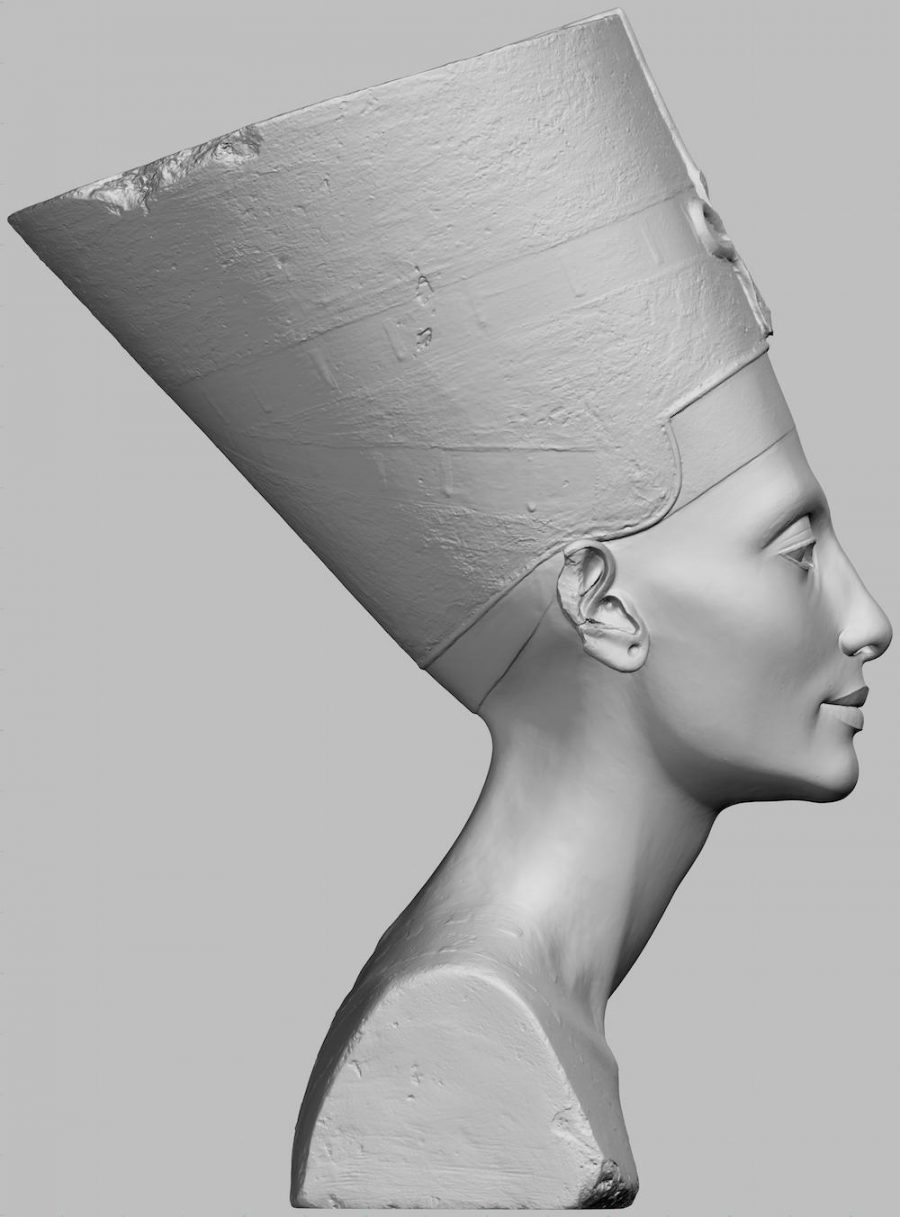

Two years ago, a scandalous “art heist” at the Neues Museum in Berlin—involving illegally made 3D scans of the bust of Nefertiti—turned out to be a different kind of crime. The two Egyptian artists who released the scans claimed they had made the images with a hidden “hacked Kinect Sensor,” reports Annalee Newitz at Ars Technica. But digital artist and designer Cosmo Wenman discovered these were scans made by the Neues Museum itself, which had been stolen by the artists or perhaps a museum employee.

The initial controversy stemmed from the fact that the museum strictly controls images of the artwork, and had refused to release any of their Nefertiti scans to the public. The practice, Wenman pointed out, is consistent across dozens of institutions around the world. “There are many influential museums, universities, and private collections that have extremely high-quality 3D data of important works, but they are not sharing that data with the public.” He lists many prominent examples in a recent Reason article; the long list includes the Venus de Milo, Rodin’s Thinker, and works by Donatello, Bernini, and Michelangelo.

Whatever their reasons, the aggressively proprietary attitude adopted by the Neues seems strange considering the controversial provenance of the Nefertiti bust. Germany has long claimed that it acquired the bust legally in 1912. But at the time, the British controlled Egypt, and Egyptians themselves had little say over the fate of their national treasures. Furthermore, the chain of custody seems to include at least a few documented instances of fraud. Egypt has been demanding that the artifact be repatriated “ever since it first went on display.”

This critical historical context notwithstanding, the bust is already “one of the most copied works of ancient Egyptian art,” and one of the most famous. “Museums should not be repositories of secret knowledge,” Wenman argued in his blog post. Prestigious cultural institutions “are in the best position to produce and publish 3D data of their works and provide authoritative context and commentary.”

Wenman waged a “3‑year-long freedom of information effort” to liberate the scans. His request was initially met with “the gift shop defense”—the museum claimed releasing the images would threaten sales of Nefertiti merchandise. When the appeal to commerce failed to dissuade Wenman, the museum let him examine the scans “in a controlled setting”; they were essentially treating the images, he writes, “like a state secret.” Finally, they relented, allowing Wenman to publish the scans, without any institutional support.

He has done so, and urged others to share his Reason article on social media to get word out about the files, now available to download and use under a CC BY-NC-SA license. He has also taken his own liberties with the scans, colorizing and adding the blue 3D mapping lines himself to the image at the top, for example, drawn from his own interactive 3D model, which you can view and download here. These are examples of his vision for high-quality 3D scans of artworks, which can and should “be adapted, multiplied, and remixed.”

“The best place to celebrate great art,” says Wenman, “is in a vibrant, lively, and anarchic popular culture. The world’s back catalog of art should be set free to run wild in our visual and tactile landscape.” Organizations like Scan the World have been releasing unofficial 3D scans to the public for the past couple years, but these cannot guarantee the accuracy of models rendered by the institutions themselves.

Whether the actual bust of Nefertiti should be returned to Egypt is a somewhat more complicated question, since the 3,000-year old artifact may be too fragile to move and too culturally important to risk damaging in transit. But whether or not its virtual representations should be given to everyone who wants them seems more straightforward.

The images already belong to the public, in a sense, Wenman suggests. Withholding them for the sake of protecting sales seems like a violation of the spirit in which most cultural institutions were founded. Download the Nefertiti scans at Thingiverse, see Wenman’s own 3D models at Sketchfab, and read all of his correspondence with the museum throughout the freedom of information process here. Next, he writes, he’s lobbying for the release of official 3D Rodin scans. Watch this space.

Josh Jones is a writer and musician based in Durham, NC. Follow him at @jdmagness

I acquired a bust of nefertiti 20 plus years ago it has a fingerprint that can e seen it has the Berlin museum on the bottom but her name is spelled neffertete could it be real or fake.thers some large finds out there.