Critical theorists like Theodor Adorno may have overreached in claiming that all mass culture is mediocre, mechanized propaganda made to justify the status quo. But that doesn’t mean they were entirely wrong. Over and over we see even the most subversive art, literature, film, and music has a way of being tamed and Bowdlerized. Global mega-corporate industries don’t need to censor what they don’t like; they only need to buy it, rebrand it, or price it out of reach.

So what? Why do we need challenging, independent art when we have endless entertainment? Is the concept a nostalgic, elitist, Eurocentric idea? Artists have justified the need for art since antiquity, with poetic and logical arguments of every kind. But Dada artists of the early 20th century broke ranks, building their movement on the insight that no defense could possibly mean anything when it came to art’s purpose, especially in the face of the technocratic slaughter of World War I.

When the hyperrationalism of modernity led to mass death and destruction, the only humane response was to declare war on rationalization—to “destroy the hoaxes of reason,” as French artist Jean Arp put it. “For the disillusioned artists of the Dada movement,” the Museum of Modern Art explains, “the war merely confirmed the degradation of social structures that led to such violence: corrupt and nationalist politics, repressive social values, and unquestioning conformity of culture and thought.”

Dada took a combative stance against, for one thing, the insistence that art justify its existence to win establishment approval. “All activity is vain,” declared poet Tristan Tzara in his 1918 “Dada Manifesto,” including the “monetary system, pharmaceutical product, or a bare leg advertising the ardent sterile spring…. The beginnings of Dada were not the beginnings of art, but of disgust” with the ossified culture of the “nice, nice bourgeois,” who would preserve at any cost “the possibility of wallowing in cushions and good things to eat.”

“And so Dada,” wrote Tzara, “was born of a need for independence, of a distrust toward unity.” Such declarations aside, the movement was decidedly unified in its aims. “For us, art is not an end in itself,” poet Hugo Ball wrote. “It is an opportunity for the true perception and criticism of the times we live in.” This critique required new experimental techniques that deformed and repurposed the technologies of mass culture.

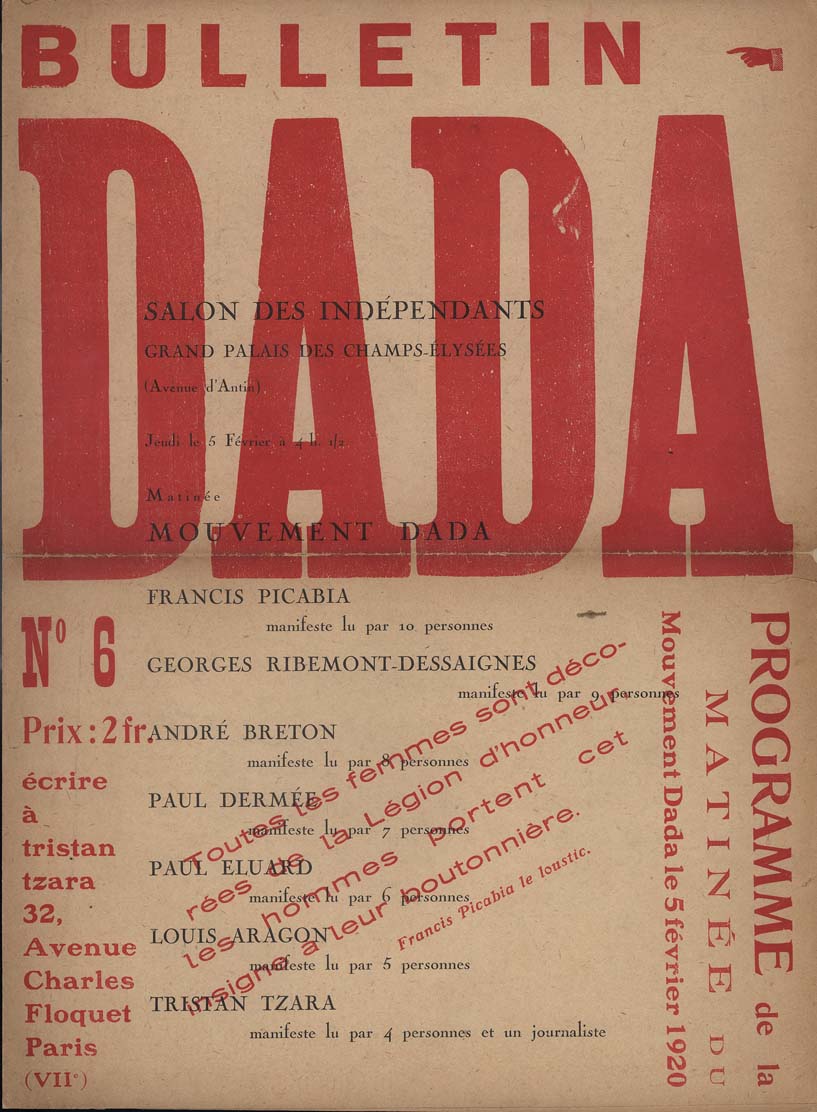

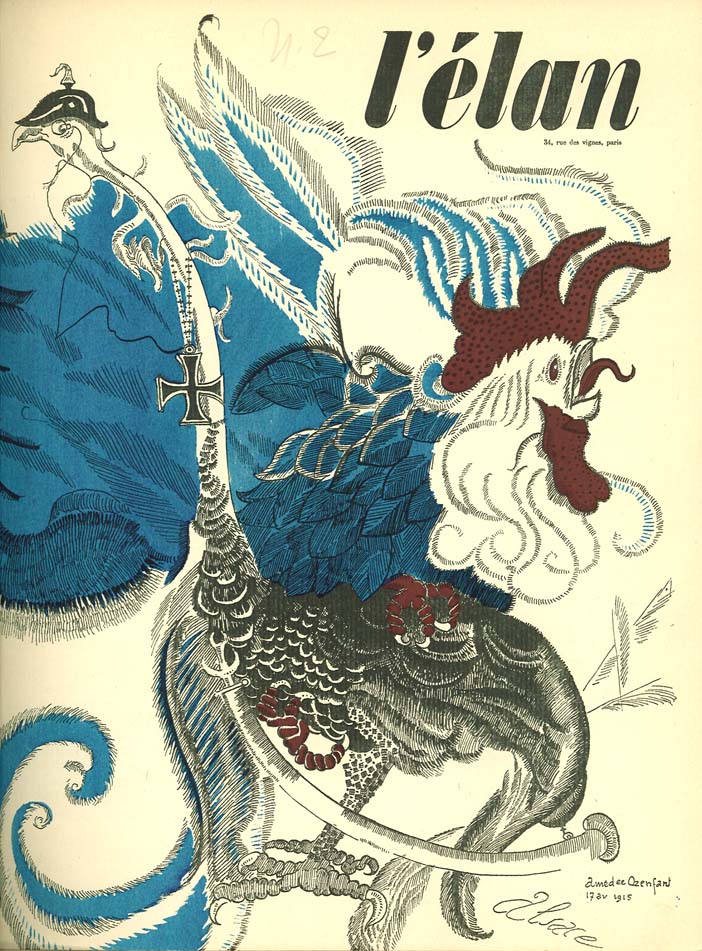

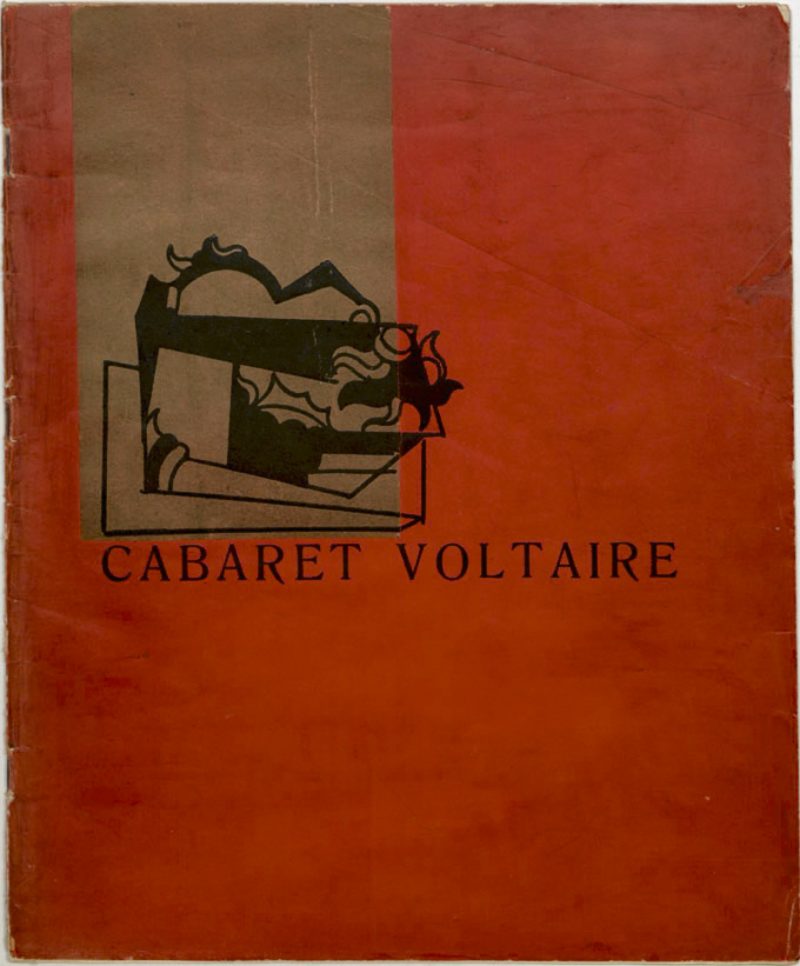

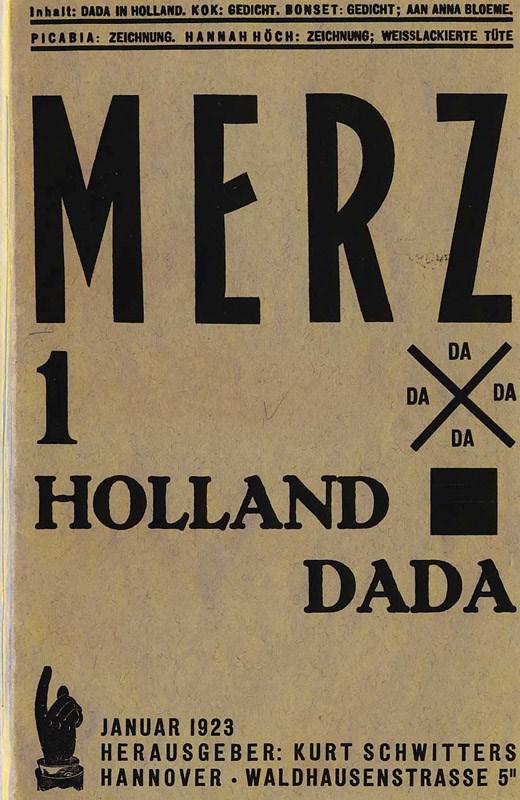

The undertaking would not have been possible without a Dada publishing wing that turned out scores of journals, magazines, books, leaflets, essays, manifestos, etc., written, designed, edited, illustrated, photographed, and controlled by the artists themselves. They might find no small amount of irony in the fact that their productions have received the ultimate institutional sanction: housed in “nice, nice bourgeois” museums, libraries, and universities around the world.

The University of Iowa’s International Dada Archive has amassed a considerable number of Dada publications and offers a wealth of high-quality scanned images of the originals on their site. “The first section” of their Digital Library “includes some of the major periodicals of the Dada movement from Zurich, Berlin, Paris, and elsewhere.” These are not always complete runs, though the library has included “reprints of issues for which we do not own originals” to make up for missing items in the collection.

The second section of the site “includes books by some of the participants in the Dada movement, as well as some of the more ephemeral Dada-era publications, such as exhibiton catalogs and broadsides.” You’ll find writings by all of the artists mentioned above, as well as other well-known names like Max Ernst, Paul Eluard, George Grosz, Man Ray, Francis Picabia, and more.

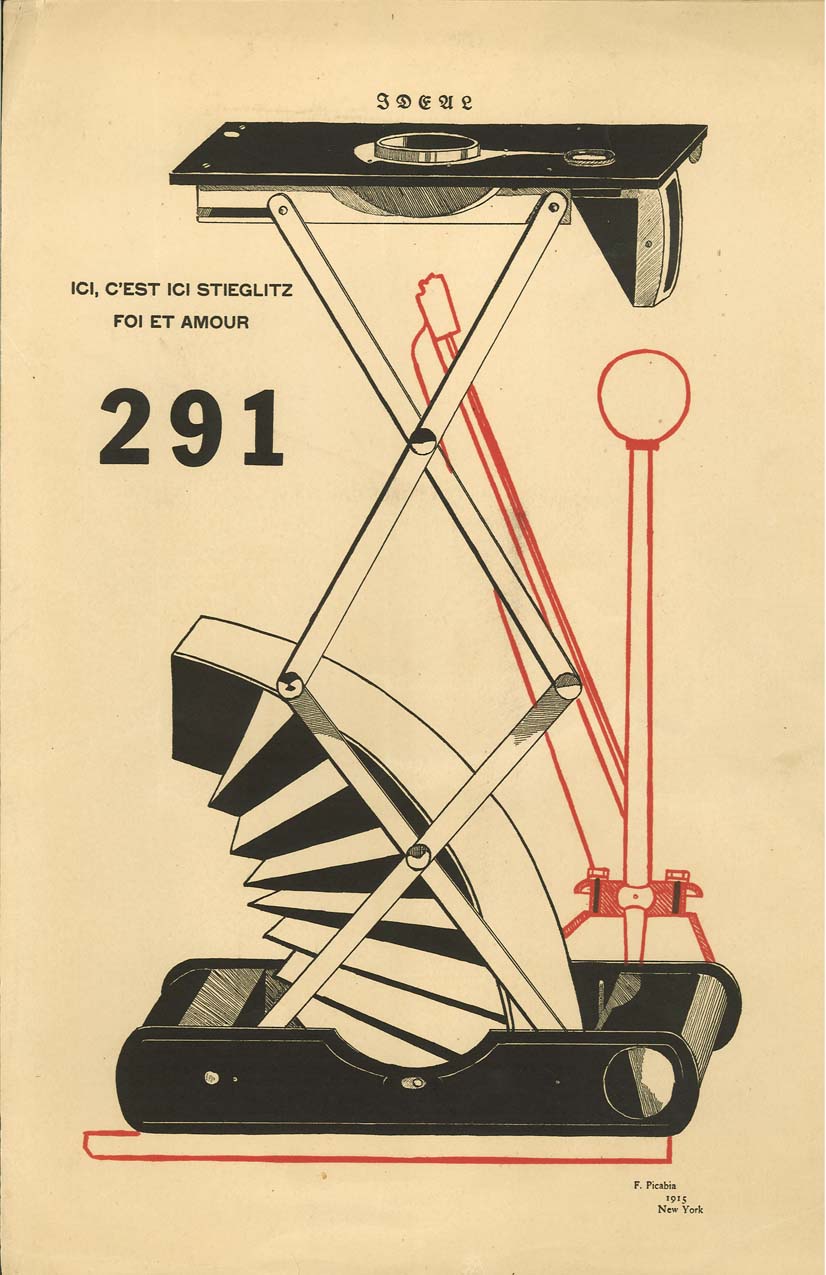

All of these publications are, of course, in their original European languages, though you can find translations of many documents online. The most influential Dada magazine in English, Alfred Stieglitz’s 291, will give monolingual readers a flavor of the larger scene. Published in New York between 1915 and 1916, the short-lived journal included many of the major European names. Its first issue covered experiments like “simultanism,” “sincerism,” and “idiotism,” and introduced visual poetry to American readers. Issue 5–6 featured on its cover one of the weird, nonsensical machines of Francis Picabia.

Dada splintered into other movements before its artists were forced out of Europe or hounded into obscurity by the Nazis. Their unified attempt to fragment and disrupt the dominance of mass culture was itself fragmented and disrupted by a horrific new war machine. But while their ideas may have been co-opted, their spirit may yet live on. Inspired by their work, perhaps a new generation will take up the Sisyphean task of making radical, critical, experimental art to subvert the homogenizing juggernaut of the culture industry.

Enter the University of Iowa’s Digital Dada Library here.

Related Content:

Hear the Experimental Music of the Dada Movement: Avant-Garde Sounds from a Century Ago

Josh Jones is a writer and musician based in Durham, NC. Follow him at @jdmagness

Dada archives should self-destruct as soon as they are put in an institutionalized setting. Please film the event. Thanks. Yours, Dodo.