Few things connect the electronic music of the 90s to that of today like Aphex Twin. The long career of Richard D. James—he of the sinister grinning face plastered on buxom models and a gang of violent children in his early NSFW videos—anticipated and in some ways invented the glitchy, clattering, squelching, cacophonous, alien sound of the digital 21st century. The release of his entire catalog, including several unreleased tracks, on his website to buy or stream for free shows his clear awareness of how seminal his music has been for over three decades.

James became a crossover superstar in the late 90s, grew irritated with imitators, got lumped in with so-called IDM (“intelligent dance music”), and threatened retirement many times. Then he did retire the Aphex Twin name in 2001 after releasing Drukqs and making music for the next few years under other monikers. He also claimed he’d never release his most innovative music “because I don’t want people ripping me off.”

In the meanwhile, a couple or so major global economic changes came about, new younger fans came of age, and bedroom producers armed with laptops instead of the battery of synthesizers James commanded sprang up around the world. It might have seemed—as it did for a number of people who grew up making, buying, and dancing to electronic music at the end of the 20th century—that it was time to pass the baton to another rave generation.

Instead, James returned in 2014—after his infamous logo popped up on NYC sidewalks—with a new album, Syro, a huge suite of songs that won Aphex Twin near-unanimous critical adoration and a Grammy. The hermetic musician had previously summed up his relationship with his audience by telling an interviewer he hated them. He appeared to hate the press even more. Returning thirteen years later as a 43-year-old father seemed to have mellowed him.

James is positively chatty in a lengthy Pitchfork interview. He begins by explaining the origin of the word “syro.” It came from his son, who “doesn’t know what it means, either. But it means something. And it sounds cool.” He might have been talking about the titles of nearly every track on the album, his latest EP, or his retirement album, Druqks.

For James, a blanket contempt for the status quo manifests in scramblings of sense and sound. Syro’s only decipherable title, “minipops 67 [120.2] [source field mix],” may or may not refer to the 1983 British children’s show featuring preteens singing contemporary pop songs while dressed up like the original performers. Could be a pisstaking nod to his generation or an earnest visit to childhood memories through the portal of his own kids’ nonsense word, or both.

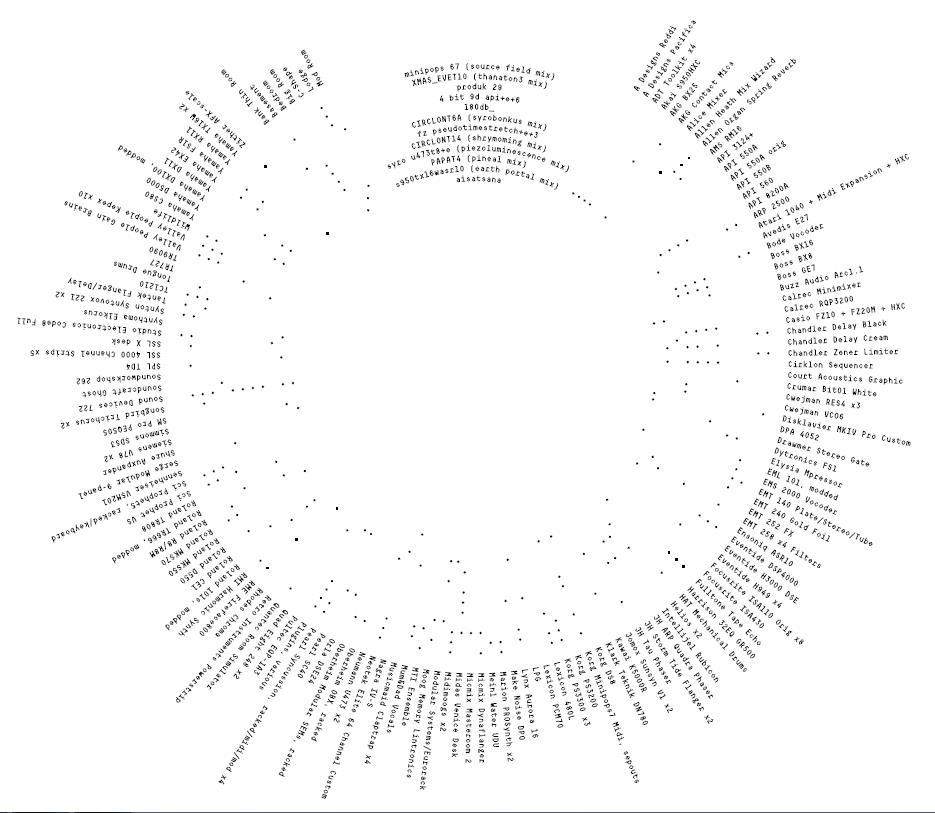

The Aphex Twin comeback saw James opening up about his process in interviews and releasing a list of synth instruments used on Syro in the form of a dense infographic, above. (The dots in concentric circles “line up with the track list,” notes Synthtopia, “so they graphically indicate the gear that was used on each track.”). These gestures to his fans presaged the release of his entire catalog for streaming on his site, “a near-complete collection of James recording output since 1991,” as Ars Technica writes, including “hours of previously unreleased material from pretty much every phase of his career.”

Check out the site here to stream Aphex Twin’s recorded output in chronological or random order, buy each track in a number of formats, including the unreleased rarities, and read the extensive Aphex Twin interview at Pitchfork, a conversation that sees him musing on abandoning all previous human influences and making music from outer space.

Related Content:

The 50 Best Ambient Albums of All Time: A Playlist Curated by Pitchfork

Josh Jones is a writer and musician based in Durham, NC. Follow him at @jdmagness

UNUSUAL BOX LOVE A.T. ! THANKS

Minipops is a reference to the Korg Minipops which he uses all over this album (at least if I’m reading the gear chart at the bottom correctly).