Whether you see it as a good faith effort to correct past mistakes or a bid to distract from more recent fumbles—the New York Times’ “Overlooked” obituary series has done its readers a service by recovering the bios of “remarkable people whose deaths… went unreported in The Times.” Most of the profiles are of people who were public figures at the time of their death. Some had achieved international recognition, like Alan Turing, and others were royalty, like Rani, queen of the kingdom of Jhansi in Northern India and one of the leaders of a revolt against the British in 1857.

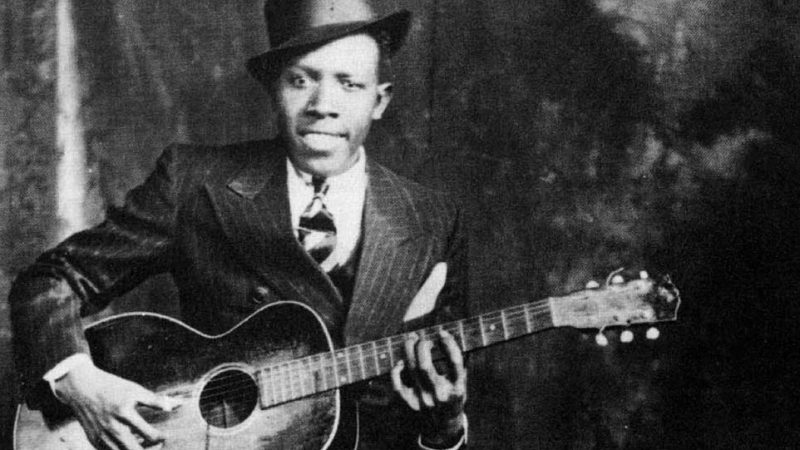

The latest “Overlooked” is an oddity. Its subject may be the most famous person of all to get the belated Times obit since the series began. Robert Johnson’s alleged deal with the devil at the crossroads has become as foundational to U.S. mythology as John Henry’s hammer or George Washington’s cherry tree.

At the very same time, Johnson may be the most obscure figure to appear in “Overlooked.” And the person about whom the least is known. “What is known” about him, writes the Times, “can be summarized on a postcard.”

He is thought to have been born out of wedlock in May 1911 in Mississippi and raised there. School and census records indicated he lived for stretches in Tennessee and Arkansas. He took up guitar at a young age and became a traveling musician, eventually glimpsing the bustle of New York City. But he died in Mississippi [in 1938], with just over two dozen little-noticed recorded songs to his name.

There’s more to the story, but it gets hard to tell where the historical record ends and the mythology begins. Still, the paper of record can be forgiven for overlooking Johnson the first time around. Aside from a small number of Delta blues fans, most of whom actually lived in the Delta, hardly anyone knew who Robert Johnson was in life. By the time news of his mojo started to spread outside Mississippi, it was too late. John Hammond sought to bring him Carnegie Hall in 1938, the year of his death. Alan Lomax looked to record him 1941, only to find out he was gone.

His fame spread in the 1960s when British Blues invasionists picked up on his genius, cited him as a primary influence, and covered and adapted his songs. Bob Dylan wrote in his memoir Chronicles: Volume One that “hundreds of lines” of his derive from Johnson’s influence. The “advent of rock ’n’ roll would turn Johnson into a figure of legend,” among blues and rock and roll fans in the know. The legend, and recognition of Johnson’s greatness, exploded in subsequent decades.

Johnson was inducted into the Rock and Roll Hall of Fame in its first ceremony in 1986. His posthumous Complete Recordings won a Grammy in 1991. Many more honors followed, including a Grammy lifetime achievement award. By 2003, Rolling Stone could call Johnson “the undisputed king of the Mississippi Delta blues” and place him at #5 on their list of 100 greatest guitarists of all time. How is it possible that an obscurely minor figure in blues history became a founding grandfather of rock and roll?

“The chasm between the man Johnson was and the myth he became,” the Times admits “has marooned historians and conscientious listeners for more than a half-century.” Johnson’s story “is no more or less than the handiwork of the country in which it was written; a country where the legacy of African-Americans has often been shaped by others.” But those others have had good reason for appropriating Johnson’s infernal story and unique musical signatures.

A new Netflix documentary ReMastered: Devil at the Crossroads (see the trailer above) explores in interviews with rock and blues greats how Johnson became forever linked to a myth that stood in for the real circumstances of his short, difficult life. (He can be thought of as the founding member of rock’s tragically elite “27 club.”) Actual deal with the devil or no, “there was certainly a lot of daredevilry in his flouting of standard tempos and harmonics,” writes Rolling Stone. “His records are breathtaking displays of melodic development and acute brawn.”

While the Times, and most everyone else, passed over him in life, in death, he has more than received his due from musicians and fans. Johnson has not been overlooked so much as maybe overrepresented in the history of the blues. Find out why in his belated Times obituary, in the hundreds of tributes to him written and recorded since his death 81 years ago, and by immersing yourself in his own haunting recordings.

Related Content:

The Story of Bluesman Robert Johnson’s Famous Deal With the Devil Retold in Three Animations

The Legend of Bluesman Robert Johnson Animated

Josh Jones is a writer and musician based in Durham, NC. Follow him at @jdmagness

Strangely the Times appears to view the legend of Johnson selling his soul to the devil as possibly factual, something he could have corroborated.

In fairness to the NYT, Johnson was still only a local celebrity at the time he died and known mostly to black audiences. Relatively few people outside the rural part of Mississippi where he was from would even have known who he was and probably none of them lived in the NYT circulation area.

As Bruce Conforth, co-author of the Robert Johnson bio, “Up Jumped the Devil” points out the Times obit is full of errors. In fact, there is quite a bit we know about Johnson that is not in the obit. You certainly need to read it yourself. And he did not sell his soul to the devil.