All of the musicians I’ve played with have been improvisers, whether they came from jazz, rock, folk, or whatever. As a loose improvisor myself, I’ve found it difficult to collaborate with trained classical players. It’s not for lack of trying, but—while we like to think of music as a universal language—the means of communication were strained at best. Classical musicians have a hard time with spontaneous composition; jazz players are generally comfortable with loose technique and can adapt to experiments and unexpected shifts.

I’d always chalked this difference up to different kinds of training (or lack thereof in my case), but a new study by researchers in Leipzig suggests a deeper neurological basis, at least when it comes strictly to jazz versus classical musicians. Researchers at the Max Planck Institute for Human Cognitive and Brain Sciences studied the brains of thirty pianists—half jazz players, half classical. They found, the Institute reports, that “different processes occur in jazz and classical pianists’ brains, even when performing the same piece.”

It’s a conclusion players themselves intuitively understand. As jazz pianist Keith Jarrett once said, when asked if he would ever play both jazz and classical in concert, “No… it’s [because of] the circuitry. Your system demands different circuitry for either of those two things.” This isn’t due to hard-wired biological differences, but to the way the brain creates pathways over time in response to different musical activities. As neuroscientist Daniela Sammler puts it:

The reason could be due to the different demands these two styles pose on the musicians—be it to skillfully interpret a classical piece or to creatively improvise jazz. Thereby, different procedures may have established in their brains while playing the piano which makes switching between the styles more difficult.

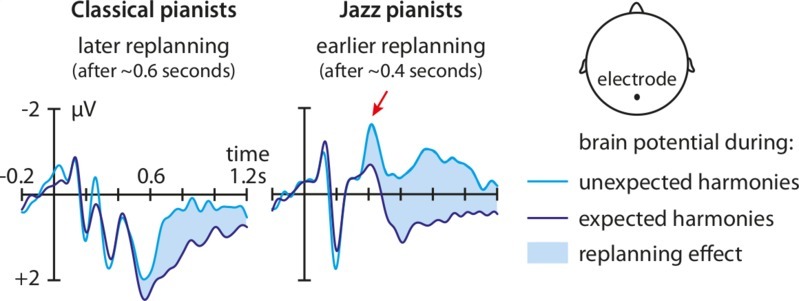

On its face, the study may hardly seem illuminating. We have long known that repeated actions change the structure of the brain, so why should it be different for musicians? Things get a little more interesting as we dig into the details. One finding, study author Robert Bianco notes, shows that jazz pianists “replan… actions faster than classical pianists” and were “better able to react and continue their performance” when asked to play a harmonically unexpected chord within a standard progression (see graph below).

On the other hand, Science Daily reports, classical pianists’ brains showed, “a stronger awareness of fingering, and consequently they made fewer errors while imitating the chord sequence.” The critical distinction between the two relates to how they plan movements, with classical pianists focusing on the “How” of technique and jazz players on the “What” of adaptation to the unexpected.

Other studies substantiate the findings. Researchers at Wesleyan University focused on the role of what they call “expectancy” in three groups: jazz improvisers, “non-improvising musicians,” and non-musicians. Jazz players trained to improvise not only preferred unexpected chords in a progression, but their brains reacted and recovered more quickly to the unexpected, suggesting a higher degree of creative potential than both classically trained musicians and non-musicians.

“The improvisatory and experimental nature of jazz training,” the study’s authors write, “can encourage musicians to take notes and chords that are out of place, and use them as a pivot to transition to new tonal and musical ideas.” However, the comparison between the two groups does not place value on one over the other.

While jazz improvisation may better teach creativity, classical training, as neuroscientist Ardon Shorr argues in his TEDx talk above, may better train the brain in information processing. These studies show that the effect of music on the brain cannot be studied without regard for the differing neurological demands of different kinds of music, just as the study of language processing cannot be limited to just one language.

Such studies can also give us an even greater appreciation for the rare musician who can easily switch between jazz and classical in the same performance, like the late, great Nina Simone. See her work a Bach-influenced fugue into “Love Me or Leave Me,” at the top.

Related Content:

New Research Shows How Music Lessons During Childhood Benefit the Brain for a Lifetime

The Neuroscience of Bass: New Study Explains Why Bass Instruments Are Fundamental to Music

Josh Jones is a writer and musician based in Durham, NC. Follow him at @jdmagness

Never been crazy about the word “Jazz” but those who play improvised or pop music generally feel the need to be responsible for knowing the ins and outs of the entire chord/harmonic sequence of a piece.

Classical students after years of lessons more concerned about fingerings, dynamics, phrasing etc.

To use the analogy of house construction they are more concerned with the interior decoration, the shade of the outside paint color and the landscaping without having even a rudimentary interest in the actual framing and wiring of the structure.

Until I played “jazz” for ten years I never appreciated how advanced the harmonies of Chopin were.

There’s a lot more there than pretty melodies that can be mastered by decent technicians with facile finger memory.

Josh says music is the universal language, and indeed, it is. It is also an amazing conduit for human expression. I’ve been a musician for over 50 years (I’m 61), of the variety found in the “not classically trained” camp. That is I am trained, just not in the Classical.

Here’s my take on why us improvisarios do not relate to our Classical adepts across the divide…while music is the best form of human expression, we players go through life expressing ourselves through our music, while the higly trained classical musicians spend their lives expressing another human’s musical vision.

Improvisation played an important role in the early years of piano performance in Western Europe. Beethoven in particular was lionized by his contemporaries for his extraordinary improvisations. We get a taste of this in his Diabelli Variations, and can only imagine the range and imagination of his improv, which tapered off with growing deafness in his 30s.

Taking this in the abstract– I could see this going opposite.

Classical musicians have to remember MORE music when performing– whole sonatas etc.

(Although jazzers have stores of riffs, chord tensions, line cliches etc– but portions of these are generic for any chart, or embedded physically rather than mentally). I could argue jazz is mostly embedded physically– the knowing is more implicit and habit based– ie less mental representation. I realize that sounds dumb because we think of classical players as being very rote.

And jazz is inextricably style obsessed. Swing is a lot harder to convey than classical aura.

SO thinking flexibly I could see classical peeps as being more concerned with the WHAT and jazzers with the how.

(I get that classical music is particular aesthetically.. and I get that jazz relies more on content/note combination to make its conveyance– but for the sake of flexible thought I brainstormed the above. Could keep the paradigm loose).

Only this post proved that any body is not equal you and your level

Thank you for all your help. Your service was excellent and very FAST. Many thanks for you kind and efficient service. I have already and will definitely continue to recommend your services to others in the future.