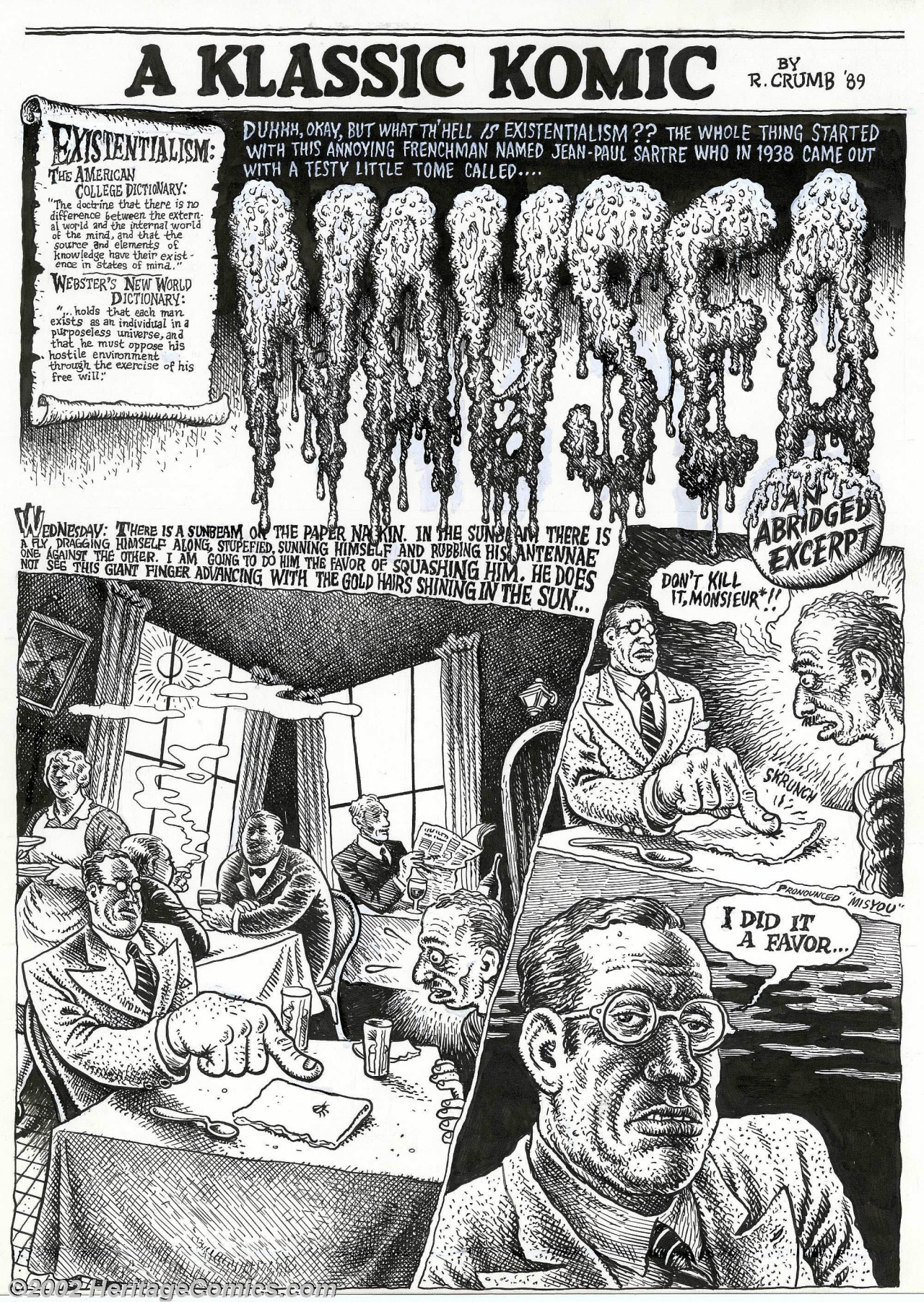

Sartre’s novel Nausea introduced his philosophical view as a form of illness to a WWII readership. “Nausea is existence revealing itself—and experience is not pleasant to see,” he wrote in his own summary of his first book, published in 1938. The novel’s dramatization of Historian Roquentin’ s crisis presents a case of existential sickness as mostly involuntary.

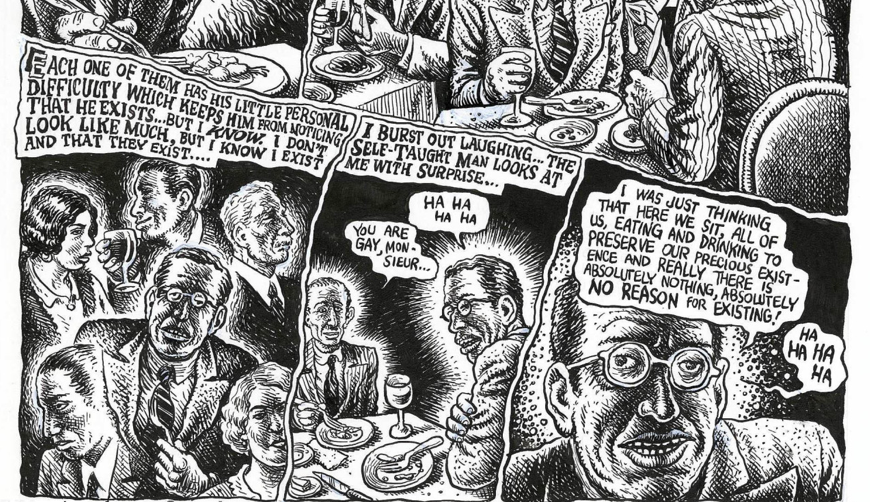

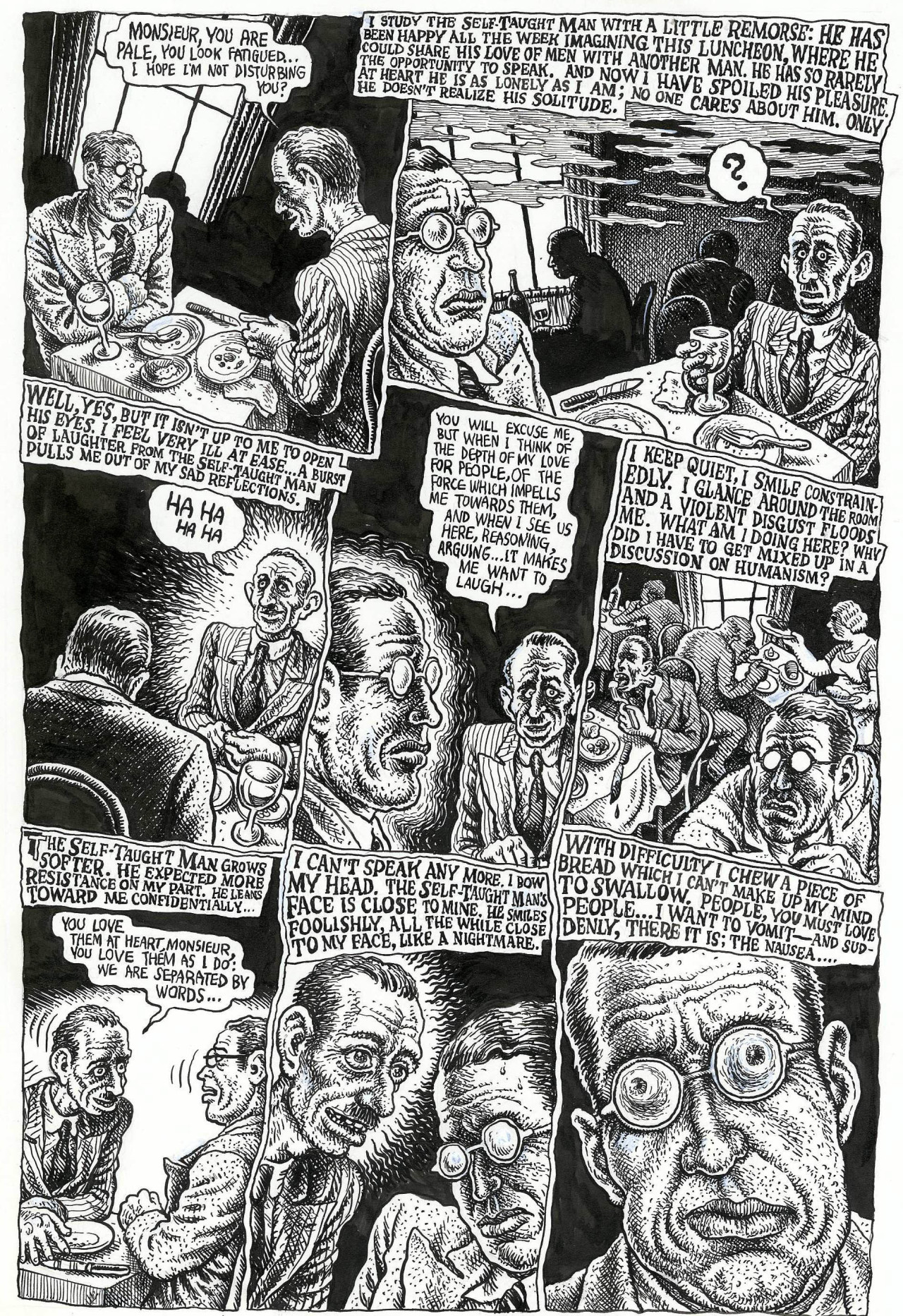

Though published before his many Marxist books and essays, Nausea connects the malaise to a certain class experience. “I have no troubles,” thinks Roquentin in Robert Crumb’s short adaptation of the book above, “I have money like a capitalist, no boss, no wife, no children; I exist, that’s all…. And that trouble is so vague, so metaphysical that I am ashamed of it.” Nausea, in one sense, is bourgeoise alienation, while Roquentin’s conversation partner, the Self-Taught Man, confesses a naïve humanist idealism.

The characters alone, some critics suggest, imbue the book with a subtle parody. As he listens to the Self-Taught Man’s troubles and ruminates on his own, Crumb’s Roquentin grows more Sartre-like. Significantly, the Self-Taught Man takes on a Crumb-like demeanor and aspect. Their dialogue moves briskly, the scene resembling My Dinner with Andre with less banter and more neurosis. Sartre’s tone lends itself well to Crumb’s obsessive, tightly-composed panels.

Crumb’s literary interpretations have gravitated toward other anxious writers like Charles Bukowski and Franz Kafka, as well as the murder and incest of the book of Genesis. The underground comics legend is right at home with Sartrean dread and despair. Crumb became famous for Fritz the Cat, an animated film version of his raunchy hipster, what many called his grossly sexist and racist sex fantasies, and the drawing and slogan “Keep on Truckin’.” He was a figure of 60s and 70s counterculture, but that’s never where he belonged.

Crumb was a Sartrean protagonist , even when he “often portrayed himself in his work as naked… and priapic.” In an an interview with Crumb The Guardian describes him:

his words are depressive and lugubrious, and yet he appears mellow, laughing easily through his existential nausea. The most terrible stories amuse him as much as they pain him. He tells me how a best friend killed himself by swallowing four bottles of paper correction fluid, and he chortles. He talks of his own despair, and giggles. He admits that he could never have imagined a life quite so fulfilled—with Aline, and his beloved daughter Sophie, also a cartoonist, and success and money—and says he’s still miserable as hell, and laughs.

He is a little Roquentin, a little bit Sartre, a little bit Self-Taught man, applying to his reading of literature and philosophy an LSD-assisted, sex-positive, and unavoidably controversial and depressive sensibility. See the full Crumb-illustrated Nausea here.

Related Content:

R. Crumb Describes How He Dropped LSD in the 60s & Instantly Discovered His Artistic Style

Josh Jones is a writer and musician based in Durham, NC. Follow him at @jdmagness

Leave a Reply