It’s a perverse irony or an apt metaphor: Leonard Cohen is best known for a song that took him five years to write, and that went almost unheard on its debut, in part because the head of Columbia’s music division, Walter Yetnikoff, refused to release Cohen’s 1985 album Various Positions in the U.S. “Leonard, we know you’re great,” said Yetnikoff, “We just don’t know if you’re any good.” It might have been Cohen’s summation of life itself.

It wasn’t until Jeff Buckley’s electric gospel cover in 1994 (itself a take on John Cale’s version) that “Hallelujah” became the massive hit it is, having now been covered by over 300 artists. Canadian magazine Maclean’s has called the song “pop music’s closest thing to a sacred text.” One can imagine Cohen looking deep into the eyes of those who think that “Hallelujah” is a hymn of praise and saying, “you don’t really care for music, do ya?”

With the trappings and imagery of gospel, and a sleazy synth-driven groove, it tells a story of being tied to a chair and overpowered, kept at an emotional distance, learning how to “shoot somebody who outdrew ya.” Love, sings Cohen sings in his lounge-lizard voice, “is not a victory march… It’s not somebody who’s seen the light.” If you’re looking to Leonard Cohen for redemption, best look elsewhere.

Used in film and television for moments of epiphany, triumph, grief, and relief, “Hallelujah,” like all of Cohen’s work, makes profane and prophetic utterances in which beauty and ugliness always coexist, in a painful arrangement no one gets clear of. Cohen will not let us choose between darkness and light. We must take both.

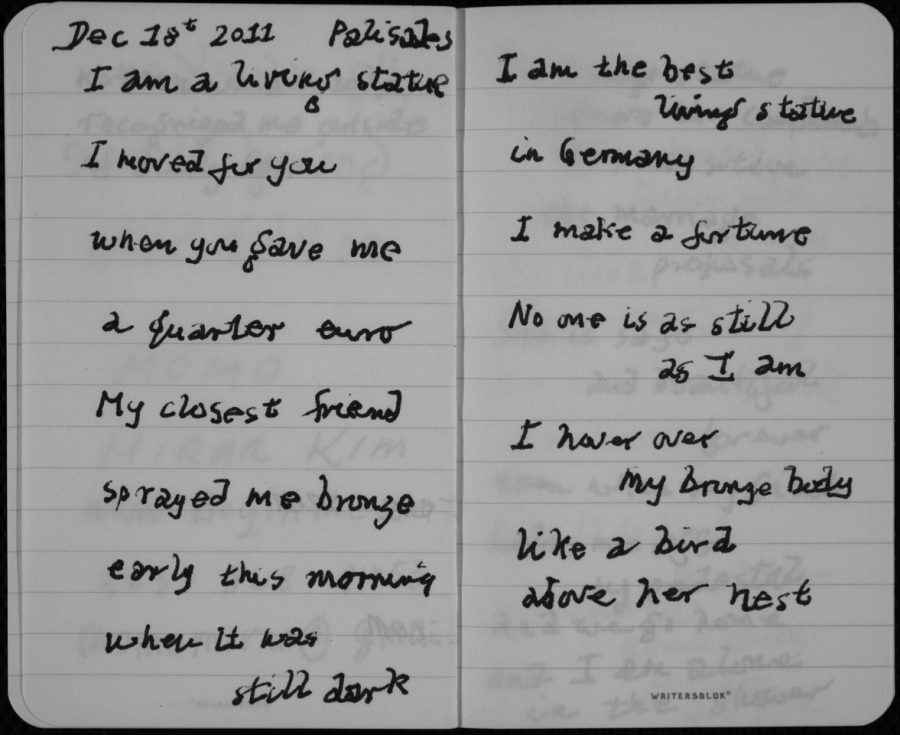

In the last years of his life, he brought his tragic vision to a remarkable climax in his final, 2016 album, You Want it Darker. Last month, the final act in his magisterial career premiered in the form of The Flame. The book is “a collection of poems, lyrics, drawings, and pages from his notebooks,” writes The Paris Review, who quote from Cohen’s son Adam’s forward: “This volume contains my father’s final efforts as a poet…. It was what he was staying alive to do, his sole breathing purpose at the end.”

Cohen did not leave words of hope behind. One of his last poems issues forth an enigmatic and terrifying prophecy, hammering away at the conceits of human power.

What is coming

ten million people

in the street cannot stop

What is coming

the American Armed Forces

cannot control

the President

of the United States

and his counselors

cannot conceive

initiate

command

or direct

everything

you do

or refrain from doing

will bring us

to the same place

the place we don’t know

your anger against the war

your horror of death

your calm strategies

your bold plans

to rearrange

the middle east

to overthrow the dollar

to establish

the 4th Reich

to live forever

to silence the Jews

to order the cosmos

to tidy up your life

to improve religion

they count for nothing

you have no understanding

of the consequences

of what you do

oh and one more thing

you aren’t going to like

what comes after

America

But The Flame is not all jeremiad. In some ways it’s a turn from the grim, oracular voice of “You Want it Darker” and to a more intimate, at times quotidian and confessional, Cohen. “All sides of the man are present” in this book of poems and sketches writes Scott Timberg at The Guardian. “Was he, in the end, a musician or a poet? A grave philosopher or a grim sort of comedian? A cosmopolitan lady’s man or a profound, ascetic seeker? Jew or Buddhist? Hedonist or hermit?” Yes.

Cohen’s work, his son says, “was a mandate from God.” The writing of his final poems “was all private.” “My father was very interested in preserving the magic of his process. And moreover, not demystifying it. Speaking of any of this is a transgression.”

However else we interpret Leonard Cohen’s theo-mythic-philosophical incantations, he made a few things clear. What he meant by “God” was deeper and darker than what most people do. And to trivialize the mysteries of life and love and death and song, to pretend we understand them, he suggests, is a grave and tragic, but perhaps inevitable, mistake. “You want it darker,” he sang at the end. “We kill the flame.”

via The Paris Review

Related Content:

Young Leonard Cohen Reads His Poetry in 1966 (Before His Days as a Musician Began)

How Leonard Cohen Wrote a Love Song

Josh Jones is a writer and musician based in Durham, NC. Follow him at @jdmagness

the poem is from 2003, so certainly not “one of his last”…?