He only published two books of philosophy, and only one of them in his lifetime, but Ludwig Wittgenstein’s influence on 20th century thought is incalculable. Both of his books, the Tractatus Logico-Philosophicus and the posthumous Philosophical Investigations, constitute major turning points in analytic philosophy—the one inspiring the 1920s logical positivism of the Vienna Circle, the other repudiating Wittgenstein’s earlier thought and invigorating mid-century pragmatism and the Ordinary Language school.

“By the 1930s,” notes Tim Rayner at Philosophy for Change, “Wittgenstein had decided” that the theory of language he had advanced in the Tractatus “was quite wrong. He devoted the rest of his life to explaining why.” This marked a dramatic shift away from the work that first made him famous, but Wittgenstein never did anything halfway. After publishing the Tractatus—partly composed while he fought in World War I—the Austrian son of a wealthy Viennese industrialist announced that he had solved all of the problems in philosophy. Nothing more needed to be said on the matter.

He “retired” to try his hand at several other trades, including grade school teacher, for a period of about six years in rural villages in Austria. “By the time he decided to teach,” Spencer Robins notes at The Paris Review, “Wittgenstein was well on his way to being considered the greatest philosopher alive.” He couldn’t have cared less. “Convinced he was a moral failure, he took extreme steps to change his circumstances, divesting himself of his enormous family fortune” and choosing a profession “influenced by a romantic idea of what it would be like to work with peasants—an idea he’d gotten from reading Tolstoy.”

Wittgenstein was an unsparing taskmaster, by all accounts. His brief elementary teaching career ended abruptly in 1926 when he viciously attacked a student. While his personality did not suit him to the role at all, his pedagogy was apparently very effective. Wittgenstein “engaged his students in a sort of ‘project-based learning’ that wouldn’t be out of place in the best elementary classrooms today,” writes Robins. In the last years of teaching, he worked with his students to produce what is technically his second published book—Wörterbuch für Volksschulen, a German spelling dictionary for elementary schools.

One of the shocks that awaited the philosopher when he arrived in rural schools was the expense of books, and students’ inability to obtain them. “I had never realized dictionaries would be so mightily expensive,” he told educationalist Ludwig Hansel. “I think, if I live long enough, I will produce a small dictionary for elementary schools.” Often a pragmatist in life, if not always in his thought, Wittgenstein took the opportunity to turn this promise into a teachable moment, testing drafts of his dictionary in the classroom. “The improvement of spelling was astonishing,” he remarked.

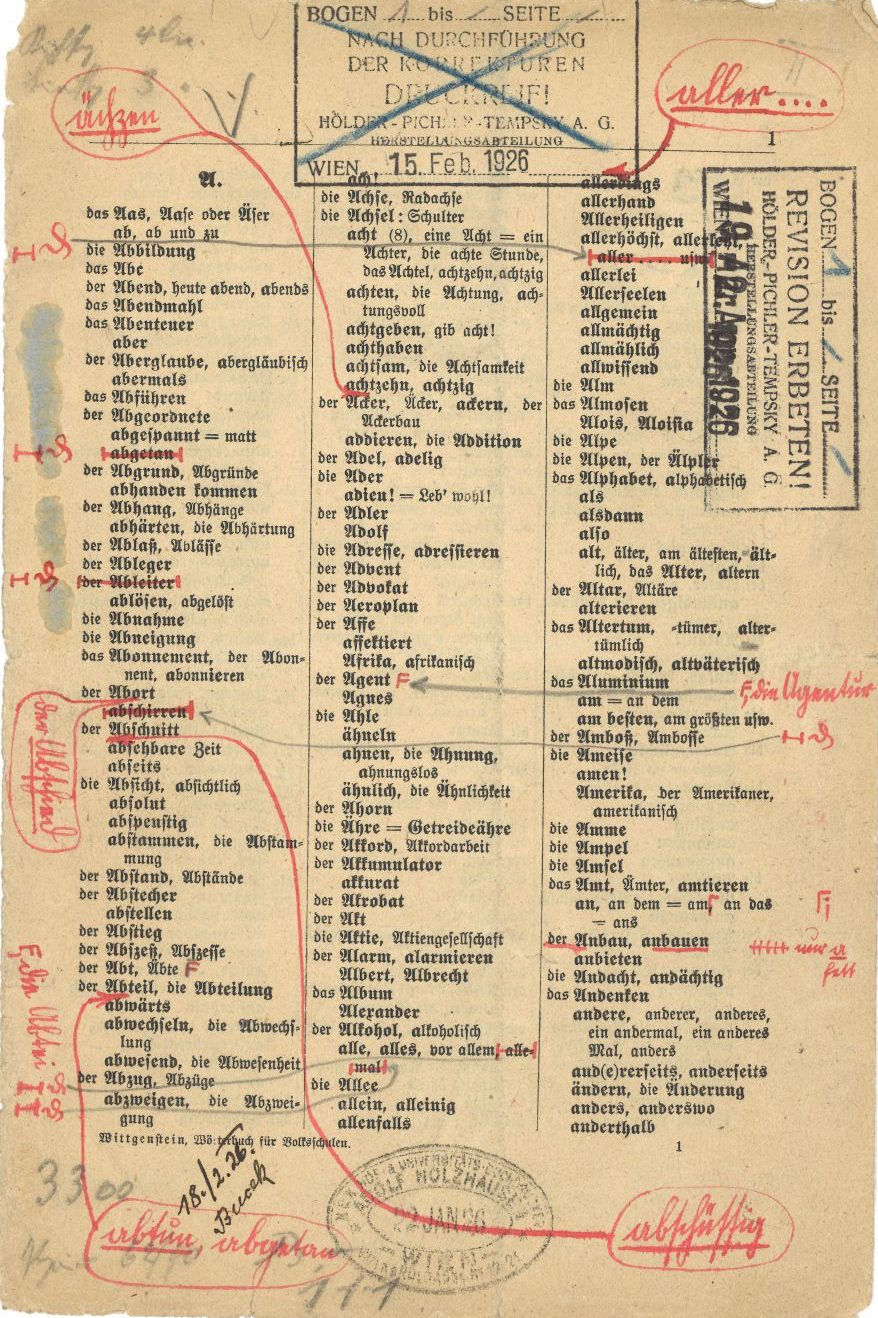

The dictionary, and Wittgenstein’s teaching methods in general during this period, “reveal his continued interest in the philosophy of language and its practical, everyday manifestations,” as Désirée Weber, Assistant Professor of Political Theory at the University of Wooster in Ohio, writes at the British Wittgenstein Society site. Copies of the 42-page book are extremely rare. The page above comes from a set of proof pages discovered and examined by Weber. The pages show the philosopher tailoring his reference guide to the world his students knew and the language they already spoke.

“Although there is some question” which, or whether, the various editorial marks are in Wittgenstein’s own hand, “the contents of the dictionary and the corrections yield a fascinating view of the words that Wittgenstein deemed central to the forms of life and language-games in which his students were immersed.” He captured “the specificity of the rural Austrian dialect,” Weber writes at the Wittgenstein Initiative, as well as “words that pertained to cultural practices that were part of their community and with which they would have been well acquainted.”

Wittgenstein elaborates his practical purpose in an introduction, showing his intent to initiate his students into their “language-using community” and into “the responsibility this carries,” Weber writes. The project also shows him engaging in the theoretical work that would occupy him for the rest of his career.

Related Content:

Ludwig Wittgenstein’s Short, Strange & Brutal Stint as an Elementary School Teacher

In Search of Ludwig Wittgenstein’s Secluded Hut in Norway: A Short Travel Film

Josh Jones is a writer and musician based in Durham, NC. Follow him at @jdmagness

Leave a Reply