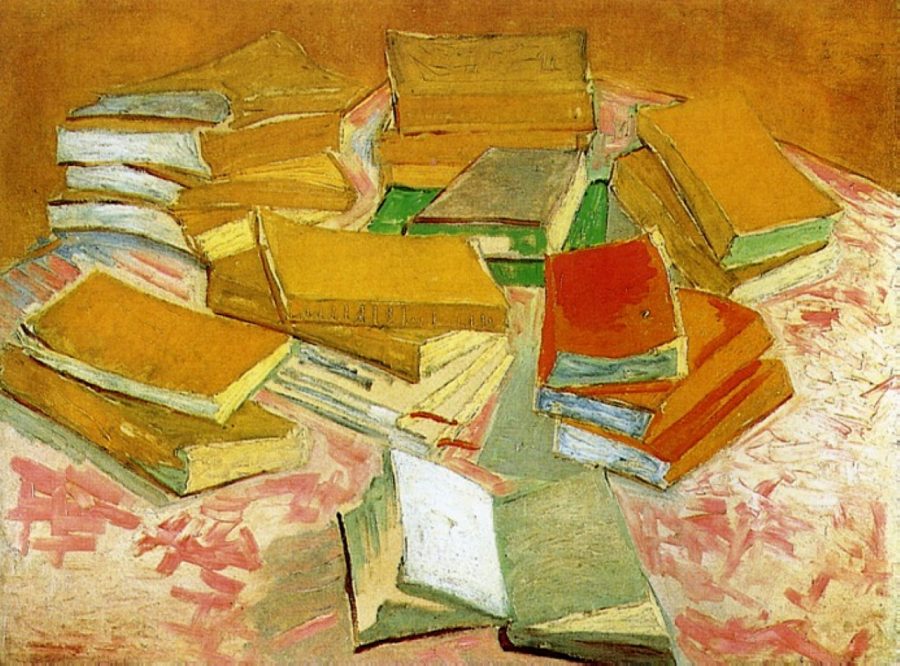

Piles of French Novels, Vincent Van Gogh, 1887

Among lovers of Vincent van Gogh, the Dutch artist is as well known for his letter writing as for his extraordinary painting. “The personal tone, evocative style and lively language” of his correspondence, writes the Van Gogh Museum, “prompted some people who were in a position to know to accord the correspondence the status of literature. The poet W.H. Auden, who published an anthology with a brief introduction, wrote: ‘there is scarcely one letter by Van Gogh which I, who am certainly no expert, do not find fascinating.’”

Auden was, of course, an expert on the written word, though maybe not on Van Gogh, and he refined his literary expertise the same way the painter did: by reading as copiously as he wrote. “When it was too dark to paint,” writes University of Puerto Rico professor of humanities Jeffrey Herlihy Mera at the Chronicle of Higher Education, “Van Gogh read prodigiously and compiled a tremendous amount of personal correspondence.” Much of his writing, especially his letters to his brother Theo, was in French, a language he learned in his teens and spoke in Belgium, Paris, and Arles.

Van Gogh’s command of written French, however, came from his reading of Victor Hugo, Guy de Maupassant, and Émile Zola. “Vincent loved literature,” the Van Gogh Museum writes. “In general, the books he read reflected what was going on in his own life. When he wanted to follow in his father’s footsteps and become a minister, he read books of a religious nature. He devoured Parisian novels when he was considering moving to the French capital.”

In his letters to Theo, he weaves together the sacred and profane, describing his spiritual and creative strivings and his unrequited obsessions. In his reading, he tested his values and desires. We get a sense of how Van Gogh’s reading complemented his pious, yet romantic nature in the list of some of his favorites, below, compiled by the Van Gogh Museum.

- Charles Dickens, A Christmas Carol (1843)

- Jules Michelet, L’amour (1858)

- Émile Zola, L’Oeuvre (1886)

- Alphonse Daudet, Tartarin de Tarascon (1887)

- The Bible

- John Keats, The Eve of St. Agnes (1820)

- George Eliot, Scenes of Clerical Life (1857)

- Henry Wadsworth Longfellow, The Poetical Works of Henry Wadsworth Longfellow (1887)

- Hans Christian Andersen, What the Moon Saw (1862)

- Thomas a Kempis, The Imitation of Christ (1471–1472)

- Harriet Beecher Stowe, Uncle Tom’s Cabin (1851–1852)

- Edmond de Goncourt, Chérie (1884)

- Victor Hugo, Les misérables (1862)

- Honoré de Balzac, Le Père Goriot (1835)

- Guy de Maupassant, Bel-Ami (1885)

- Pierre Loti, Madame Chrysanthème (1888)

- Voltaire, Candide (1759)

- Shakespeare, Macbeth (c. 1606–1607)

- Shakespeare, King Lear (1606–1607)

- Charles Dickens, Hard Times (1854)

- Emile Zola, Nana (1880)

- Emile Zola, La joie de vivre (1884)

“Vincent read moralistic books often favoured among members of the Protestant Christian community” in which he was raised by his minister father. He looked also to the morality of Charles Dickens, whose works he “read and reread… throughout his life.” Zola’s “rough, direct naturalism” appealed to Van Gogh’s desire “to give an honest depiction of what he saw around him: farm labourers, a weathered little old man, dejected or working women, a soup kitchen, a tree, dunes and fields.”

In Alphonse Daudet’s 1887 Tartarin de Tarascon, “an entertaining caricature of the southern Frenchman,” Van Gogh satisfied his “need for humor and satire.” Despite the stereotype of the artist as perpetually tortured, his letters consistently reveal his good-natured sense of humor. From French historian Jules Michelet’s 1858 L’amour, the artist “found wisdom he could apply to his own love life,” tumultuous as it was. He used Michelet’s insights “to justify his choices,” such as “when he fell in love with his cousin Kee Vos.”

In a letter to Theo, Vincent expressed his emotional struggles over Vos’s rejection of him as “a great many ‘petty miseries of human life,’ which, if they were written down in a book, could perhaps serve to amuse some people, though they can hardly be considered pleasant if one experiences them oneself.” He is at a loss for what to do with himself, he writes, but “‘wandering we find our way,’ and not by sitting still.” For Van Gogh, “wandering” just as often took the form of sitting still with a good book.

Related Content:

Download Hundreds of Van Gogh Paintings, Sketches & Letters in High Resolution

13 Van Gogh’s Paintings Painstakingly Brought to Life with 3D Animation & Visual Mapping

Josh Jones is a writer and musician based in Durham, NC. Follow him at @jdmagness

Leave a Reply