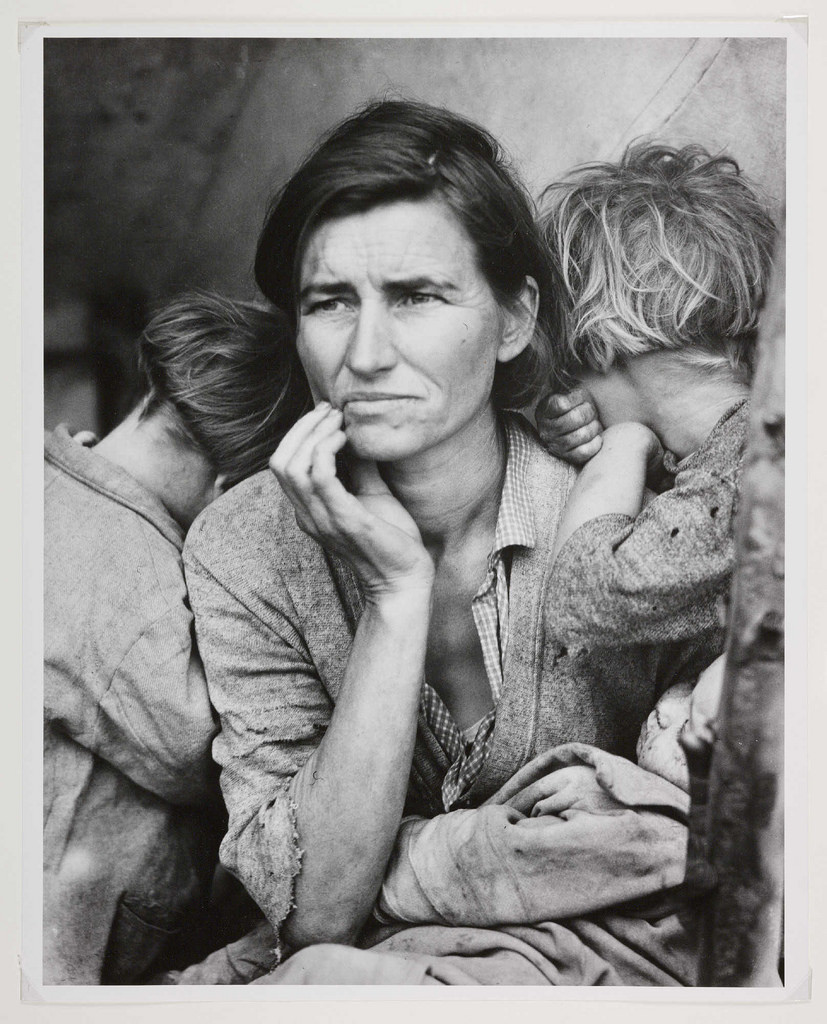

When we visualize the Great Depression, we think first of one woman: Native American migrant worker Florence Owens Thompson. Few of us know her name, though nearly all of us know her face. For that we have another woman to thank: the photographer Dorothea Lange who during the Depression was working for the United States federal government, specifically the Farm Security Administration, on “a project that would involve documenting poor rural workers in a propaganda effort to elicit political support for government aid.”

That’s how Evan Puschak, better known as the Nerdwriter, puts it in a video essay on Lange’s famous 1936 photo of Thompson, Migrant Mother. (For best results, view the video below on a phone or tablet rather than on a standard computer screen.) Reaching the migrant workers’ camp in Nipomo, California where Thompson and her children were staying toward the end of another long day of photography, Lange at first passed it by.

Only about twenty miles later did she decide to turn the car around and see what material the 2,500 to 3,500 “pea pickers” there might offer. She stayed only ten minutes, but in that time captured what Puschak calls the photograph that “came to define the Depression in the American consciousness” — it even heads the Great Depression’s Wikipedia page — and “became the archetypal image of struggling families in any era.”

Over time, Migrant Mother has also become “one of the most iconic pictures in the history of photography.” But Lange didn’t get it right away: it was actually the sixth portrait she took of Thompson, each one more powerful (and more able to “evoke sympathy from voters that would translate into political support”) than the last. Puschak takes us through each of these, marking the changes in composition that led to the photograph we can all call to mind immediately. “A lesser photographer would have milked the children’s faces for their sympathetic potential,” for instance, but having them turn away “communicates that message of family” without “taking away from the central face, or the eyes, which seem at last to let down their guard as they search the distance and worry.”

These and other actively made choices (including the removal of Thompson’s distracting left thumb in the darkroom) mean that “there is very little spontaneous in this iconic image of so-called documentary photography,” but “whether that diminishes its power is up to you. For me, being able to actually see the steps of Lange’s craft enhances her work.” Whatever Lange’s process, the product defined an era, and upon publication convinced the government to send 20,000 pounds of food to Nipomo — though by that point Thompson herself, who ultimately succeeded in providing for her family and lived to the age of 80, had moved on.

Related Content:

478 Dorothea Lange Photographs Poignantly Document the Internment of the Japanese During WWII

Yale Launches an Archive of 170,000 Photographs Documenting the Great Depression

Found: Lost Great Depression Photos Capturing Hard Times on Farms, and in Town

Edward Hopper’s Iconic Painting Nighthawks Explained in a 7‑Minute Video Introduction

Based in Seoul, Colin Marshall writes and broadcasts on cities, language, and culture. His projects include the book The Stateless City: a Walk through 21st-Century Los Angeles and the video series The City in Cinema. Follow him on Twitter at @colinmarshall or on Facebook.

You have an extra comma in the title.

We live near Nipomo, CA and was just wondering if a road that traverses Nipomo from south to north is named after Florence? It is Thompson Road. It is the local Hwy 1/101. Thanks.

Yeah, here’s what the subject had to say:

“I wish she [Lange] hadn’t taken my picture. I can’t get a penny out of it. She didn’t ask my name. She said she wouldn’t sell the pictures. She said she’d send me a copy. She never did.”

https://www.takimag.com/article/steinbecks_dust_bowl_gnomes_kathy_shaidle/

That in the story Migrant Mother has also become one of the most iconic pictures in the history of photography.

In the story These and other active made choices.