Plot, setting, character… we learn to think of these as discrete elements in literary writing, comparable to the strategy, board, and pieces of a chess game. But what if this scheme doesn’t quite work? What about when the setting is a character? There are many literary works named and well-known for the unforgettable places they introduce: Walden, Wuthering Heights, Howards End…. There are invented domains that seem more real to readers than reality: Faulkner’s Yoknapatowpha, Thomas Hardy’s Wessex… There are works that describe impossible places so vividly we believe in their existence against all reason: Italo Calvino’s Invisible Cities, China Miéville’s The City and the City, Jorge Luis Borges’ “Tlön, Uqbar, Orbis Tertius”….

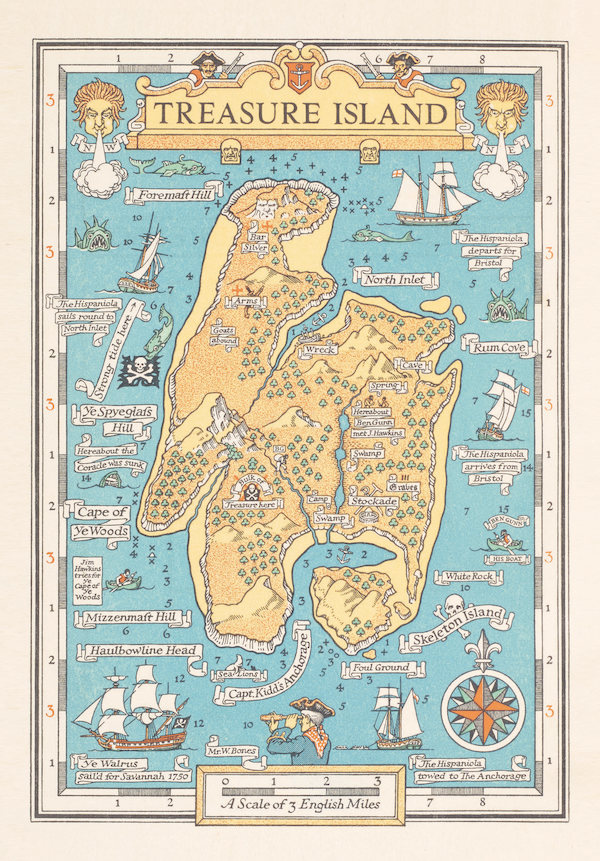

What sustains our belief in the integrity of fictional places? The fact that they seem to act upon events as much as the people who live in them, for one thing. And, just as often, the fact that so many authors and illustrators draw elaborate maps of literary settings, making their features real to us and embedding them in our minds.

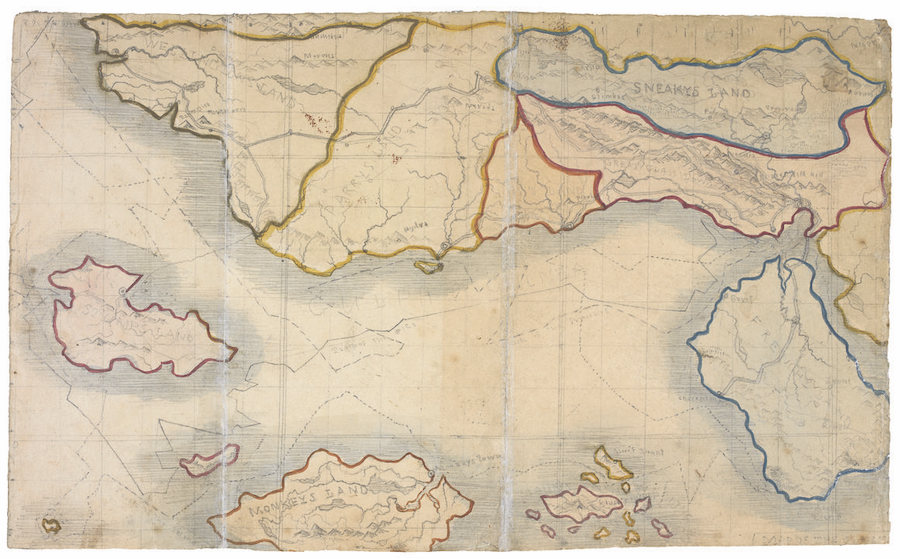

A new book, The Writer’s Map, edited by Huw Lewis-Jones, offers lovers of literary maps—whether in non-fiction, realism, or fantasy—the opportunity to pore over maps of Thomas More’s Utopia (said to be the first literary map), Robert Louis Stevenson’s Treasure Island, J.R.R Tolkien’s Middle Earth, Branwell Brontë’s Verdopolis (above), and so many more.

The book is filled with essays about literary mapping by writers and map-makers, and it touches on the way authors themselves view imaginative mapping. “For some writers making a map is absolutely central to the craft of shaping and telling their tale,” writes Lewis-Jones. For others, making maps is also a way to avoid the painful task of writing, which Philip Pullman calls “a matter of sullen toil.” Drawing, on the other hand, he says, “is pure joy. Drawing a map to go with a story is messing around, with the added fun of coloring it in.” David Mitchell agrees: “As long as I was busy dreaming of topography,” he says of his maps, “I didn’t have to get my hands dirty with the mechanics of plot and character.”

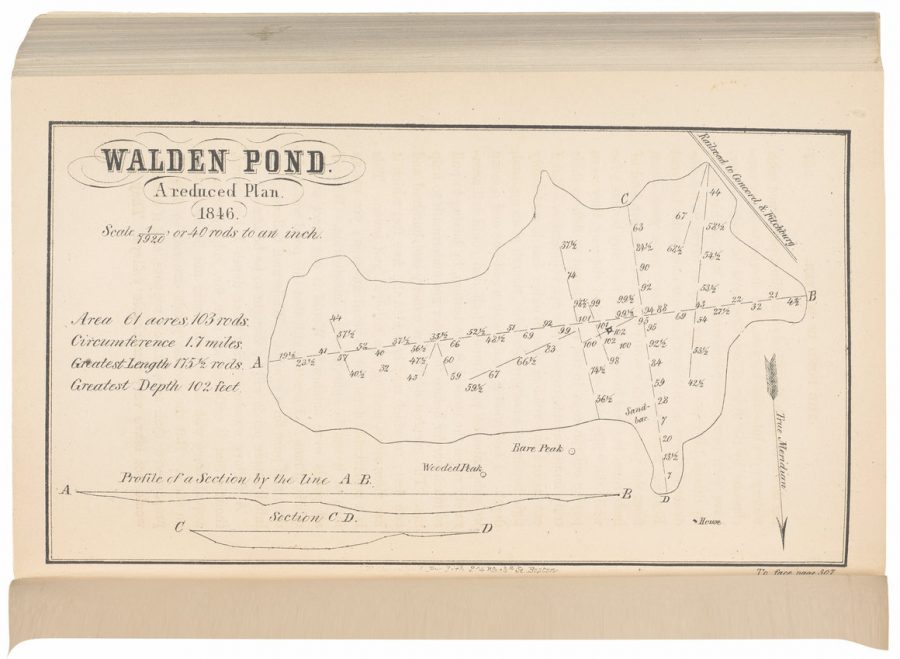

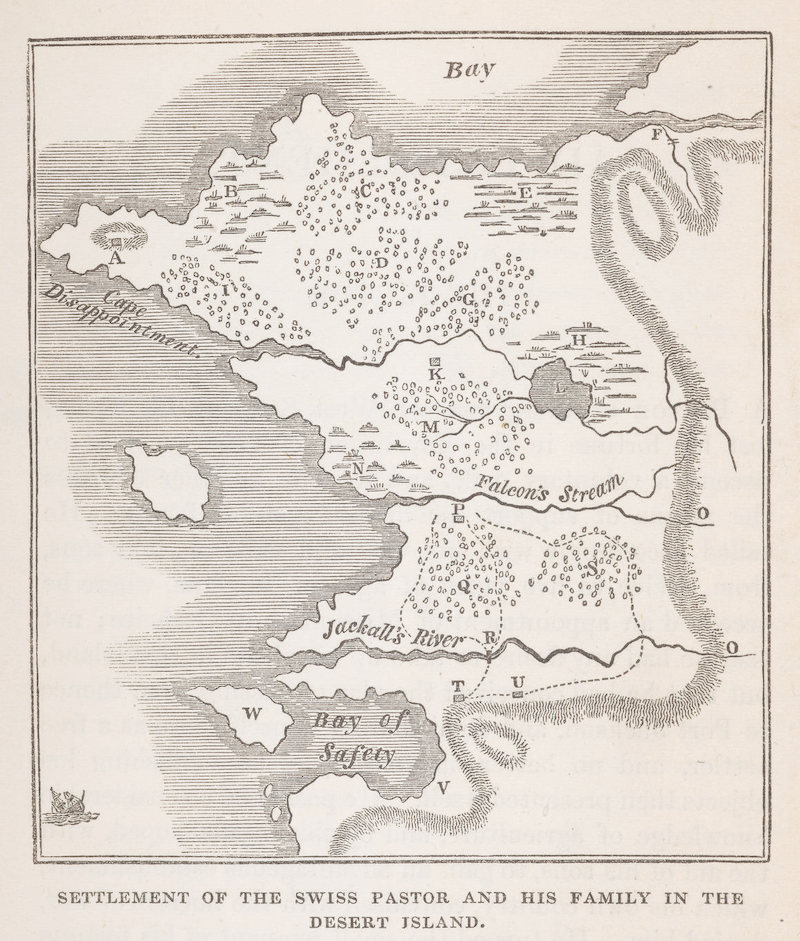

It may surprise you to hear that writers hate to write, but writers are people, after all, and most people find writing tedious and difficult in some part. What all of the writers featured in this collection share is that they love indulging their imaginations, making real their lucid dreams, whether through the diversion of drawing maps or the grind of grammar and syntax. Many of these maps, like Thoreau’s drawing of Walden Pond or Johann David Wyss’s illustration of the desert island in The Swiss Family Robinson, accompanied their books into publication. Many more remained secreted in authors’ notebooks.

There are many such “private treasures” in The Writer’s Map, notes Atlas Obscura: “J.R.R. Tolkien’s own sketch of Mordor, on graph paper; C.S. Lewis’s sketches; unpublished maps from the notebooks of David Mitchell… Jack Kerouac’s own route in On the Road….” Do we read a literary map differently when it wasn’t meant for us? Can maps be sly acts of misdirection as well as whimsical visual aids? Should we treat them as paratextual and unnecessary, or are they central, when an author chooses to include them, to our understanding of a story? Such questions, and many, many more, are taken up in The Writer’s Map, a long overdue survey of this longstanding literary tradition.

via Atlas Obscura

Related Content:

12 Classic Literary Road Trips in One Handy Interactive Map

Map of Middle-Earth Annotated by Tolkien Found in a Copy of Lord of the Rings

William Faulkner Draws Maps of Yoknapatawpha County, the Fictional Home of His Great Novels

Josh Jones is a writer and musician based in Durham, NC. Follow him at @jdmagness

Leave a Reply