Having watched the development of interactive data visualizations as a writer for Open Culture, I’ve seen my share of impressive examples, especially when it comes to mapping music. Perhaps the oldest such resource, the still-updating Ishkur’s Guide to Electronic Music, also happens to be one of the best for its comprehensiveness and witty tone. Another high achiever, The Universe of Miles Davis, released on what would have been Davis’ 90th birthday, is more focused but no less dense a collection of names, record labels, styles, etc.

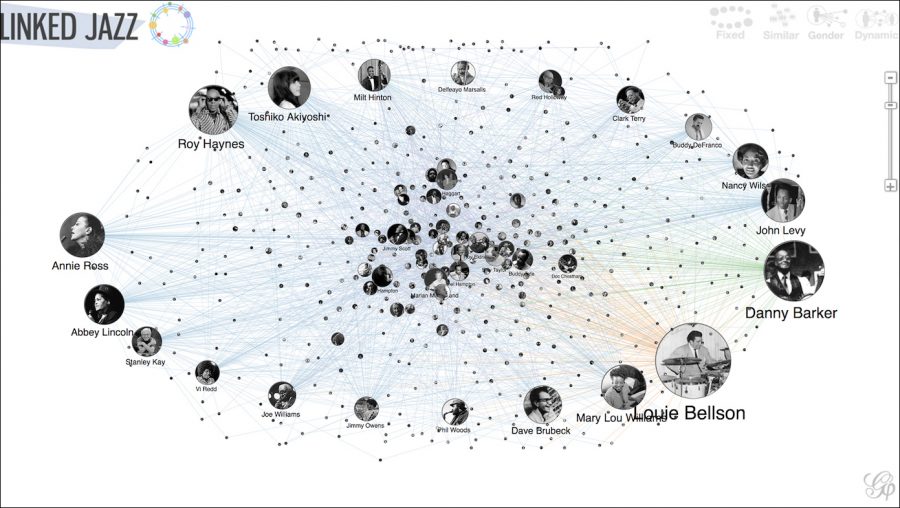

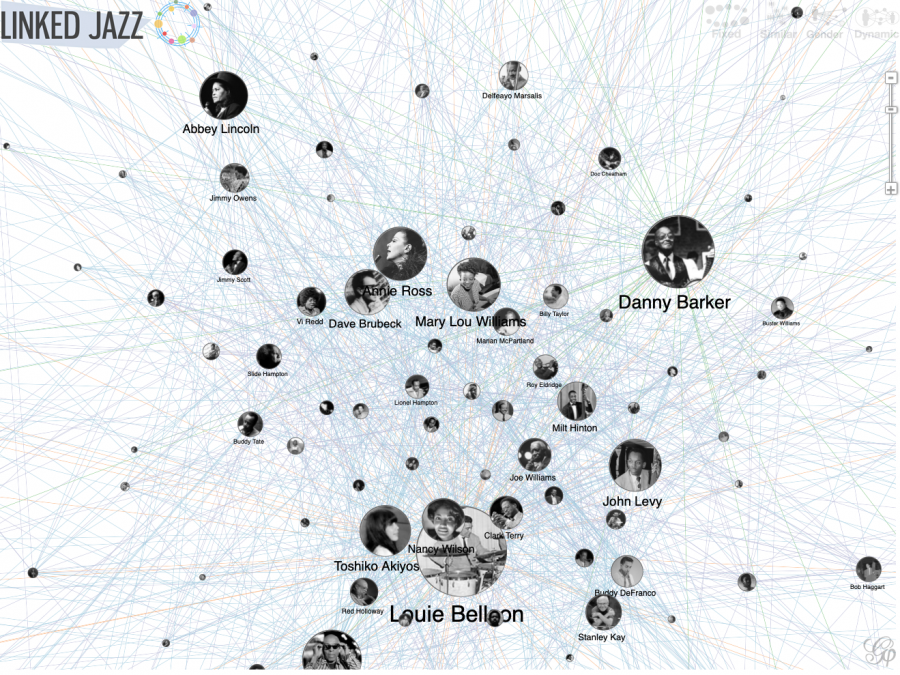

While visualizing the history of any form of music can result in a significant degree of complexity, depending on how deeply one drills down on the specifics, jazz might seem especially challenging. Choosing one major figure pulls up thousands of connections. As these multiply, they might run into the millions. But somehow, one of the best music data visualizations I’ve seen yet—Pratt Institute’s Linked Jazz project—accounts seamlessly for what appears to be the whole of jazz, including obscure and forgotten figures and interactive, dynamic filters that make the history of women in jazz more visible, and let users build maps of their own.

Jazz musicians “are like family,” Zena Latto, one of the musicians the project recovered, told an interviewer in 2015. A multi-racial, transnational, actively multi-generational family that meets all over the world to play together constantly, that is. As a form of music built on ensemble players and journeymen soloists who sometimes form bands for no more than a single album or tour, jazz musicians probably form more relationships across age, gender, race, and nationality than those in any other genre.

That organic, built-in diversity, a feature of the music throughout its history, shows up in every permutation of the Linked Jazz map, and comes through in the recorded interviews, performances, and other accompanying info linked to each musician. Like the Universe of Miles Davis, Linked Jazz leans heavily on Wikipedia for its information. And in using such “linked open data (LOD),” as Pratt notes in a blog post, the project “also reveals archival gaps. While icons such as John Coltrane and Miles Davis have large digital footprints, lesser-known performers may barely have a mention”—despite the fact that most of those players, at one time or another, played with, studied under, or recorded with the greats.

Such was the case with Latto, who was mentored by Benny Goodman and toured throughout the 1940s and 50s with the International Sweethearts of Rhythm, “considered the first integrated all-women band in the United States.” Latto was “part of a network that stretched from New York to New Orleans,” but her name had disappeared entirely until Pratt School of Information professor Cristina Pattuelli found it on a tattered flyer for a Carnegie Hall concert. “Soon, through Linked Jazz, Lotta had a Wikipedia page and her interview was published on the Internet Archive.”

Linked Jazz’s focus on women musicians does not mean gender segregation, but a rediscovery of women’s place in all of jazz. Like all of the other filters, the Linked Jazz data map’s gender view shows both men and women prominently in the little photo bubbles connected by webs of red and blue lines. But as you begin clicking around, you will see the perspective has shifted. “Linked Jazz has concentrated on processing more interviews with women jazz musicians,” writes Pratt, “and these resources have been enhanced by a series of Women of Jazz Wikipedia Edit-a-thons in 2015 and 2017.”

Likewise, the inclusion of these interviews, biographies, and recordings have enhanced the breadth and scope of Linked Jazz, which as a whole represents the best intentions in open data mapping, realized by a design that makes exploring the daunting history of jazz a matter of strolling through a digital library with the entire catalog appearing instantly at your fingertips. The project also shows how thoughtful data mapping can not only replicate the existing state of information, but also contribute significantly by finding and restoring missing links.

via

Related Content:

The Influence of Miles Davis Revealed with Data Visualization: For His 90th Birthday Today

How Dave Brubeck’s Time Out Changed Jazz Music

The Brains of Jazz and Classical Musicians Work Differently, New Research Shows

Josh Jones is a writer and musician based in Durham, NC. Follow him at @jdmagness

Leave a Reply