Photo via the British Library

If you’re a British history buff, next month is an ideal time to be in London for the British Library’s “once-in-a-generation exhibition” Anglo-Saxon Kingdoms: Art, Word, War, opening October 19th and featuring the illuminated Lindisfarne Gospels, Beowulf, Bede’s Ecclesiastical History, the “world-famous” Domesday Book, and Codex Amiatinus, a “giant Northumbrian Bible taken to Italy in 716” and returning to England for the first time in 1300 years. But with all of these manuscript stars stealing the show, one special exhibit might go overlooked, the St. Cuthbert Gospel, the oldest surviving intact European book.

A Latin copy of the Gospel of John, the book was originally called the Stonyhurst Gospel, after its first owner, Stonyhurst College. It acquired its current name because it was found inside the coffin of St. Cuthbert, a hermit monk who died in 687 and whose remains, legend has it, were incorruptible. This supposed miracle inspired a cult that placed offerings around Cuthbert’s tomb. Just when and how the small book made its way into his coffin remains a mystery. It was likely sometime between the 700s and 800s CE, when his body was moved to Durham due to Viking raids.

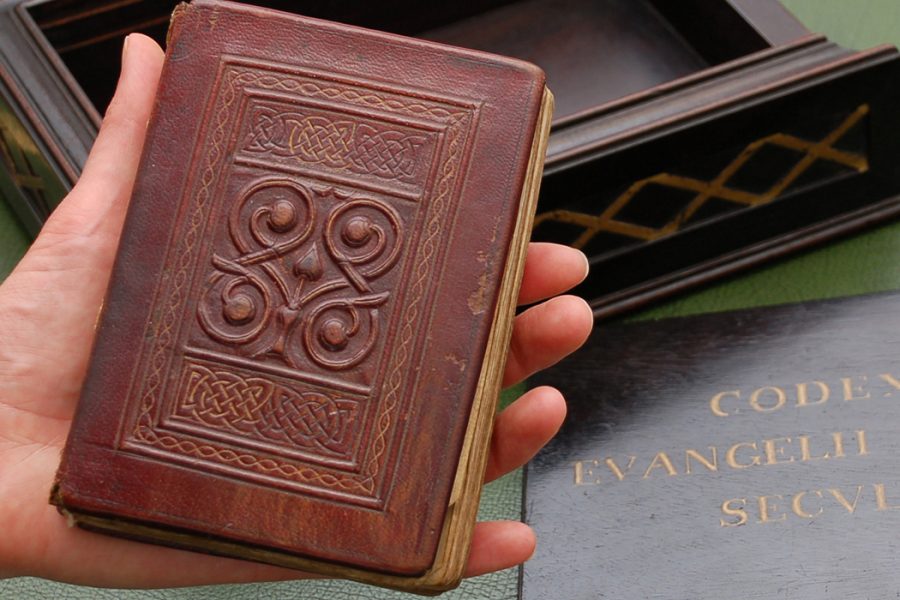

When Cuthbert’s casket was opened in 1104, the book was found “in miraculously perfect condition,” writes the British Library, inside “a satchel-like container of red leather with a badly-frayed sling made of silken threads.” Scholars have dated the book’s creation to between 700 and 730, and its interest for academics and lay people alike lies not only in the legend of St. Cuthbert but in the book’s physical qualities and its own uncorrupted nature. As Allison Meier writes at JSTOR Daily, “the 1,300-year-old manuscript retains its original pages and binding,” a remarkable fact for a book of its age.

Its condition makes it an “important example of Insular art, which was created on the British Isles and Ireland between 600 and 900 CE.” The general features of this style involve “the layering of pattern, line, and color on seemingly flat surfaces,” notes Oxford Bibliographies, in order to create “complex spatial patterns.” Scholar Robert D. Stevick describes these properties on the ornate dyed leather covers of the St. Cuthbert Gospel:

There is interlace pattern in two panels on the front cover, step-pattern implying two crosses on the lower cover, a prominent double vine scroll at the center of the front cover—elements of this early art that have been well catalogued for their individual features as well as for their affinities to similar decorative elements in other artifacts.

Bound with a sewing technique that originated in North Africa (and therefore often called “Coptic sewing”), the “simple but elegant” book, Meier explains, “reflects the transmission of publishing knowledge across Europe” from the Mediterranean. Its small size and placement in a leather pouch is also significant. St. John’s Gospel “was sometimes employed as a protective talisman,” worn in a pouch on the body to ward off evil. Why one of Cuthbert’s admirers would have given such a talisman to his corpse remains unclear.

If you can’t make it to the British Library to see this fascinating artifact in person, you can see its miraculously well-preserved binding and pages in scans at the British Library site here.

via JSTOR Daily

Related Content:

1,000-Year-Old Manuscript of Beowulf Digitized and Now Online

Wearable Books: In Medieval Times, They Took Old Manuscripts & Turned Them into Clothes

Josh Jones is a writer and musician based in Durham, NC. Follow him at @jdmagness

Nice to know that the treasured items we’ll be buried with will potentially be taken from our eternal rest, and put on display by soulless scientists for curiosity’s sake. The saint may be dead, but it’s still his possession…his property!

If you’d bothered to read the article, the book was added to his crypt some 50–100 years after his death. I’m sure the saint won’t miss what he didn’t know he had.

So, you didn’t read the article.

You people are missing the point. Even if it had been added right at his earth he “wouldn’t miss what he didn’t know he had”. It’s about the fact that it was added to his remains makes it part of his belongings. All you people are doing is rationalizing how soulless, inhumane, callous “scientists” are rummaging through the remains of someone on the more equally so than not justification that other grave robbers use all throughout history. Just as with other grave robbers, once all the graves have been looted and all historical things catalogued, there will no longer be any history created and it will therefore come to an end. There will be no manuscript to be found of a psychologically and narcissistic rationalizing callous society of “scientists” that digitized everything that will immediately be erased from one EMP. No tombs or reliquaries are created or added to remains that will be found in the future, because today’s society does not believe anything not hedonic and immediate in nature. We have reached a state where not just history and culture have been arrested and suffocated, but even biology and natural selection are being suffocated and perverted. It is the real extinction event nonone even has the capacity to comprehend, let alone the license to discuss as savagery masquerading as “diversity” and “tolerance” falls over the civilized and cultures world like the pestilence it is. The end is not near, the end of humanity is near, giving way to inhumanity.

“There is no life without change. The real tragedy is that we are always fearful of change and resist it vehemently.”

― Debasish Mridha

Don’t know why some are up in arms about removing this bible, and would prefer it to rot. it’s unique , from a time when very little written material exists. Should we it be left with the bones — NO! He is dead, and long gone he won’t know the difference. Certainly the cleric’s from the 11 century had no qualms about removing it.

I would imagine the monk would be pleased that after 1,300 years a bible given to him posthumously would be seen by hundreds of people.

Best answer yet. I believe the point of the bible was to spread the message, not to own it. I too believe he would be happy if people were to not only see it, but to read it.