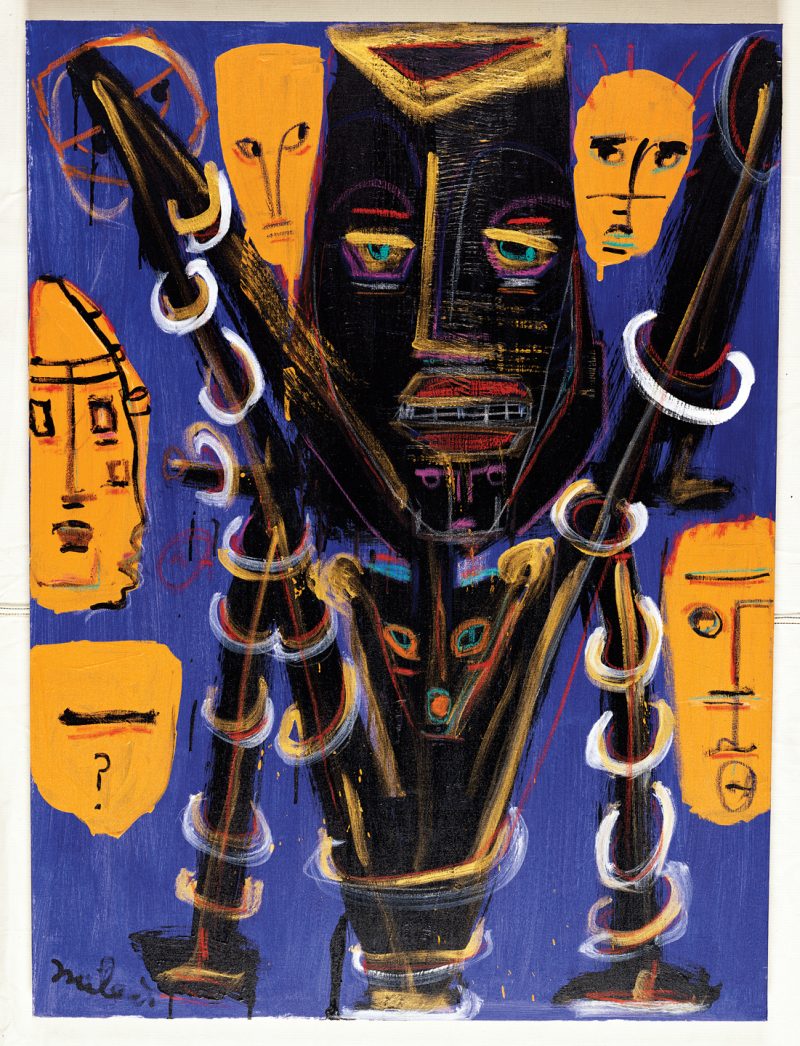

Few artists have lived as many creative lifetimes as Miles Davis did in his 65 years, continuing to evolve even after his death with the posthumous release of a lost album Rubberband earlier this year. The album’s cover, featuring an original painting by Davis himself, may have turned fans on to another facet of the composer/bandleader/trumpeter’s artistic evolution—his career as a visual artist, which he began in earnest just a decade before his 1991 death.

“During the early 1980s,” writes Tara McGinley at Dangerous Minds, Davis “made creating art as much a part of his life as making music…. He was said to have worked obsessively each day on art when he wasn’t touring and he studied regularly with New York painter Jo Gelbard.” Never one to do anything by half-measures, Davis turned out canvas after canvas, though he didn’t exhibit much in his lifetime.

He painted mainly for himself. “It’s like therapy for me,” he said, “and keeps my mind occupied with something positive when I’m not playing music.” Being the intimidating Miles Davis, however, it wasn’t exactly easy for him to find artistic peers with whom he could commune. When he first approached Gelbard, the artist says, “I was scared to death! I could barely speak.”

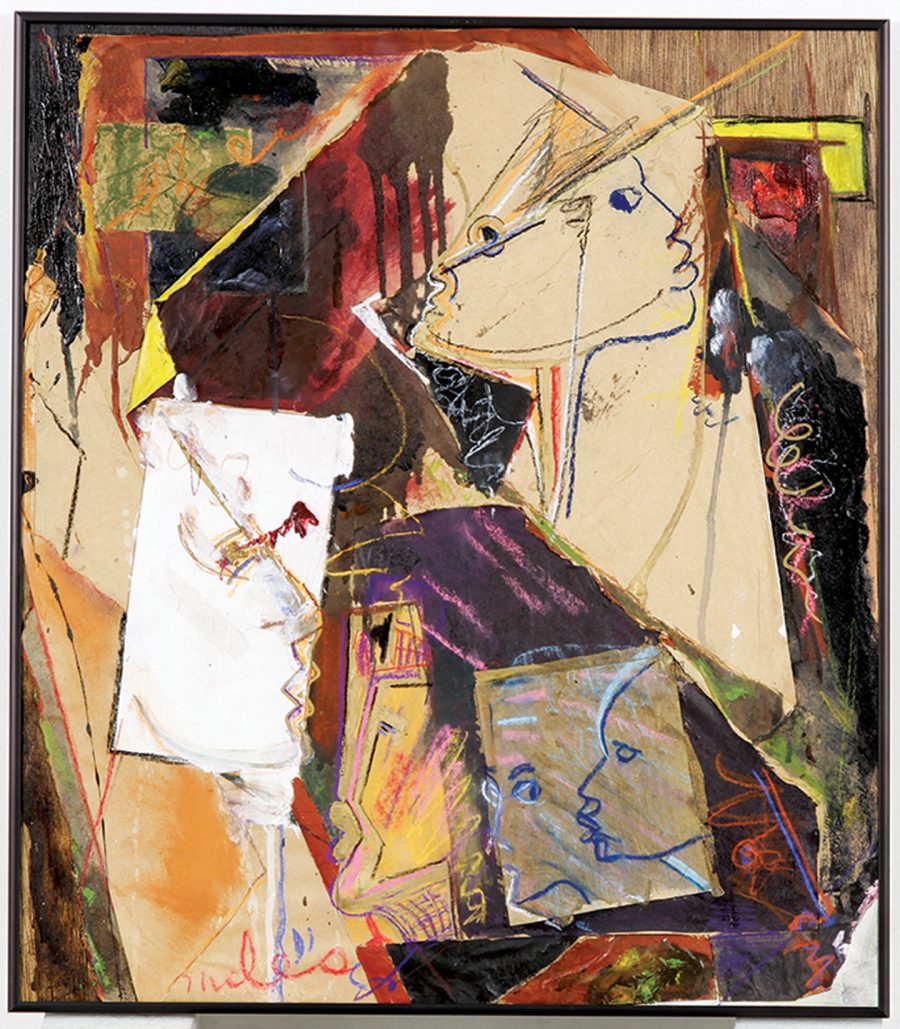

The two lived in the same New York building and Gelbard eventually relaxed enough to give Davis lessons, then later became his girlfriend, collaborating with him on work like the cover of the 1989 album Amandla. As she characterizes his style:

The way Miles painted was not the way he played or the way he sketched. He was so minimal and light-handed in his sound, in his walk. His body was very light; he was a slight man, a delicate kind of guy. His sketches are light and airy and minimal, but when he took his brush and paint, he was deadly – he was like a child with paints in kindergarten. He would pour it on and mix it until it got too muddy and over-paint. He just loved the texture and the feel. It got all over his clothes and his hands and his hair and it was just fun for him…

Miles also found a peer in fellow painter Joni Mitchell. She describes how he called her one day and said, “Joni, I like that painting that you did. Nice colors. I want to come over and watch you paint.” Davis, her musical hero, wouldn’t record with her (though she found out later that he owned all her records). “He would talk painting but he wouldn’t talk music with me.”

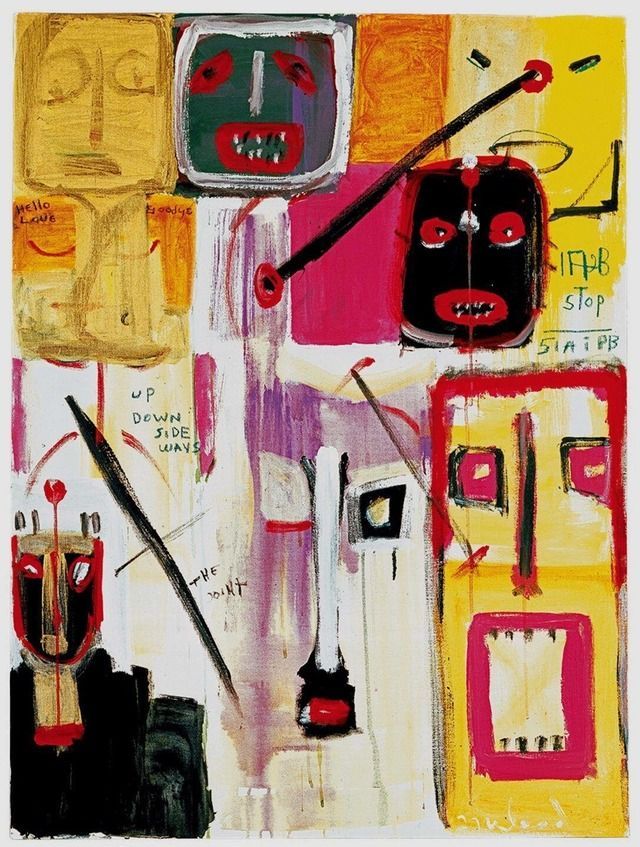

Davis’ paintings are rough and expressionistic, a counterpoint to the formal discipline of his music. (McGinley succinctly describes them as a “sharp, bold and masculine mixture of Kandinsky, Jean-Michel Basquiat, Picasso and African tribal art”.) He didn’t make inroads in the art world, but painting did become “a profitable sideline,” noted the L.A. Times in ’89. Friends and fellow musicians like Lionel Richie and Quincy Jones bought his work. “A magazine called Du in Zurich bought some of my sketches for a special edition they’re putting out on me,” he said.

In 2013, a hardcover edition of his collected paintings appeared, with a foreword by Jones, perhaps the most avid of Miles Davis collectors. There are many other voices in the book, including author Steve Gutterman—who interviewed Davis before his death and writes an introduction—and various family members who contribute personal stories. Miles sums up his own “refreshingly unpretentious attitude” toward his artwork in one brief statement: “It ain’t that serious.”

Pick up a copy of Miles Davis: The Collected Artwork here.

Note: This post updates material that first appeared on our site in 2014.

Related Content:

Kind of Blue: How Miles Davis Changed Jazz

Hear a 65-Hour, Chronological Playlist of Miles Davis’ Revolutionary Jazz Albums

Listen to The Night When Miles Davis Opened for the Grateful Dead in 1970

The Influence of Miles Davis Revealed with Data Visualization: For His 90th Birthday Today

Josh Jones is a writer and musician based in Durham, NC. Follow him at @jdmagness

Wither Jean-Michael Basquiat

Miles paintings (I had no idea) are just plain good. The color is good, the compositions fresh. They work. These are great Sunday painter art-not out to prove anything. They’re rich and would be great to live with. They also expose how awful t he work of Jean-Michael Basquiat is. The equivalent of a fifth grader scratching obscenities on a bathroom stall. His fame is totally unjustified, the lucky result of being the right entrant terrible at the right time.

For the record, Basquiat has so much more going in his art than you give credit. But everyone has their opinion. I hope your work sells for millions, like his. That said, as a friend and early buyer of Jean Michel, ‘before he was famous.’ I see a (possible) strong influence of Miles Davis. But I’ve also seen Basquiat’s influence in young artists who never heard of him. That’s art. No easy answers.

Can we just all accept that art criticism, which at its most daunting can be (not always, but at its worst ) something as dismissive as “this isn’t________” is pointless and even cruel? And certainly unhelpful, not jusrtvto the artist, but finally not to the critic either. When you—anyone—writes that something is worthless, you’re not just belittling someone’s attempt, most often heartfelt and honest, to express how they think and feel, you’re also defining yourself in terms of what you can’t accept. That keeps you locked into what you’ve already accepted, and prevents you from growing, to accept something new.

I’m not dismissing the analysis of art, which is often helpful and can be revelatory, but the urge to categorize what you experience in anything as shallow as .”good” or “bad.”

Nor am I saying it’s wrong to evaluate artistic expression. I am saying: be thoughtful, be slow to judge.