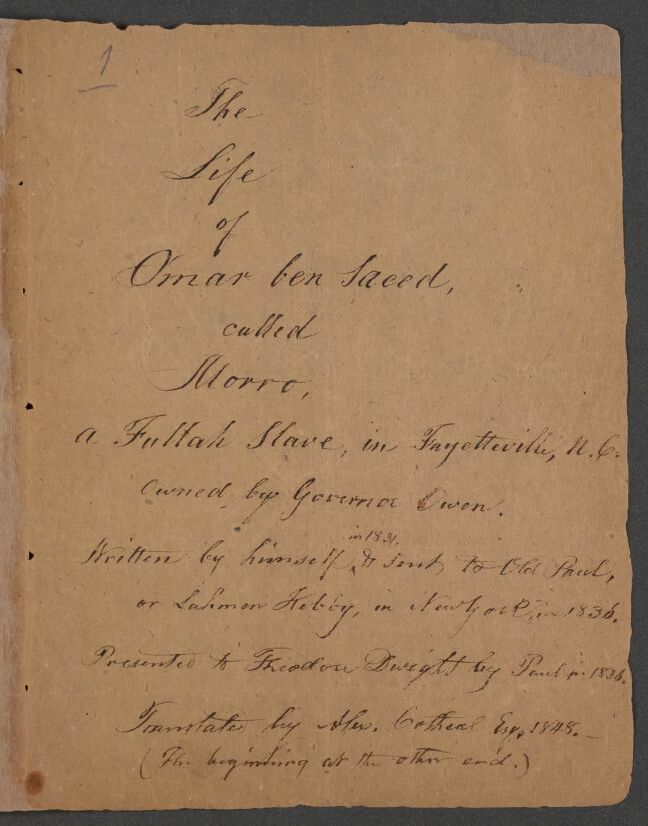

Several important pieces of primary documentary evidence have now become freely available to scholars, students, and anyone interested in the history of American slavery, one an autobiography written in Arabic by Omar Ibn Said, an enslaved Muslim man who was actively encouraged to read and write by his North Carolina owners. The Library of Congress announced this month that it had acquired the 1831 manuscript in 2017 and has now uploaded digital scans of Said’s Arabic original and several other documents about him and in his hand.

A 1925 English translation of Said’s short memoir appeared in The American Historical Review as “the first story of an educated Mohammedan slave in America.” Since 2013, it has been available online at the University of North Carolina’s Documenting the American South project.

It is a confusing document, in English at least: fragmented not only in its style but also in its shifting identifications. This is hardly surprising given Said’s story, both a common and very uncommon one.

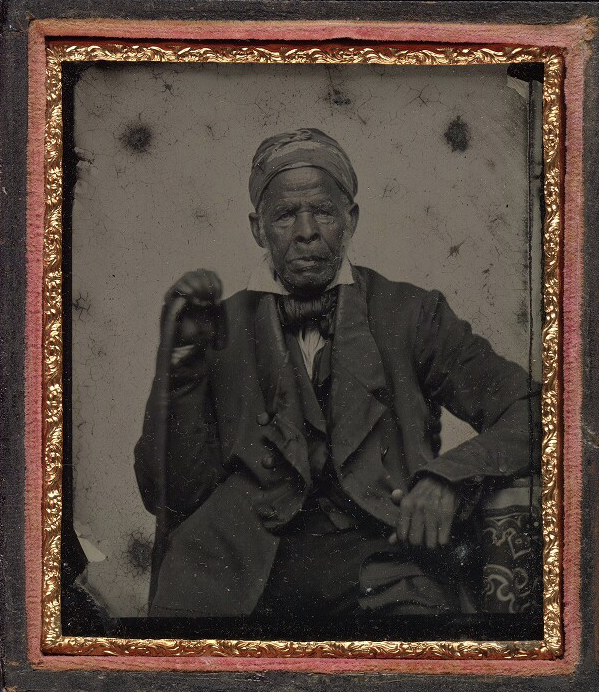

Like millions of Africans, Said had been captured and enslaved, brought to Charleston, South Carolina in 1807, escaped, then been captured, jailed, and enslaved again in North Carolina. What made him a minorly famous figure in his own time—variously known as “Uncle Moreau” (or just “Morro” or “Moro”) and Prince Omeroh—as well as an important historical figure in ours, was that his is the only known surviving account in Arabic. It is one written, moreover, by a man who had been a writer and Islamic scholar for 25 years before his enslavement in what is now Senegal.

Said “gives a brief sketch of his life in Africa,” in the 15-page autobiography, the Library of Congress notes, “but enough to create a portrait of a highly educated and well-to-do individual.” His learning and literary talents so impressed his owner James Owen, brother of North Carolina governor John Owen, that he was given an English Qu’ran, “in the hope that he might pick up the language,” writes Brigit Katz at Smithsonian. He was also given an Arabic Bible. “In 1821, Said was baptized.”

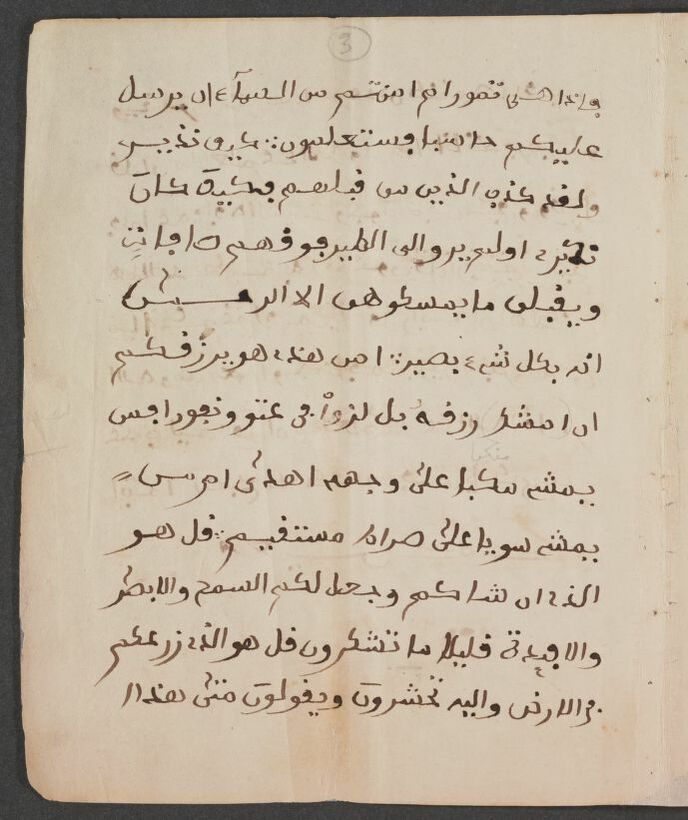

He became “an object of fascination to white Americans,” after converting to Christianity, “but he does not appear to have forsaken his Muslim religion.” Said praises his owner copiously in the sketch of his life, with many expressions of Christian piety. He also opens his text, which is addressed to a “Sheikh Hunter,” with several verses quoted from the Qu’ran. “These might be omitted as not autobiographical,” the 1925 translator wrote, “though it has been thought best to print the whole.”

To the contrary, these verses, claims Mary-Jane Deeb—chief of the Library’s African and Middle Eastern Division—tell us quite a lot about Said, perhaps as much as the main text itself. They can be seen as a subversive means of communicating his continued Islamic faith and his continued resistance to his enslavement. The Surah he chose to quote “is extremely important. It’s a fundamental criticism of the right to own another human being.”

Said also inscribed in his Arabic Bible the phrases “Praise be to Allah, or God” and “All good is from Allah.” The North Carolina Department of Cultural Resources notes that “fourteen Arabic manuscripts in Umar’s hand are extant. Many of them include excerpts from the Qu’ran and references to Allah.” It’s possible that Said’s conversion was genuine, and that he still expressed himself in the idiom of his former religion and subject of long study. It’s also quite likely that, for all the freedom he received to study and write, he still had plenty of good reasons to fear openly resisting the identity forced upon him.

Said died in 1864, Katz notes, “one year before the U.S. legally abolished slavery. He had been in America for more than 50 years. Said was reportedly treated relatively well in the Owen household, but he died a slave,” having “much forgotten” as he writes in his autobiography “my own, as well as the Arabic language,” holding on to what he remembered of his language and his faith by writing down what he recalled from memory. View the digitized documents from the Omar Ibn Said Collection at the Library of Congress and learn much more about his life at UNC’s Documenting the American South.

Related Content:

Josh Jones is a writer and musician based in Durham, NC. Follow him at @jdmagness

Awesome

Wow! MashAllah! That’s a wonderful discovery. I’m a Latina Muslim and I always loved to learn about African American history. I always had a feeling that some of the slaves that were brought over during that time some were Muslim but were then forced to Christianity or forget who they were (their native language, culture, etc) . Glad people now can learn about him. May he Rest In Peace . Respect.

Is there any books written about him or by him at libraries

Thanks!

There are over 500 pages of writings in Arabic from Omar ibn Said and other writers, so saying it is the only Arabic is a stretch. It is the only extant autobiography in Arabic. See my Five Classic Muslim Slave Narratives for more details.

https://www.amazon.com/Classic-Narratives-American-Islamic-Heritage/dp/1463593279

See my https://www.amazon.com/Classic-Narratives-American-Islamic-Heritage/dp/1463593279 for more details on Omar ibn Said and other Muslims in Antebellum America.

Try my Five Classic Muslim Slave Narratives.

Amazing!

The text is in Maghrebi-Andalusian Arabic and it shows a clear influence from North African Sunni Islam. This man was a cleric who knew Quran and Islamic jurisprudence.