“I heard it as a sort of musical kaleidoscope of America, of our vast melting pot, of our unduplicated national pep, of our blues, our metropolitan madness.” So said Porgy and Bess composer George Gershwin of Rhapsody in Blue, the orchestral piece he wrote back in 1924 and which has remained in the American canon ever since. It will surely become even more widely heard from this year on, since 1924 plus 95 — the term of a copyright under current United States law — equals 2020. Given that Rhapsody in Blue’s entrance into the public domain means that creators can now freely do what they like with it, the piece will also, no doubt, undergo all manner of creative rearrangement and repurposing in order to reflect the America of the 2020s.

Copyright terms didn’t always last nearly a century. Before the 1998 Copyright Term Extension Act they lasted only 75 years, and for the additional two decades of waiting for works to enter the public domain we usually blame Disney. That entertainment giant did indeed do much of the lobbying for copyright extension, seeking to retain its rights to Mickey Mouse’s 1928 debut Steamboat Willie.

But as Duke Law’s Center for the Study of the Public Domain reports in a post on the works newly in public domain this year, “the Gershwin Family Trust also pushed for the extension, so that George and Ira Gershwin’s works from the 1920s and 1930s would remain under copyright.” But now several been liberated from it: not just Rhapsody in Blue, but also standards (with lyrics penned by Gershwin’s brother Ira) like “Fascinating Rhythm” and “Oh, Lady Be Good!”

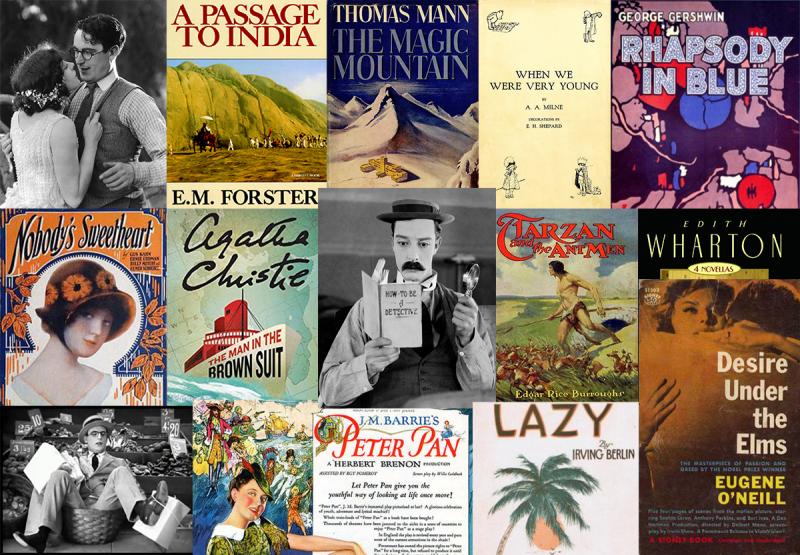

2020’s is a promising Public Domain Day indeed for fans of the Great American Songbook, what with the work of other composers like Irving Berlin (specifically the popular tune “Lazy,” well known from Marilyn Monroe’s performance in There’s No Business Like Show Business.) But the list of literary works that have just gone public-domain is even more impressive, boasting internationally acclaimed books like Thomas Mann’s The Magic Mountain, E.M. Forster’s A Passage to India, Edith Wharton’s novella collection Old New York, and the pillar of modern dystopian literature that is Yevgeny Zamyatin’s We (in English translation by Gregory Zilboorg). In many works of 1924, we can see the roots of the art we make and enjoy in 2020.

That holds especially true in the realm of film, which this year contributes to the public domain pictures from two masters of silent comedy: Harold Lloyd’s Girl Shy and Hot Water, and Buster Keaton’s The Navigator and Sherlock, Jr. That last film has the honor of being preserved by the United States Library of Congress for its cultural significance, as well as of having been named by the American Film Institute one of the funniest motion pictures in American history. You can learn more about all that entered the public domain this year (and what might, but for changes in the law, have entered it) at the Center for the Study of the Public Domain and the Public Domain review. But even more important than what enters the increasingly kaleidoscopic melting pot of the public domain, of course, is what we do with it. Future George Gershwins, Thomas Manns, and Buster Keatons, take note.

Related Content:

Ella Fitzgerald Sings ‘Summertime’ by George Gershwin, Berlin 1968

Rare 1940 Audio: Thomas Mann Explains the Nazis’ Ulterior Motive for Spreading Anti-Semitism

Based in Seoul, Colin Marshall writes and broadcasts on cities, language, and culture. His projects include the book The Stateless City: a Walk through 21st-Century Los Angeles and the video series The City in Cinema. Follow him on Twitter at @colinmarshall or on Facebook.

Actually, 1924 + 95 = 2019. I know what you mean, but this makes the writer look like a fool. Should be rewritten.