Martin Luther King Jr.’s dream of full inclusion for Black Americans still seems painfully unreal fifty years after his death. By most significant measures, the U.S. has regressed. De facto housing and school segregation are entrenched (and worsening since the 60s and 70s in many cities); voting rights erode one court ruling at a time; the racial wealth gap has widened significantly; and open displays of racist hate and violence grow more worrisome by the day.

Yet the movement was not only about winning political victories, though these were surely the concrete basis for its vision of liberation. It was also very much a cultural struggle. Black artists felt forced by circumstances to choose whether they would keep entertaining all-white audiences and pretending all was well. “There were no more sidelines,” writes Ashawnta Jackson at JSTOR Daily. This was certainly the case for that most American of art forms, jazz. “Jazz musicians, like any other American, had the duty to speak to the world around them, and to oppose the brutal conditions for Black Americans.”

Many of those musicians could not stay silent after the murder of Emmett Till, the 16th Street Baptist Church bombing in Birmingham, and a string of other highly publicized and horrific attacks. Jazz was changing. As Amiri Baraka wrote in a 1962 essay, “the musicians who played it were loudly outspoken about who they thought they were. ‘If you don’t like it, don’t listen’ was the attitude.” That attitude came to define post-Civil Rights Black American culture, a defiant turn away from appeasing white audiences and ignoring racism.

As jazz musicians embraced the movement, so the movement embraced jazz. While King himself is usually associated with the gospel singers he loved, he had a deep respect for jazz as a form that spoke of “some new hope or sense of triumph.” Jazz, wrote King in his opening address for the 1964 Berlin Jazz Festival, “is triumphant music…. When life itself offers no order and meaning, the musician creates an order and meaning from the sounds of the earth which flow through his instrument. It is no wonder that so much of the search for identity among American Negroes was championed by Jazz musicians.”

Jazz not only gave order to chaotic, “complicated urban existence,” it also provided critical emotional support for the Movement.

Much of the power of our Freedom Movement in the United States has come from this music. It has strengthened us with its sweet rhythms when courage began to fail. It has calmed us with its rich harmonies when spirits were down.

King’s take on jazz paralleled his articulations of the movement’s goals—he always understood that the particular struggles of Black Americans had specific historical roots, and required specific political remedies. But ultimately, he believed that everyone should be treated with dignity and respect, and have access to the same opportunities and the same protections under the law.

Jazz is exported to the world. For in the particular struggle of the Negro in America there is something akin to the universal struggle of modern man. Everybody has the Blues. Everybody longs for meaning. Everybody needs to love and be loved. Everybody needs to clap hands and be happy. Everybody longs for faith.

Jazz music, said King, “is a stepping stone towards all of these.” Wrought “out of oppression,” it is music, he said, that “speaks for life,” even in the midst of what could seem like death and defeat. Read King’s full address at WCLK 91.9. And at the top of the post, hear the speech read by San Francisco Bay Area artists for a 2012 celebration on King’s birthday.

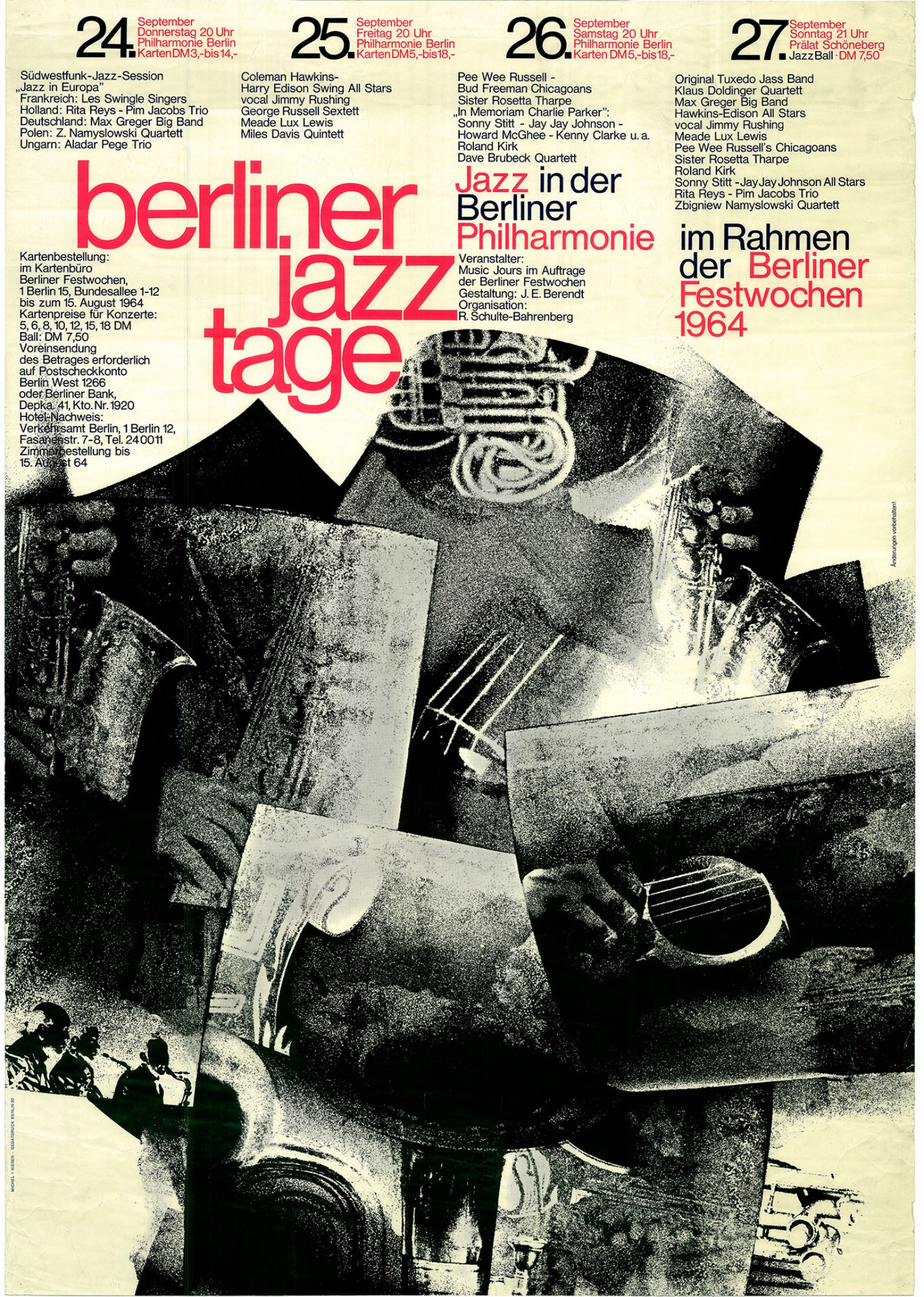

The 1964 Berlin Jazz Festival (poster above) was the first in the illustrious annual event. See many other stunning posters from the series here.

via JSTOR Daily

Related Content:

Hi, I just read the article about how jazz was able to ease the burden and and the discomfort black American were enduring during the segregation period in America and how Martin Luther King jnr supported the Idea, I would like to know about Jazz Please help me with books and Jazz CD such as the likes of Miles Davis, Duke Ellington, Dizzy Gillespy and many more, Please help.

King’s words are indeed brilliant, the best such succinct a summation as I’ve seen about the nature of the music. But this is not the text of a speech. He was not in Berlin at that time. King wrote these words as a preface, foreword, introduction or whatever to the program book for the first Berlin Jazz Festival, and that is where they were first published.

Please find a used copy of the Penguin Guide to Jazz and dip in. There are about 8 editions, if I remember correctly. It’s a great resource.

Then look for playlists on your favourite streaming service, or join Jazz Vinyl Lovers on FB (Ken Micallef’s group) for more help and learning. Best of luck!

Here are some suggestions, with a few more names. These are discs with some of the greatest music of each musician and / or a good entry point into their musis. Louis Armstrong: Portrait of the Artist as a young man (3‑CD set); Billie Holiday with Lester Young: A Musical Romance; Duke Ellington: Never no lament (3‑CD set); Charlie Parker: Best of the complete Savoy and Dial stuido recordings; Dizzy Gillespie Sure ‘Nuff; Miles Davis: Kind of Blue; Thelonious Monk: Thelonious Monk trio (Prestige); Bill Evans: Portrait in Jazz; Charles Mingus: Mingus Ah Um; John Coltrane: Coltrane plays the blues (Atlantic); Ornette Coleman: The Change of the Century (Atlantic); Henry Threadgill: Just the Facts and Pass the Bucket

There´S SO MUCH MORE, of course, but thse would make a great start!

Some books: Ted Gioia: The History of Jazz; Martin Williams: The Jazz Tradition; and from a more militant black point of view: Leroy Jones (Amari Baraka): Blues People

Good luck!!And a little suggestion: if you don’t like something, leave it for a bit, and try it again later!!

In my reply to Mandla Zwane’s appeal for help I made a careless mistake. The title of a famou Dizzy Gillespie piece, whichi is also the title of the CD I recommended, is a play on words; it’s not Sure Nuff, but Shaw Nuff, dedicated to Billy Shaw, a promoter who organized Gillespie’s and Parker’s visit to the West Coast in (I think) 1946.

I’m curious to know if Dr. Martin Luther King Jr. met jazz musician “Cat” Anderson while he was in Greenville, SC. about a year before Dr. MLK Jr. was murdered or if he knew “Cat” Anderson at all, as I have read much about Dr. MLK Jr.’s love for jazz music. “Cat” Anderson the jazz musician died April 29, 1981. My nickname (from Catherine) is “Cat” Anderson. I was born April 30th, 1981. Dr. MLK Jr. visited and spoke in Greenville, SC in the 1960’s (can’t remember the year), but the day was April 30th.