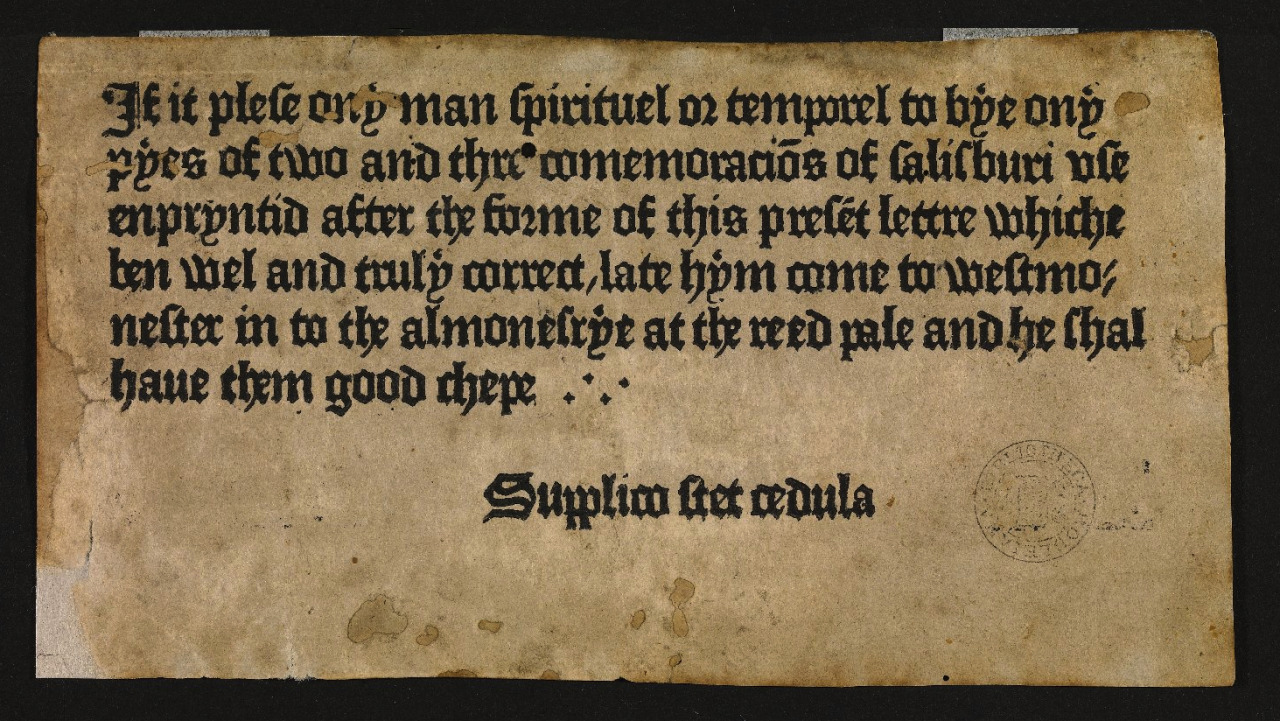

Nobody pays much mind to advertising, at least the haphazard kind of advertising that clutters the space around us. But here in the 21st century, when both that space and the ads that appear throughout it are as likely to be digital as physical, we might take a moment to look back at how the practice of putting up notices to sell things began. In the English language, it goes back to at least to the mid-fifteenth century — specifically, to the year 1476, when Britain’s first printer William Caxton produced not just a manual for priests called Sarum Pie (or the Ordinale ad usum Sarum), but easily postable, playing card-sized advertisements for the book as well.

“This piece of paper, of which two copies survive, is regarded as the earliest surviving printed advertisement in the English language,” writes Erik Kwakkel at medievalbooks. It states that Sarum Pie “is printed in the same letter type as the advertisement (‘enpryntid after the forme of this present lettre,’ line 3). Even without having seen the new book, its key feature, the type, can thus already be assessed.” This pioneering advertisement also “reassures potential clients that the text of the handbook is ‘truly correct’ (line 4) and that it can be acquired cheaply (‘he shal have them good chepe,’ lines 5–6). Both features will have been welcomed by priests, the target audience, who needed their textual tools to be flawless and did not have much money to spend on them.”

Kwakkel also gets into other notable features of this deceptively simple-looking production, including “the precise location of Caxton’s shop,” a warning in Latin urging readers not to remove the notice (“showing that it was put on display somewhere,” perhaps a church porch), and even the type. In both the advertisement and Sarum Pie itself, “the letter shapes lack ‘sharpness:’ frequently ‘blobs’ and small hairlines appear as letters, while an individual letter usually has a variety of appearances when looked at in detail,” possibly an attempt by the printer to create “a more ‘genuine’ – i.e. traditional, ‘manuscript’ – look.”

It would have been important back then to make printed books look hand-copied, since not so long before, all books were hand-copied by definition. With the first Gutenberg Bible still less than half a century old, early printers had to make sure their relatively inexpensive books didn’t look like low-quality substitutes for the “real thing”; hence the assurances about both the type and the price in the text of Caxton’s advertisement. That the origin of advertising turns out to be closely connected with religion may come as a surprise — though given the fact that the print revolution itself began with a Bible, a product that in either physical or digital form now practically sells itself, it may not be that big a surprise.

If you would like to sign up for Open Culture’s free email newsletter, please find it here. It’s a great way to see our new posts, all bundled in one email, each day.

If you would like to support the mission of Open Culture, consider making a donation to our site. It’s hard to rely 100% on ads, and your contributions will help us continue providing the best free cultural and educational materials to learners everywhere. You can contribute through PayPal, Patreon, and Venmo (@openculture). Thanks!

via medievalbooks

Related Content:

Oxford University Presents the 550-Year-Old Gutenberg Bible in Spectacular, High-Res Detail

One of World’s Oldest Books Printed in Multi-Color Now Opened & Digitized for the First Time

Watch the First Commercial Ever Shown on American TV, 1941

Sell & Spin: The History of Advertising, Narrated by Dick Cavett (1999)

Based in Seoul, Colin Marshall writes and broadcasts on cities, language, and culture. His projects include the book The Stateless City: a Walk through 21st-Century Los Angeles and the video series The City in Cinema. Follow him on Twitter at @colinmarshall or on Facebook.

Leave a Reply