Leonardo da Vinci was a man of many abilities, so many that he has defined the very image of the man of many abilities for more than 500 years now. History remembers him for his impressive intellectual feats of science and engineering (as well as the ambition of his to-do lists), but even more so for his works of visual art. Most of us get our introduction to Leonardo through images like the Mona Lisa, The Last Supper, and Vitruvian Man, not least because they’ve long since become too culturally prominent to avoid. The question of how on earth he did it naturally springs from contemplation of Leonardo’s whole body of work, but also from contemplation of many of the individual pieces that constitute it. A part of the answer, recent research suggests, may well have to do with a disability.

“There is now evidence that da Vinci’s renowned capacity to reproduce the three-dimensional world in paintings may have been aided by an eye disorder that allowed him to see in both 2‑D and 3‑D, according to a study published Thursday in JAMA Opthalmology, a peer-reviewed journal,” writes The Washington Post’s Allyson Chiu.

“Da Vinci is believed to have had a condition called intermittent exotropia, a form of strabismus, commonly referred to as being ‘walleyed’,” a form of an eye misalignment. If he did, it would have hampered his depth perception enough for him to see a flatter world than the one most everyone else does, and thus a world more suited to faithful replication on the page or the canvas.

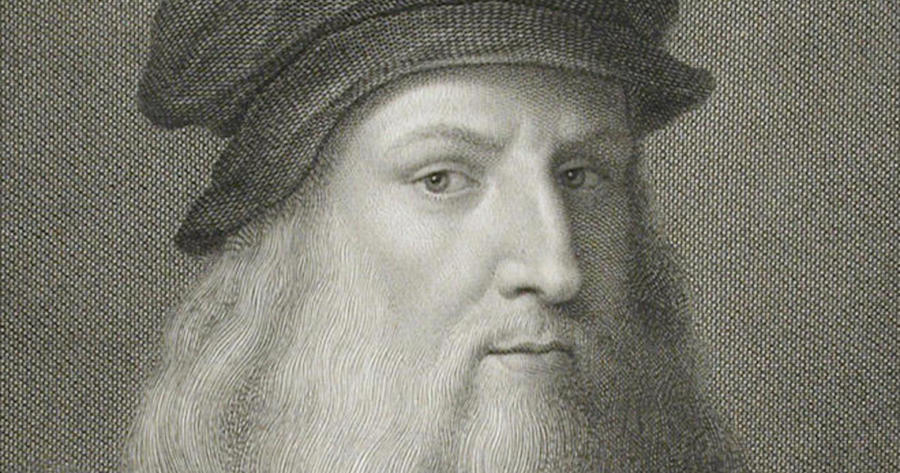

But the fact Leonardo that could sometimes control his eyes enough to get them into proper alignment, says the study’s author Christopher Tyler, would make him “very aware of the 3‑D and 2‑D depth cues and the difference between them.” He came to suspect that Leonardo suffered from exotropia — if “suffered” is quite the right word here — after noticing the alignment of the eyes in both images considered portraits of the man himself as well as the portraits Leonardo made of others (on the theory that the work of an artist will, to an extent, reflect his own characteristics). The ophthalmologically inclined can judge for themselves by reading Tyler’s paper online. And if other, similar studies done in the past also hold up, Leonardo isn’t alone in art history: such figures as Rembrandt, Picasso, and Degas have also left behind evidence of their possibly strabismic vision. We sometimes say that artists see the world differently; the greatest artists may take that saying to a new level of literalness.

Related Content:

Leonardo da Vinci’s Visionary Notebooks Now Online: Browse 570 Digitized Pages

The Anatomical Drawings of Renaissance Man, Leonardo da Vinci

Leonardo da Vinci’s Bizarre Caricatures & Monster Drawings

What Leonardo da Vinci Really Looked Like

Based in Seoul, Colin Marshall writes and broadcasts on cities, language, and culture. His projects include the book The Stateless City: a Walk through 21st-Century Los Angeles and the video series The City in Cinema. Follow him on Twitter at @colinmarshall or on Facebook.

Leave a Reply