possible stories in the world:

‑man vs man

‑man vs nature

‑man vs himself

Every story in the world is one of these or a combination of them.

Where do women fit in?

The Lion King fits in number 10: Inspiring Situations — Sacrifice of one’s self for an ideal.

Man V. AI.

This is the next frontier.

“Mankind” includes women… Don’t be pedantic now.