As we approach three full decades of a world without the Soviet Union, certain details about life in the societies that constituted it inevitably begin to fade from living memory. But nobody who grew up Soviet could ever forget the children’s books they grew up reading, and recent efforts to digitally archive them — such as Playing Soviet at the Cotsen Collection at Princeton’s Firestone Library, previously featured here on Open Culture — have ensured that future generations will be able to enjoy them too, no matter the regime under which they come of age, or even what language they speak.

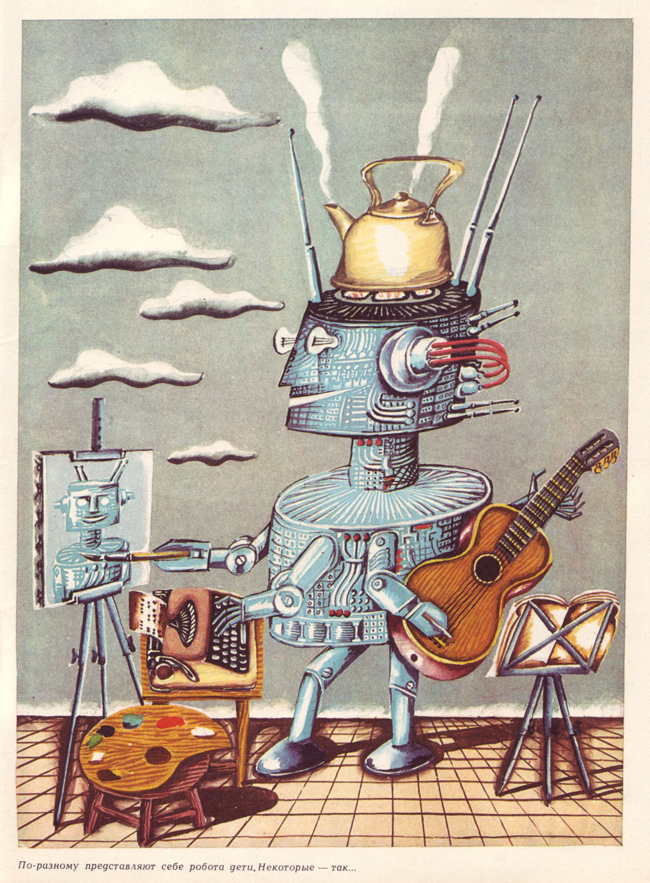

Most Soviet children’s books have such captivating illustrations that one need not read them to enjoy them. Take, for instance, Your Name? Robot, a 1979 Soviet picture book featured on book and design blog 50 Watts.

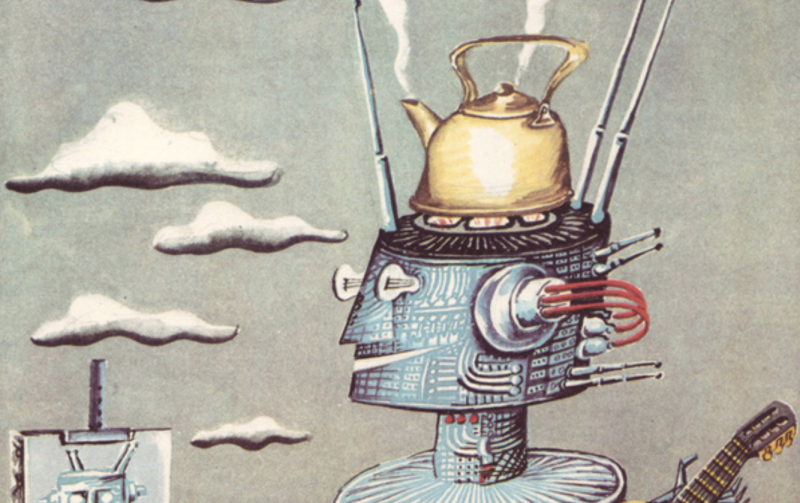

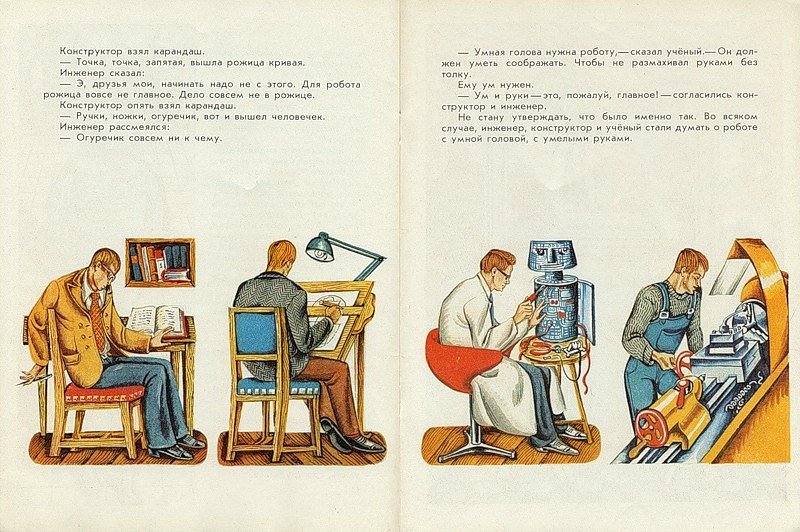

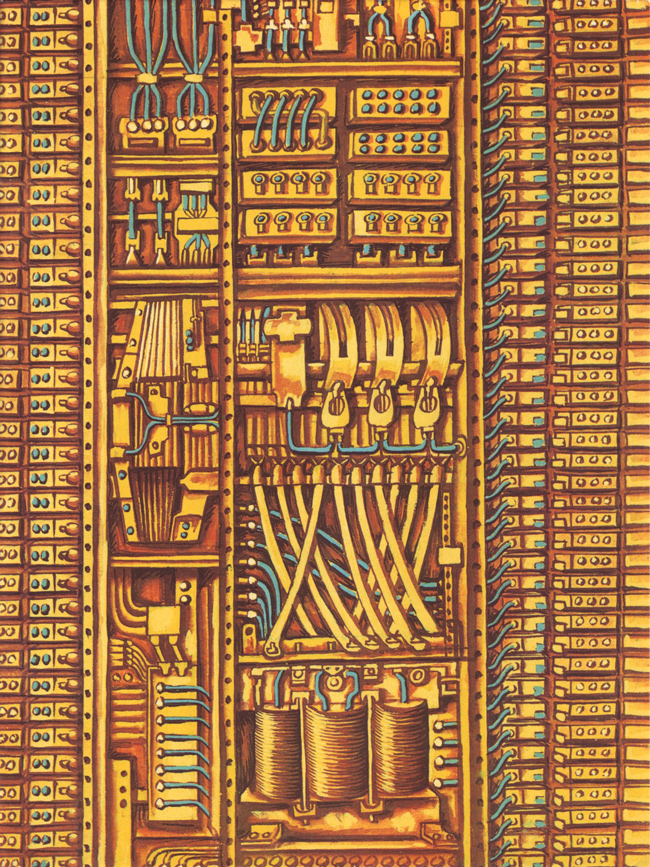

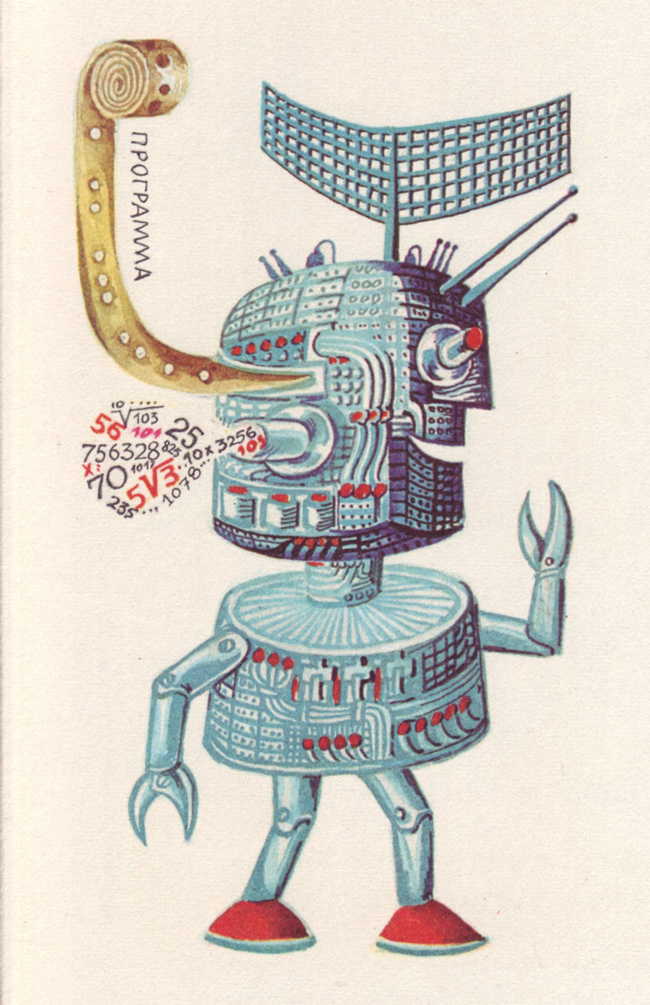

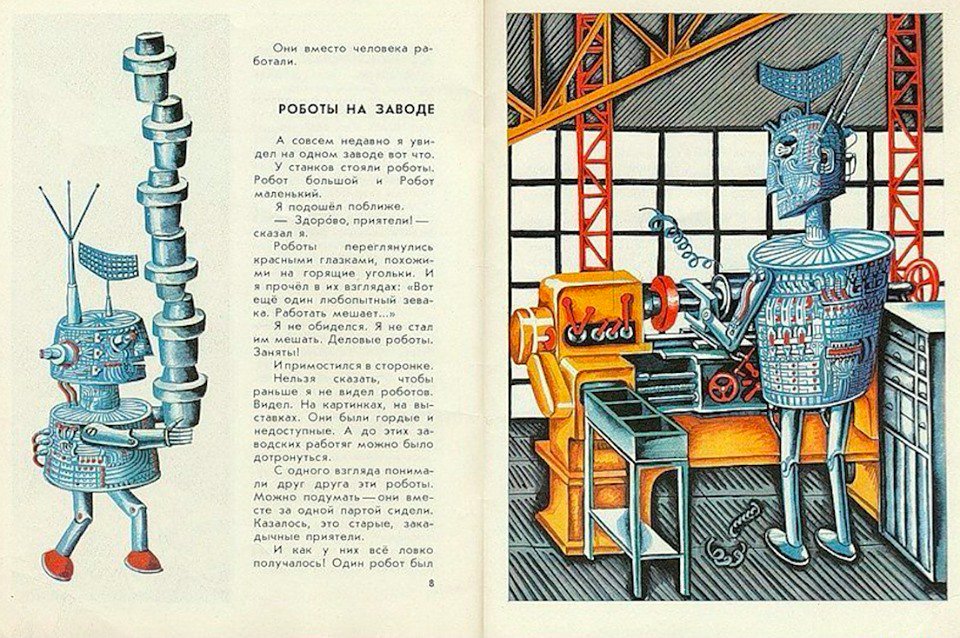

Who could resist the charm of these mechanical creatures displaying their many abilities: picking up signals, playing music, painting pictures, spouting complicated figures, boiling water? With their hypnotically detailed patterns of circuits and wires, the inner workings of these robots also look quite unlike anything else — and certainly unlike the also-popular robot characters who have long figured into stories for American children.

In the mid-20th century, America and the Soviet Union were racing each other to the future: though visionaries in both lands may have disagreed about what exact form that future would take, many saw some kind of utopia made real through high technology dead ahead. And whether worker’s paradise or consumer’s paradise, the rest of the millennium would surely see the development of intelligent robots to assist, educate, and entertain us.

But by the late 1970s, some of these visions had turned dystopian: to borrow the tagline from Zardoz, they’d seen the future, and it didn’t work — itself a grim reversal of American journalist Lincoln Steffens’ optimistic early-20th-century declaration about Soviet Russia.

From Soviet cinema, one less-than-optimistic treatment of the future endures above all: 1972’s Solaris, adapted by Andrei Tarkovsky from the novel by Stanislaw Lem. The production designer who gave that film’s future its look and feel was none other than Mikhail Romadin, the artist who would go on to illustrate Your Name? Robot just a few years later (in an illustration career involving hundreds of books, including volumes by Leo Tolstoy and Ray Bradbury).

“Romadin’s character is hidden, forced deep inside,” said Tarkovsky of his collaborator and friend since film school. “In his best works what often happens is that the outward characteristics of barely ordered dynamism and chaos that one perceives initially, melt imperceptibly into the appreciation of calm and noble form, silent and simple” — an appreciation Your Name? Robot must have done its part to instill in a generation of young readers.

Related Content:

Soviet-Era Illustrations Of J. R. R. Tolkien’s The Hobbit (1976)

Enter an Archive of 6,000 Historical Children’s Books, All Digitized and Free to Read Online

Based in Seoul, Colin Marshall writes and broadcasts on cities, language, and culture. His projects include the book The Stateless City: a Walk through 21st-Century Los Angeles and the video series The City in Cinema. Follow him on Twitter at @colinmarshall or on Facebook.

Leave a Reply