Religions take the cast and hue of the cultures in which they find root. This was certainly true in Tibet when Buddhism arrived in the 7th century. It transformed and was transformed by the native religion of Bon. Of the many creative practices that arose from this synthesis, Tibetan Buddhist music ranks very highly in importance.

As in sacred music in the West, Tibetan music has complex systems of musical notation and a long history of written religious song. “A vital component of Tibetan Buddhist experience,” explains Google Arts & Cultures Buddhist Digital Resource Center, “musical notation allows for the transference of sacred sound and ceremony across generations. A means to memorize sacred text, express devotion, ward off feral spirts, and invoke deities.”

Some of these features may be alien to secular Western Buddhists focused on mindfulness and silent meditation, but to varying degrees, Tibetan schools place considerable value on the aesthetic experience of extra-human realms. As University of Tulsa musicologist John Powell writes, “the use of sacred sound” in Tibetan Buddhism, a “Mantrayana” tradition, acts “as a formula for the transformation of human consciousness.”

Tibetan musical notations, Google points out, “symbolically represent the melodies, rhythm patterns, and instrumental arrangements. In harmony with chanting, visualizations, and hand gestures, [Tibetan] music crucially guides ritual performance.” It is characterized not only by its integration of ritual dance, but also by a large collection of ritual instruments—including the long, Swiss-like horns suited to a mountain environment—and unique forms of polyphonic overtone singing.

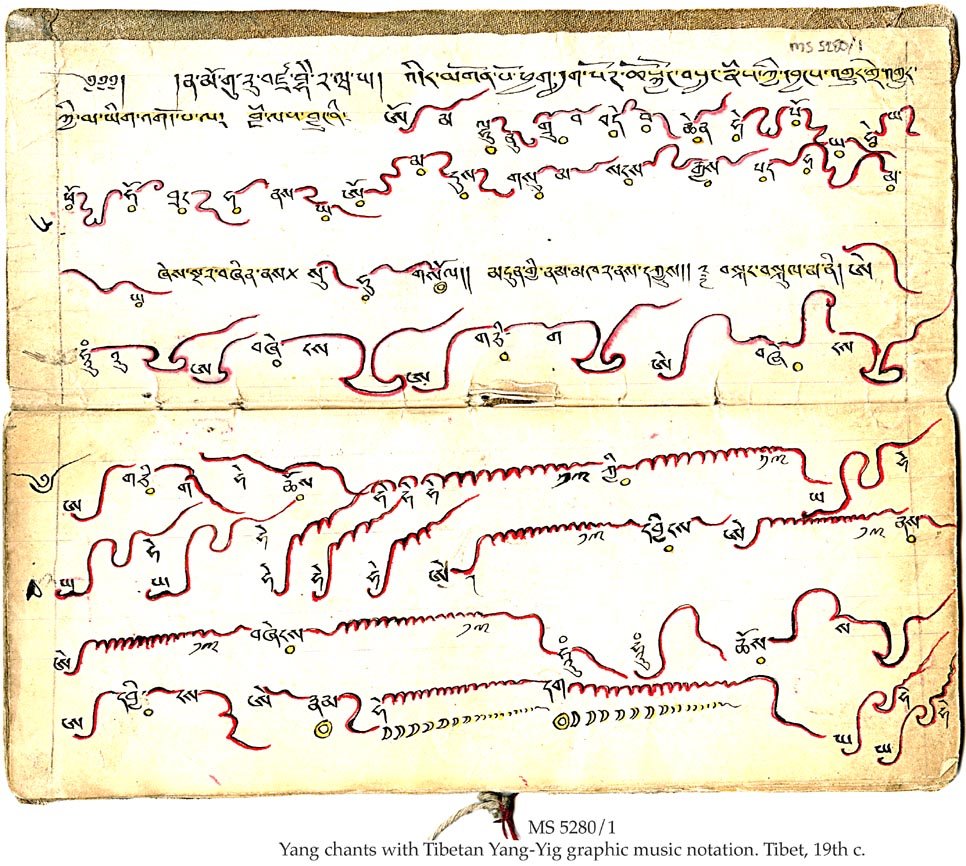

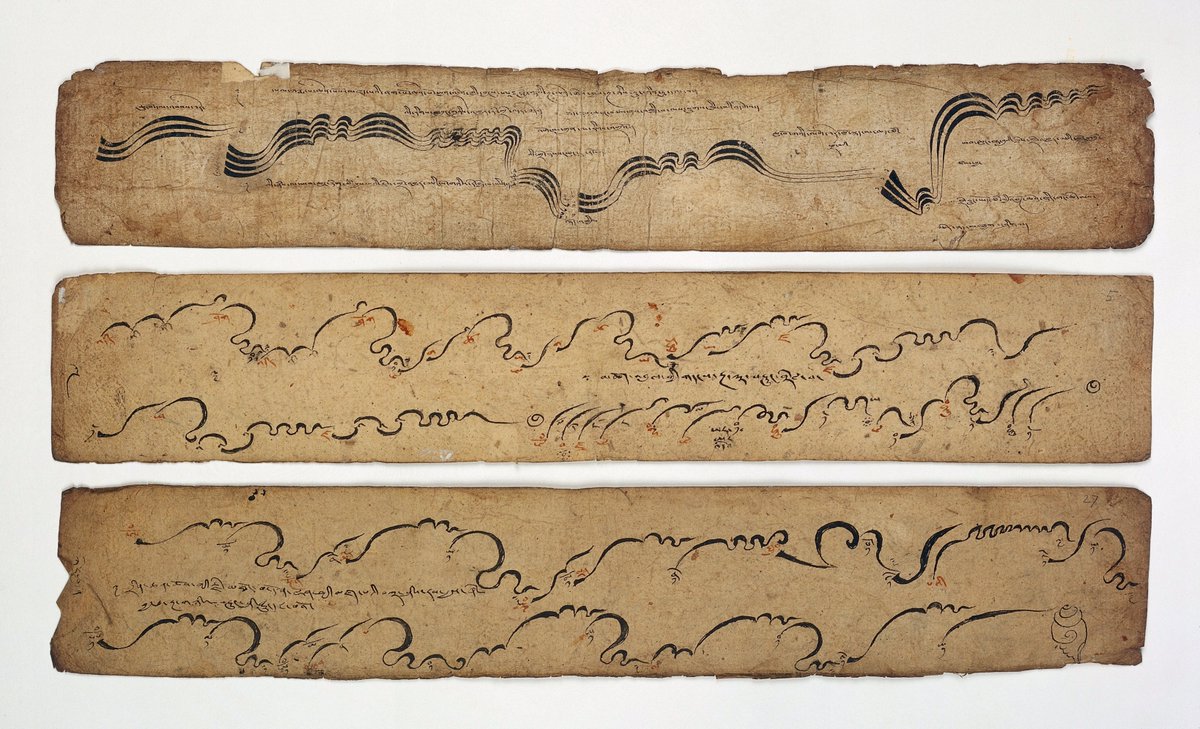

The examples of musical notation you see here came from the appropriately-named Twitter account Musical Notation is Beautiful and typeface designer and researcher Jo De Baerdemaeker. At the top is a 19th century manuscript belonging to the “Yang” tradition, “the most highly involved and regarded chant tradition in Tibetan music,” notes the Schoyen Collection, “and the only one to rely on a system of notation (Yang-Yig).”

The curved lines represent “smoothly effected rises and falls in intonation.” The notation also “frequently contains detailed instructions concerning in what spirit the music should be sung (e.g. flowing like a river, light like bird song) and the smallest modifications to be made to the voice in the utterance of a vowel.” The Yang-Yig goes all the way back to the 6th century, predating Tibetan Buddhism, and “does not record neither the rhythmic pattern nor duration of notes.” Other kinds of music have their own types of notation, such as that in the piece above for voice, drums, trumpets, horns, and cymbals.

Though they articulate and elaborate on religious ideas from India, Tibet’s musical traditions are entirely its own. “It is essential to rethink the entire concept of melody and rhythm” to understand Tibetan Buddhist chant, writes Powell in a detailed overview of Tibetan music’s vocal and instrumental qualities. “Many outside Tibetan culture are accustomed to think of melody as a sequence of rising or falling pitches,” he says. “In Tibetan Tantric chanting, however, the melodic content occurs in terms of vowel modification and the careful contouring of tones.” Hear an example of traditional Tibetan Buddhist chant just above, and learn more about Tibetan musical notation at Google Arts & Culture.

via @NotationIsGreat

Related Content:

The World’s Largest Collection of Tibetan Buddhist Literature Now Online

Free Online Course: Robert Thurman’s Introduction to Tibetan Buddhism (Recorded at Columbia U)

Leonard Cohen Narrates Film on The Tibetan Book of the Dead, Featuring the Dalai Lama (1994)

Josh Jones is a writer and musician based in Durham, NC. Follow him at @jdmagness

Leave a Reply