Book historians and rare manuscript librarians do not have the most glamorous jobs by the usual standards. They deal with weathered, tattered, fragmentary scraps of text in archaic languages and lettering. It’s work unlikely to receive the Hollywood (or Netflix) treatment unless wizards, witches, or occult detectives are involved. But the relative obscurity of these professions does not make the work any less valuable. Without dedicated archivists and preservationists, a slow collective amnesia, or worse, can set in.

One might call this attitude precious. Specialists are useful, art is great, but with sophisticated machine learning, we can make, store, and print copies of every historical artifact in the world, along with all of the accumulated knowledge about them. What need to dote on crumbling manuscripts? Why the special status of the original? The question, taken up by Walter Benjamin in his 1936 essay, “The Work of Art in the Age of Mechanical Reproduction,” comes down in part to something he called “aura.”

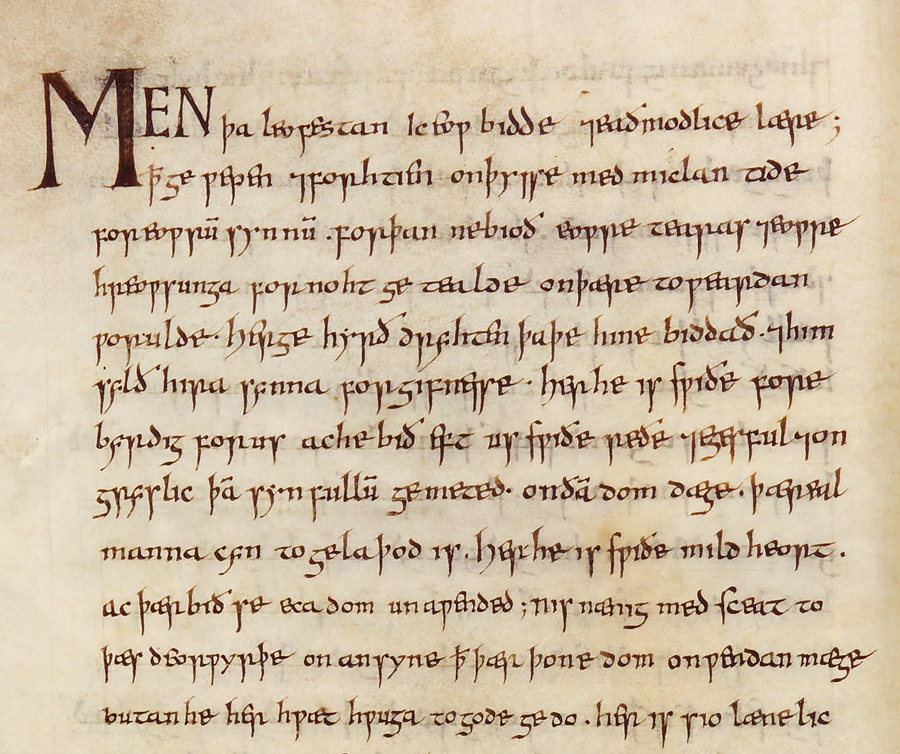

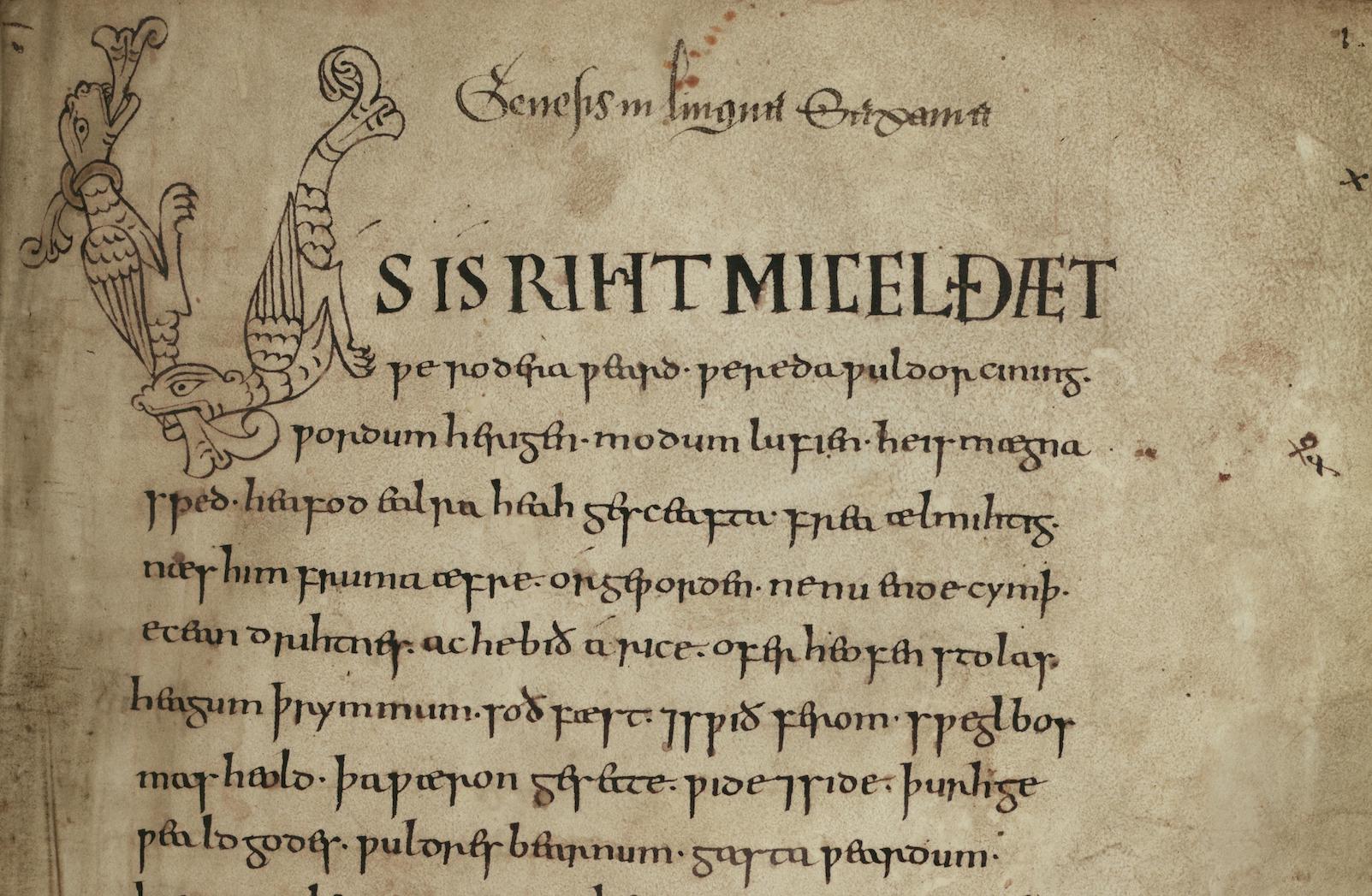

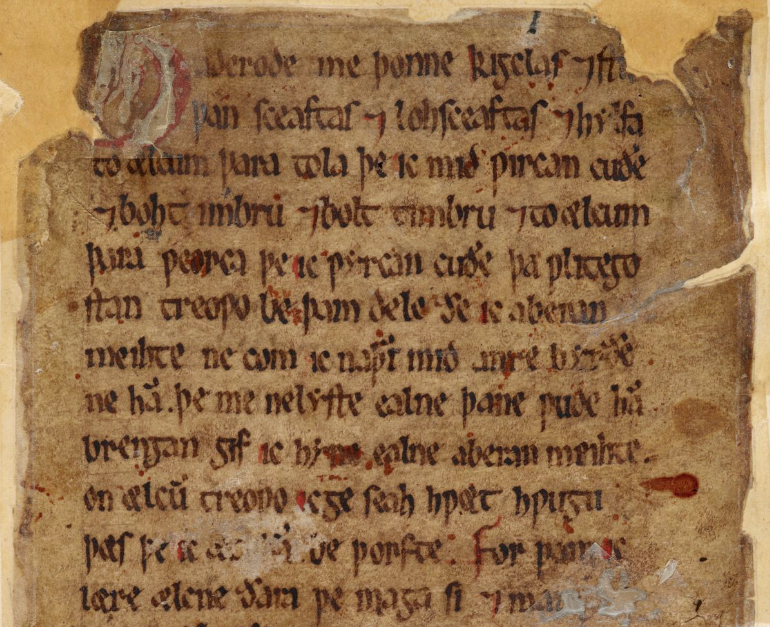

Take the case of four manuscripts, all of which recently appeared together at the British Library’s extensive exhibition Anglo-Saxon Kingdoms: Art, Word, War: The Vercelli Book, the Junius Manuscript, the Exeter Book, and the Beowulf Manuscript contain riddles, religious texts, elegies, and the oldest manuscript of the oldest known poem in English. These represent the sum total of extant original literary manuscripts in Old English, a tongue several centuries distant from our own but still embedded deep within the structure of every modern version of the language.

Each manuscript has what, as Benjamin wrote, “even the most perfect reproduction of a work of art is lacking… its presence in time and space, its unique existence at the place where it happens to be.” Josephine Livingstone puts the matter more plainly at The New Republic.

Why are these four books so special? It has to do, I think, with the concept of the original—a concept we have almost entirely lost touch with. The Beowulf Manuscript… is not merely a representation of a story; it is the story…. The manuscripts confront us with a former version of our literary selves; identities that we barely recognize, and which estrange us from ourselves.

We can reproduce history infinitely, but the only way to experience the humbling otherworldliness that dwarfs our cramped ideas about it is through its physical remainders. Livingstone doesn’t clarify whom she includes in the phrase “our literary selves,” but we might as well say, at minimum, this means every speaker of English and everyone who has read English literature in translation or felt the influence of English words and phrases in other languages.

We acquire the language we hear and read from literary sources, however remote; they are constitutive, the threads that weave together cultural narratives into a larger pattern. The original work of art, Benjamin argued, like the relic, has religious significance. And where the relic grounds the cult, art grounds material culture in such a way, he thought, that it repels fascism’s aesthetic obsession with destruction.

Original artifacts “must restore the instinctual power of the human bodily senses,” literary scholar Susan Buck-Morss elaborates, “for the sake of humanity’s self-preservation.” The statement may sound less grandiose in the context of Europe in 1936, or we might consider it just as relevant today (and expand it to include not only art but nature).

We can rely on the fact that, should the Beowulf Manuscript be destroyed, Livingstone grants, “the poem would still survive,” as would the image of the manuscript in very fine detail. That is “the hope contained in Benjamin’s dirge.” But what is lost can never appear in the world again. You can view most of these rare texts—The Vercelli Book, the Junius Manuscript, and the Beowulf Manuscript—in high resolution scans at the British and Bodleian Libraries.

The texts are a minuscule sampling of the number of cultural artifacts around the world worthy of preservation, and publicity. And they are a tiny sampling of the literary production of Old English. But on them rests a great deal of our understanding about the linguistic ancestors of the language, with more to learn, perhaps, as scanning technology becomes even more advanced, illuminating rather than replacing the original.

Related Content:

1,000-Year-Old Manuscript of Beowulf Digitized and Now Online

Europe’s Oldest Intact Book Was Preserved and Found in the Coffin of a Saint

Josh Jones is a writer and musician based in Durham, NC. Follow him at @jdmagness

These four manuscripts “represent the sum total of extant original literary manuscripts in Old English” only if we define “literary” as “poetry” (and even then, there is poetry outside these four books). Prose texts like Apollonius of Tyre, the Wonders of the East, saints’ lives, the Anglo-Saxon Chronicle, and translations of philosophical and theological works inhabited the same world as the poetic manuscripts, in the absence of a category of “literature” as we would mark it today.

How did you figure out what the text said?

With all due respect, it is kind of delusion.

Yes, these 4 mss contain almost all of the *poetry* written in OE. There are many other mss that contain OE prose on various topics.

There are also other manuscripts that contain Old English poems, even. There are many mistakes in this article that even a basic Wikipedia search could have prevented.