It’s odd to think that the gray-faced, gray-suited U.S. Cold Warriors of the 1950s funded Abstract Expressionism and left-wing literary magazines in a cultural offensive against the Soviet Union. And yet they did. This seeming historical irony is compounded by the fact that so many of the artists enlisted (mostly unwittingly) in the cultural Cold War might not have had careers were it not for the New Deal programs of 20 years earlier, denounced by Republicans at the time as communist.

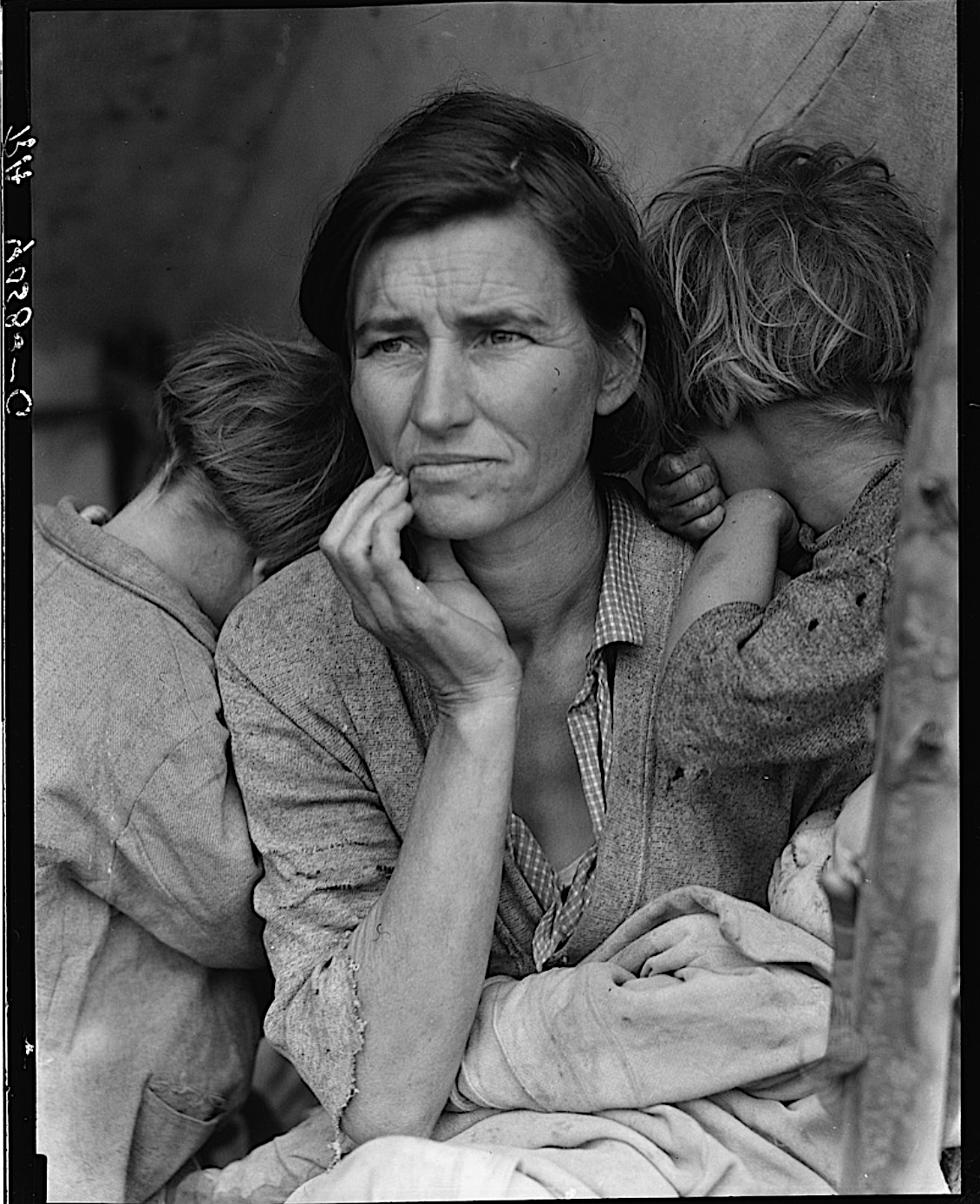

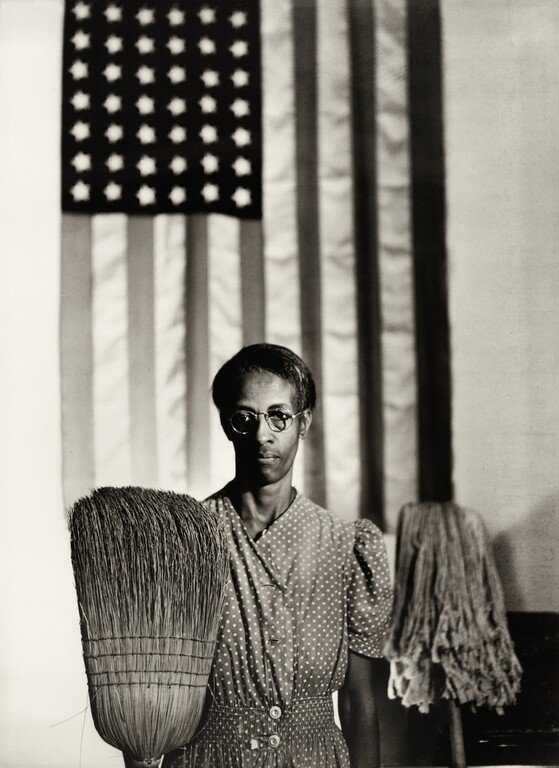

The New Deal faced fierce opposition, and its passage involved some very unfortunate compromises. But for artists, it was a major boon. Programs established under the Works Progress Administration in 1935 helped thousands of artists survive until they could get back to plying trades, working as professionals, or building world-famous careers. Artists and art workers once supported by the WPA include Dorothea Lange, Langston Hughes, Orson Welles, Ralph Ellison, Zora Neale Hurston, Gordon Parks, Alan Lomax, Mark Rothko, Jackson Pollock, James Agee, and dozens more famous names.

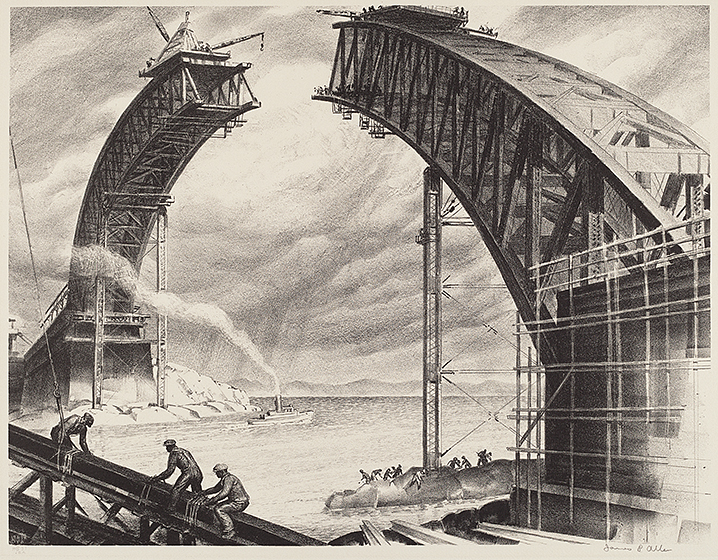

There were also thousands of unknown painters, photographers, sculptors, poets, dancers, playwrights, etc. who received funding in their local areas to put their skills to work. “Through the WPA,” the National Gallery of Art writes, artists “participated in government employment programs in every state and county in the nation.” As to the question of whether their work deserved to be paid, “Harry Hopkins,” Jerry Adler writes at Smithsonian, “whom President Franklin D. Roosevelt put in charge of work relief, settled the matter, saying, ‘”Hell, they’ve got to eat just like other people!”

He turns the question about who “deserves” relief on its head. Dance may not be necessary by some people’s lights but eating most certainly is. Why shouldn’t artists use their talent to beautify the country, collect and archive its cultural history, and provide quality entertainment in uncertain times? And why shouldn’t the country’s artists document the enormous building projects underway, and the major shifts happening in people’s lives, for posterity?

Roosevelt, taking many of his cues from Eleanor, spoke of funding the arts in much grander terms than the pragmatic Hopkins. He elaborated on his belief in their “essential” nature in a speech at the dedication of the Metropolitan Museum of Art’s new building in 1939:

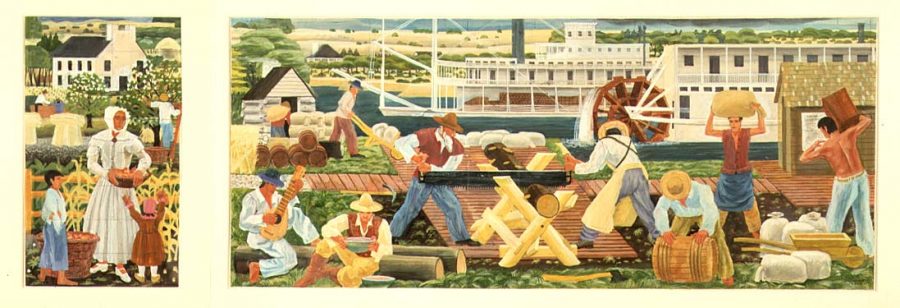

Art in America has always belonged to the people and has never been the property of an academy or a class. The great Treasury projects, through which our public buildings are being decorated, are an excellent example of the continuity of this tradition. The Federal Art Project of the Works Progress Administration is a practical relief project which also emphasizes the best tradition of the democratic spirit. The W.P.A. artist, in rendering his own impression of things, speaks also for the spirit of his fellow countrymen everywhere. I think the W.P.A. artist exemplifies with great force the essential place which the arts have in a democratic society such as ours.

In the future we must seek more widespread popular understanding and appreciation of the arts. Many of our great cities provide the facilities for such appreciation. But we all know that because of their lack of size and riches the smaller communities are in most cases denied this opportunity. That is why I give special emphasis to the need of giving these smaller communities the visual chance to get to know modern art.

As in our democracy we enjoy the right to believe in different religious creeds or in none, so can American artists express themselves with complete freedom from the strictures of dead artistic tradition or political ideology. While American artists have discovered a new obligation to the society in which they live, they have no compulsion to be limited in method or manner of expression.

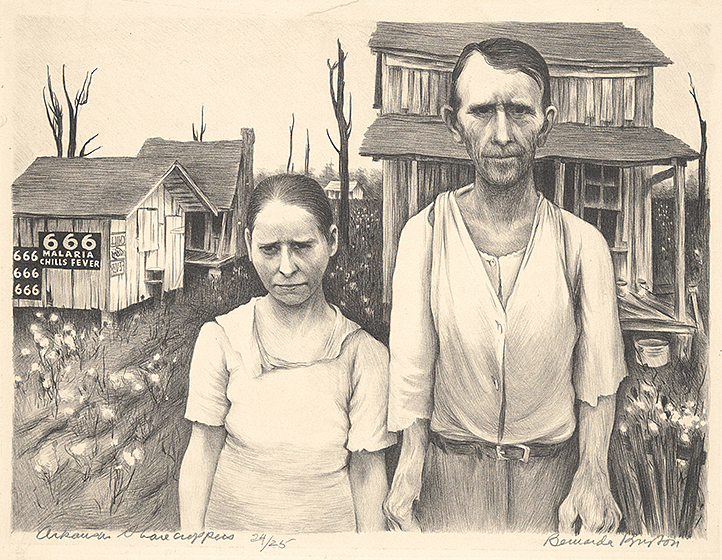

He began the address with several airy phrases about freedom and liberty; here, he defines what that looks like for the artist—the ability to have dignified work and livelihood, and to operate with full creative freedom. Of course, artists, especially those employed in decorating public buildings, were constrained by certain “American” themes. But they could interpret those themes broadly, and they did, picturing scenes of hardship and leisure, recovering the past and imagining better futures.

It couldn’t last. “The WPA-era art programs reflected a trend toward the democratization of the arts in the United States and a striving to develop a uniquely American and broadly inclusive cultural life,” the National Gallery explains. Art from this period “offers a window through which to explore the social conditions of the Depression, the mainstreaming of art and birth of ‘public art,’ and the opening of government employment to women and African Americans.” Opponents of the programs pushed back with red baiting. Arts funding under the WPA was ended in 1943 by a Congress, says scholar of the period Francis O’Connor, who could “look at two blades of grass and see a hammer and sickle.”

See much more New Deal art–including plays, photography, art posters and more–at the National Gallery of Art, the National Archives, Smithsonian, and at the links below.

Related Content:

Yale Presents an Archive of 170,000 Photographs Documenting the Great Depression

Josh Jones is a writer and musician based in Washington, DC. Follow him @jdmagness

There needs to be a follow-up to this article and it needs to be titled “The Art of CETA: Why the Federal Government Funded the Arts During the 1970s Recession.”

The Comprehensive Employment and Training Act (CETA) was responsible for the largest federally funded arts initiative outside of the WPA, employing more than 20,000 artists and arts support staff nationally during the period 1974–1981. At its peak, in 1980, the program funneled between $200 and $300 million (about a billion in in 2021 dollars) into the arts. In comparison, the National Endowment for the Arts budget that year was only $159 million. Yet, CETA’s projects are virtually unknown.

CETA was bi-partisan, signed into law by Richard Nixon and expanded under Jimmy Carter’s administration. CETA especially benefited women artists and artists of color.

Artists and art workers once supported by CETA include Dawoud Bey, Willie Birch, Ellsworth Ausby, Ademola Olugebefola, Judy Baca, Ursula von Rydingsvard, Christy Rupp, Willie Cole, Senga Nengudi, Maren Hassinger and Fred Wilson; poet Norman Pritchard and musician Julius Eastman; members of the Alvin Ailey dance company; the Black Theater Alliance; La Mama E.T.C.; the Afro-Latin Band and Jazzmobile; playwright August Wilson; and with entities like the Woman’s Building and Brockman Gallery (LA), the Penumbra Theater (St. Paul), and Brandywine Workshop and Philadanco (both Philadelphia).

The exhibition ART / WORK documents the Cultural Council Foundation CETA Artists Project in NYC, and is on display at City Lore and Cuchifritos Gallery on the Lower East Side through March. Go to for more information.

The WPA programs of the 1930s are an excellent example of crucial government support for artists in a time of need. A similar program that took place during the 1970s and was almost as large has almost been forgotten by history. The Comprehensive Employment and Training Act (CETA) employed 10,000 artists in all fields and 10,000 arts support professionals during the period 1973–81. Unlike the WPA, it was decentralized and did not benefit from an organized national propaganda effort. Additionally, it focused on putting artists into community service — although many murals and other public works were created. Importantly, in terms of providing a potential model for the current cultural crisis, it had bipartisan support! For more, see .

Great article and photos/art!

and Blaise — I agree! The art programs in CETA (including the one in NYC, with over 300 artists, the largest Federal arts project since the WPA, in which I participated), is an even better, and more recent, model.

Cheers for the WPA, and CETA too, and let’s put artists back to work now! Culture is a basic human right.

An archive of the New York City CETA Artists Project can be found at:

https://ceta-arts.com/

As a young photographer it was a life-changing experience for me.

and Bob — I agree! Without culture.…..?

This article could have been written today about the Comprehensive Training and Employment Act of 1972, or CETA as it is most widely known.

The Works Project Administration (WPA) and CETA are two excellent examples of looking back to historic public policy to elevate the prospect of employment for artists through the government. Particularly in times of economic crisis, this public policy approach has worked well, as during the 1970’s when unemployment levels were registered in double digits and many of those unemployed had college degrees. I managed the programs at that time in my city, and I know this approach worked for many artists that went on to be prominent in their fields of choice, much like those mentioned in this article. Some of the many noted artists of that era in Minnesota include August Wilson, Claude Purdy, Marion McClinton, and all of the Penumbra theatre alumnae, as well as original members of the Prairie Home Companion company. Other examples abound.