This time each summer, as the conclusion of this year’s fortnight-long championship at Wimbledon approaches, even the most private of the tennis enthusiasts in all of our circles make themselves known. Love of that particular game runs down all walks of life, but seems to exist in particularly high concentrations among cultural creators: not just writers like Martin Amis, Geoff Dyer, and David Foster Wallace, all of whose bodies of work contain eloquent thoughts on tennis, but composers of music as well.

Take Arnold Schoenberg, who well into his old age continued not just to create the innovative music for which we remember him, but to spend time on the court as well. Though born in Vienna, Schoenberg eventually landed in the right place to enjoy tennis on the regular: southern California, to which he fled in 1933 after being informed of how inhospitable his homeland would soon become to persons of Jewish heritage. Few famous composers of that time had less in common than Schoenberg and George Gershwin, but their shared enjoyment of tennis made them into fast partners.

According to Howard Pollack’s life of Gershwin, fellow composer Albert Sendrey left a “revealing account” of one of the weekly matches between “the thirty-eight-year-old Gershwin and the sixty-two-year-old Schoenberg, contrasting the alternately ‘nervous’ and ‘nonchalant,’ ‘relentless’ and ‘chivalrous’ Gershwin, ‘playing to an audience,’ with the ‘overly eager’ and ‘choppy’ Schoenberg who ‘has learned to shut his mind against public opinion.’ ” Any parallels between playing style and musical sensibility are, of course, entirely coincidental.

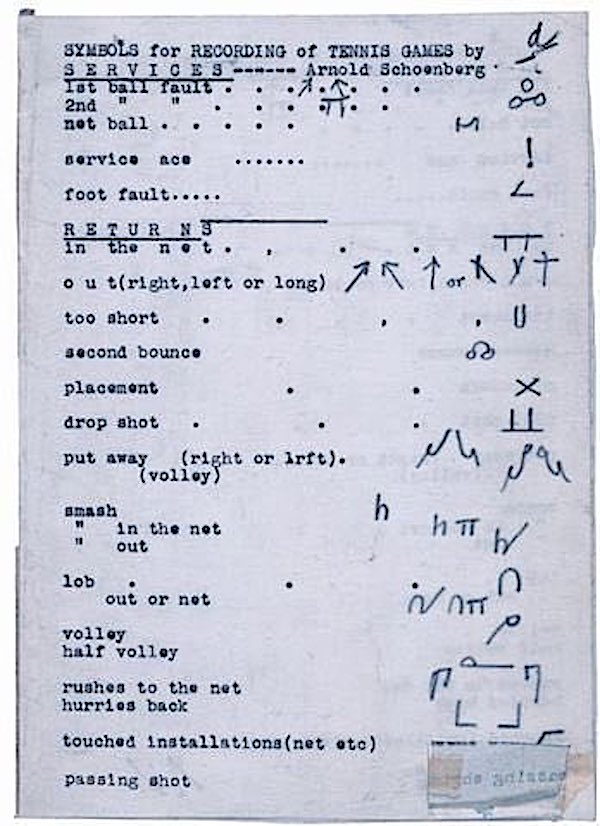

The cerebral nature of Schoenberg’s compositions may not suggest a temperament suited for physical activity of any kind, but even in Austria Schoenberg had been a keen sportsman. And as a fair few tennis-loving writers have explained, the game does possess an intellectual side, and one made more easily analyzable, at least in theory, by a system of Schoenberg’s invention. “Toward the end of his life, Schoenberg — always fascinated by rules, analysis, and invention — would come up with a form of notation to transcribe the tennis matches of his athlete son Ronald,” writes Mark Berry in Arnold Schoenberg. You can see this system laid out on the sheet above, recently posted on Twitter by Henry Gough-Cooper.

The marks look vaguely similar to those of certain dance notation systems, a natural enough resemblance considering the kind of footwork tennis demands. But ideally, Schoenberg’s notation would also have rendered a game of tennis as comprehensible as one of chess — another pursuit to which Schoenberg applied his mind. He came up with “an expanded four-player, ten-square version of the traditional game,” writes Berry, “involving superpowers and lesser powers all compelled to forge alliances, with new pieces such as airplanes, tanks, submarines, and so forth.” Schoenberg’s “coalition chess,” as he called it, seems to have caught on no more than his tennis notation system did. But then, the man who pioneered the twelve-tone technique never did go in for mass acceptance.

via @NotationIsGreat and Henry Gough-Cooper on Twitter

Related Content:

Vi Hart Uses Her Video Magic to Demystify Stravinsky and Schoenberg’s 12-Tone Compositions

John Coltrane Draws a Picture Illustrating the Mathematics of Music

Bob Dylan and George Harrison Play Tennis, 1969

Based in Seoul, Colin Marshall writes and broadcasts on cities, language, and culture. His projects include the book The Stateless City: a Walk through 21st-Century Los Angeles and the video series The City in Cinema. Follow him on Twitter at @colinmarshall, on Facebook, or on Instagram.

Leave a Reply