The early 20th century artistic and literary revolution called Modernism appears in history as an almost entirely European-American phenomenon. Textbooks and syllabi tend to leave out important modernist movements on other continents, which means we miss out on important cross-continental conversations. Though, to be fair, very few English-speaking textbook writers and teachers have known much about the work of, Mavo, an avant-garde group of Japanese artists from the 1920s.

Scant literature has been available in translation. Critics “were often dismissive of the group,” notes Margaret Carrigan at Hyperallergic, “and art historians have all but ignored them in favor of larger contemporaneous movements, like German Expressionism.” Whatever the reasons for the slighting of early Japanese modernism, we can now try to rectify the imbalance thanks to online sources covering the fascinating history of Mavo—both its interesting parallels with European Modernism and its important differences.

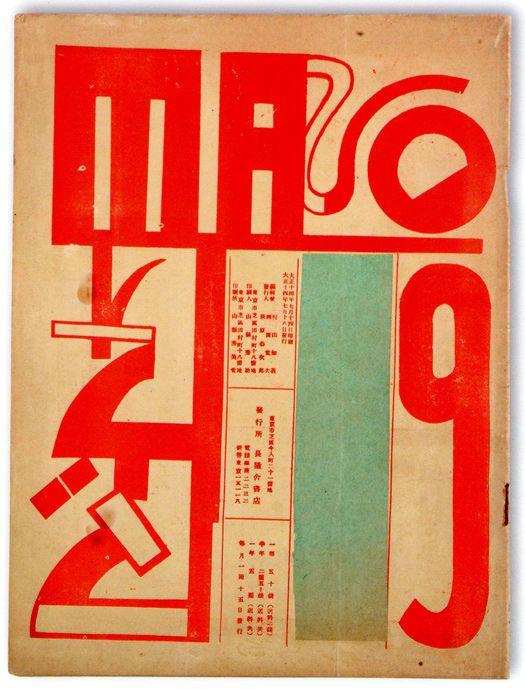

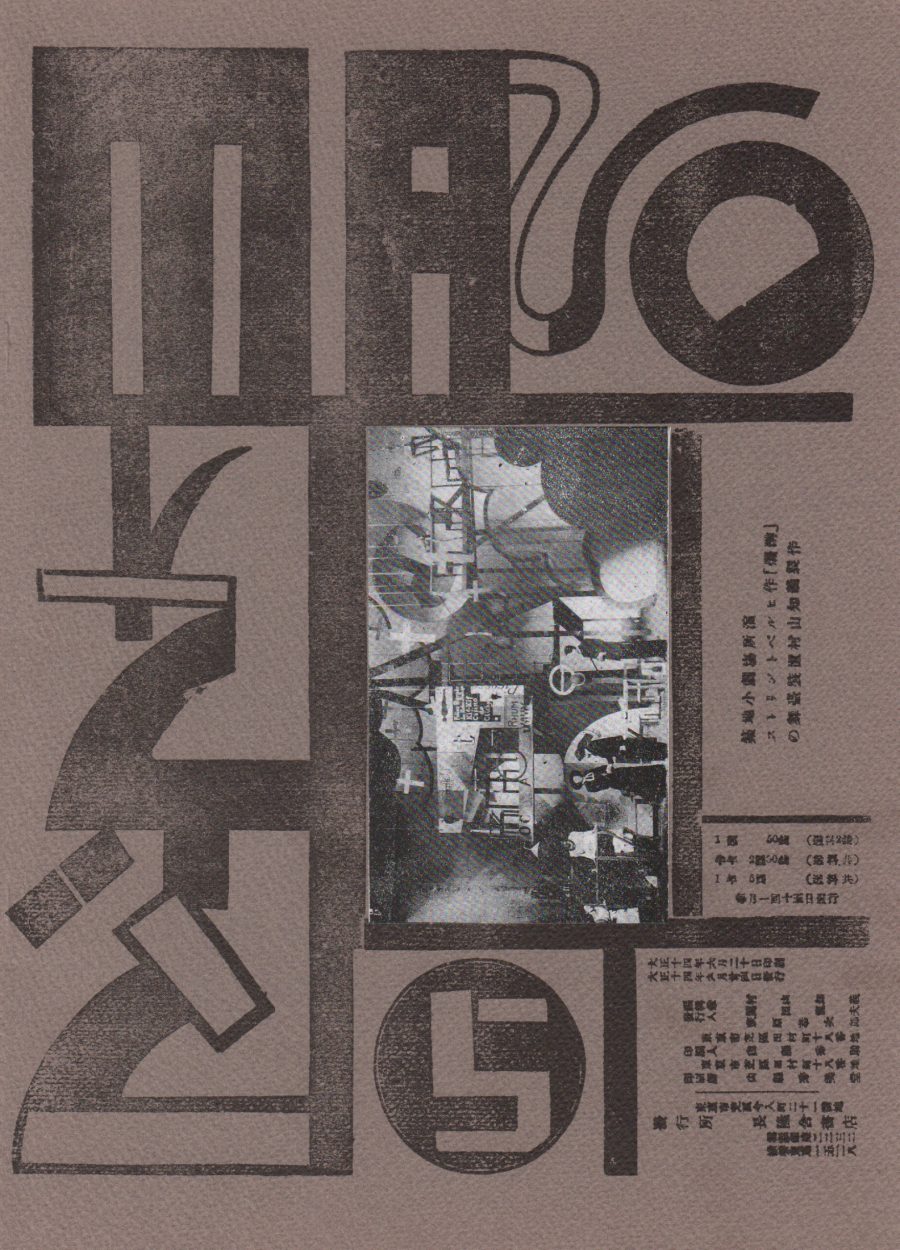

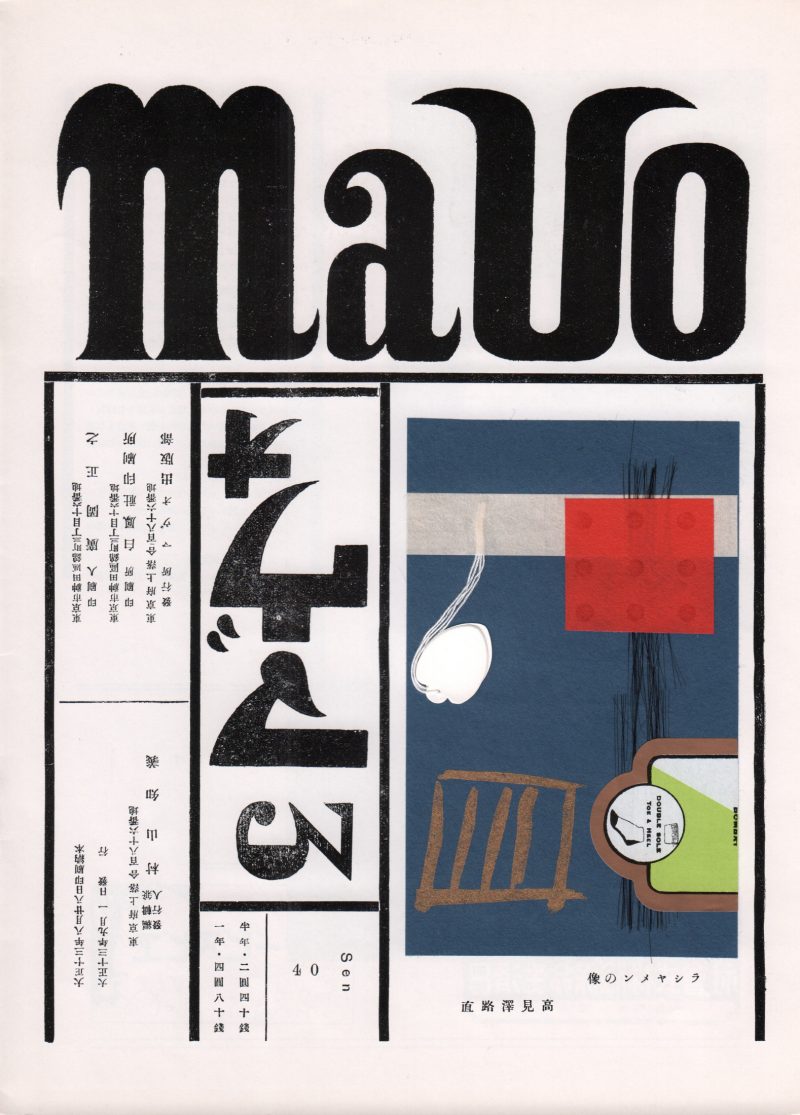

Or we can begin to get an intriguing sense of these things, more or less, depending on our level of familiarity with Japanese language and culture. MAVO magazine, edited by Tatsuo Okada and Tomoyoshi Murayama, “appeared in 7 issues between July 1924 and August 1925,” writes Monoskop, who host six of those issues in high resolution scans. (Click on the PDF link under the image of each cover.) “By the third issue, the magazine was thick with advertisements and the usage of actual newspaper as its pages.” The original linocuts and “photographic reproductions of assemblage, painting, and graphic works” are small and sometimes inscrutable in grayscale.

There are many affinities with European modernisms—dichotomies of playfulness and precision, the love of collage and industrial machinery. The history of Mavo, like that of modernists worldwide, is a history of anarchic, confrontational art, charged with contempt for tradition. In 1923, the Shin-aichi newspaper, notes The Japan Times, covered the story of a Mavo exhibit in which artist Takamizawa Michinao tossed rocks through the windows of a state-sponsored, traditional art exhibit while Mavo artists displayed their own abstract canvases outside the gallery.

Mavo came about as the rebranding of an earlier group, “Japan’s Association of Futurist Artists, which became the local offshoot of the European Futurist phenomenon that began in Italy in 1909.” They were eclectic, publishing criticism, designing posters, buildings, and dance and theater pieces, incorporating Cubism and Dadaist tendencies. Unlike the Italian Futurists, who became increasingly fascist in their orientation, Mavo opposed the conservative state. “The Great Kanto Earthquake of 1924 brought about a proletarian and socialist bent to Mavo activities.”

See more of MAVO magazine at Monoskop, and learn more about the movement at The Japan Times, Hyperallergic, and Monoskop’s bibliography of a few scholarly sources in English (and Japanese, if you read the language). Also see Gennifer Weisenfeld’s book, MAVO: Japanese Artists and the Avant-Garde, 1905–1931. If the phrase Japanese avant-garde calls up names like Yoko Ono and Yayoi Kusama, now it may also bring to mind the earlier Mavo and the many artists under its umbrella who adapted European influences for Japanese modes of artistic revolution.

Related Content:

Extensive Archive of Avant-Garde & Modernist Magazines (1890–1939) Now Available Online

Josh Jones is a writer and musician based in Durham, NC. Follow him at @jdmagness

Very interesting. Thank you so much for the research done.

OC is a Daily refreshment in these C‑times.

The link is sent to my good Japanese friend Tatsuo Wakabayashi