In the introduction to her book Broad Strokes, writer and art history scholar Bridget Quinn describes her discovery of Lee Krasner, accomplished abstract expressionist painter who just happened to have been married to Jackson Pollock. That biographical detail warranted Krasner a footnote, but little more, in the art books Quinn studied in college. Learning of Krasner sent Quinn on a quest to find other women left behind by art history. “My fixation with these artists went beyond feminism,” she writes, “if it had anything to do with it at all. I identified with these painters and sculptors the way my friends identified with Joy Division or The Clash or Hüsker Dü.”

Much has changed since 1987, when Quinn’s fandom began, but Krasner is still one of the few female artists to have ever had a retrospective show at New York’s Museum of Modern Art. And one artist every student of art history should know, Baroness Elsa von Freytag-Loringhoven, remains almost completely obscure. What’s so important about von Freytag-Loringhoven? She was a pioneering Dada artist and poet—well-known in the 1910s and 20s. “Her work was championed by Ernest Hemingway and Ezra Pound,” writes John Higgs at the Independent (she appears in Pound’s Canto XCV). She “is now recognized as the first American Dada artist, but it might be equally true to say she was the first New York punk, 60 years too early.”

Von Freytag-Loringhoven also deserves the credit, it seems, for one of the most groundbreaking art objects to ever appear in a gallery: Fountain, the urinal signed “R. Mutt” that Marcel Duchamp claimed as his own and which has made him a legend in the history of art. The story, I imagine, might seem depressingly familiar to every woman who has ever had a male boss publish her work with his name on it. Even more frustratingly, the “glaring truth has been known for some time in the art world,” according to the blog of art magazine See All This. Yet, “each time it has to be acknowledged, it is met with indifference and silence.”

The truth first emerged in a letter from Duchamp to his sister—discovered in 1982 and dated April 11th, 1917, a few days before the exhibit in which Fountain first appeared—in which he “wrote that a female friend using a male alias had sent it in for the New York exhibition.” The name, “Richard Mutt,” was a pseudonym chosen by Freytag-Loringhoven, who was living in Philadelphia at the time and whom Duchamp knew well, once pronouncing that “she is not a Futurist. She is the future.” (See her Portrait of Marcel Duchamp, above, in a 1920 photograph by Charles Sheeler.)

Why did she never claim Fountain as her own? “She never had the chance,” notes See All This. The urinal was rejected by the exhibition organizers (Duchamp resigned from their board in protest), and it was probably, subsequently thrown away; nothing remained but a photograph by Alfred Stieglitz. Von Freytag-Loringhoven died ten years later in 1927.

It was only in 1935 that surrealist André Breton brought attention back to Fountain, attributing it to Duchamp, who accepted authorship and began to commission replicas. The 1917 piece “was destined to become one of the most iconic works of modern art. In 2004, some five hundred artists and art experts heralded Fountain as the most influential piece of modern art, even leaving Picasso’s Les Demoiselles d’Avignon behind.”

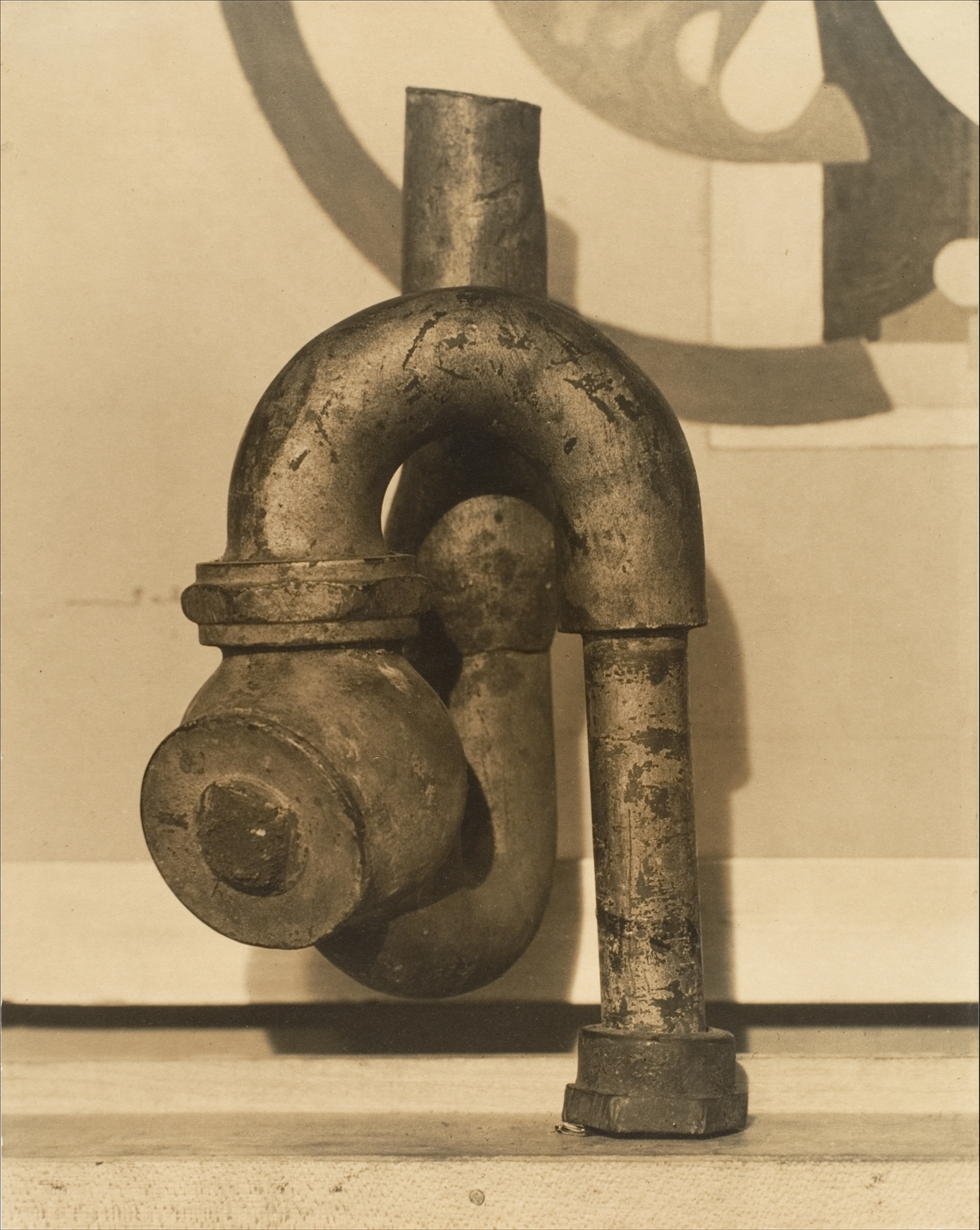

Duchamp’s letter is not the only reason historians have for thinking of Fountain as von Freytag-Loringhoven’s work. “Baroness Elsa had been finding objects in the street and declaring them to be works of art since before Duchamp hit upon the idea of ‘readymades,’” writes Higgs. One such work, a “cast-iron plumber’s trap attached to a wooden box, which she called God” (above), was also misattributed, “assumed to be the work of an artist called Morton Livingston Schaumberg, although it is now accepted that his role in the sculpture was limited to fixing the plumber’s trap to its wooden base.”

“Fountain is base, crude, confrontational and funny,” writes Higgs, “Those are not typical aspects of Duchamp’s work, but they summarize the Baroness and her art perfectly.” Duchamp later claimed to have bought the urinal himself, but later research has shown this to be unlikely. Higgs’ book Stranger Than We Can Imagine explores the issues in more depth, as does an article in Dutch published in the See All This summer issue. What would it mean for the art establishment to acknowledge von Freytag-Loringhoven’s authorship? “To attribute Fountain to a woman and not a man,” the magazine writes, “has obvious, far-reaching consequences: the history of modern art has to be rewritten. Modern art did not start with a patriarch, but with a matriarch.”

Learn more about Elsa von Freytag-Loringhoven at The Art Story.

via See All This

Related Content:

Hear Marcel Duchamp Read “The Creative Act,” A Short Lecture on What Makes Great Art, Great

Josh Jones is a writer and musician based in Durham, NC. Follow him at @jdmagness

Thank you for revealing this to me. It’s a bit of a shock. (To me also about Schamberg.) I’m sort of depressed about how this pattern just repeats itself (and how long it takes to find out).

It’s great article but please correct “Jackson Pollack” to “Jackson Pollock”. Given the times we live, credibility and good journalism is based on keeping an eye on this kind of details. Thank you for your hard work and for your devotion to your medium.

She seems amazing in her own right, but the dates don’t add up. She didn’t meet Duchamp until after the war broke out and her husband left to join the war, yet Duchamp was creating readymades like “Bicycle Wheel” as early as 1913.

So who came up with the concept of “Ready-mades”? It wasn’t the creator of the fountain. Duchamp was creating these 4 years prior. But let’s look at the letters.

The first is the seemingly damning letter selectively quoted in the article:

“One of my female friends under a masculine

pseudonym, Richard Mutt, sent in a porcelain urinal as a sculpture”

But this is the last in several letters. Let’s look at the full context.

Two more things come to light from the collection of letters.

1) Duchamp outlines his concept of ready-mades a full year and a half before the fountain was submitted to The Independents in the following letter to his sister, Suzanne:

“Now, if you went up to my place you saw in my studio a bicycle wheel and a bottle rack. I had purchased this as a sculpture already made. And I have an idea concerning this said bottle rack: Listen.

Here, in N.Y., I bought some objects in the same vein and I treat them as “readymade.” You know English well enough to understand the sense of “ready made” that I give these objects. I sign them and give them an English inscription.”

2) He later moves on to outlining his concept of “art at a distance”, instructing Suzanne how to create a ready-made under his name in the following letter. Not just the inventor of post modernism, but a precursor to Warhol.

“You take for yourself this bottle rack. I will make it a “Readymade” from a distance. You will have to write at the base and on the inside of the bottom ring in small letters painted with an oil-painting brush, in silver white color, the inscription that I

will give you after this, and you will sign it in the same hand as follows:

[after] Marcel Duchamp”

So it’s clear to anyone following that Duchamp was instructing people to take objects, sign/inscribe them, and have this be his art. Not content with just finding the art, he then wanted the art to be found on his behalf, as his later work demonstrates. It’s kinda brilliant.

OK, so if someone other than Duchamp created the fountain in 1917 on his behalf, who was it?

The article draws a hasty conclusion that it must have been Elsa von Freytag-Loringhoven, but, if you look at the following letter, it seems to indicate he was requesting from many people:

“Did you write the phrase on the readymade? — do so and send it (the phrase) to me indicating how you did it. I am writing a little to everyone at the moment.”

OK, so his sister Suzanne created one readymade under Duchamps instruction, this much is clear. (Namely “Bottle Rack”)

The candidates for “The fountain” are now narrowed down to Elsa von Freytag-Loringhoven, and his friend and painter Louise Norton.

Unfortunately for Elsa, Stieglitz’s original photograph of “The Fountain” actually shows the entry slip in the bottom left corner.

As seen here: https://i.imgur.com/X8VmHACr.jpg

You can see the name R. Mutt, and the address of the entrant.

Richard Mutt

110 West 88th St

New York City

Which just so happens to be the address Louise Norton was living at in 1917.

So, The Fountain was created by Lousie Norton at the request of Duchamp as part of his ongoing “readymade” concept.

Duchamp not only forged post-modernism, but assembly line art later credited to Warhol.

As always, the truth is much more interesting…

Does it really matter who made or claimed this as a significant work of art? The claim that it is so groundbreaking as a work of art still has to be made — ultimately no one has the authority to say what it is. It’s more of a French scatological burlesque joke, and even by Duchamp’s time this kind of thing was already ancient history.

If the attribution to Duchamp is dismissed, and instead ‘The Fountain’ is attributed to Elsa von Freytag-Loringhoven, how does that change the meaning of the work? It is mentioned here that Breton brought attention back to the Fountain in 1935, and that Duchamp accepted authorship and began with replicas. If this is so, might this not have contributed significantly to its status as an important artwork to begin with? Regardless of post-modernism or Warhol or anything or anyone else, the fact that it passed into the stage of generating ‘multiples’, something which in one way or another Duchamp (and others) had already been working with, it would have started to beg more questions and elaborate more problems of interpretation — thus providing a reason for its significance. You folks are treating this like it’s a drawing by a Renaissance artist who everyone thought was by one artist, but turns out it is by another. The ‘Fountain’ doesn’t function that way. So to repeat the question: if the work turns out to be by Freytag-Loringhoven, how does that change the meaning of the work? Have a reason for writing this article. Would it cause historical revisionism? It’s very nice and charming the 500 people think it is so important, but all that proves is that 500 people can all agree on something. It’s a lot easier to achieve that in the world of art and academia today than it would have been 30 or 40 years ago.

“‘My fixation with these artists went beyond feminism,’ she writes, ‘if it had anything to do with it at all.’ ” There’s really no reason to make this unfeminist, is there

So what is it about the ‘Fountain’ that makes it feminist? For the last 40 years, and counting, we’ve had feminist essentialism, particularly Mary Daly who I think is one of the great thinkers of the late modern period although so many feminists would disagree. Even the idea that the ‘Fountain’ is significant solely for having been conceived and made by a woman doesn’t really add up given the vagaries of its influence. That is, even by the terms of the article.

The idea that Baroness Elsa was the real author of Marcel Duchamp’s Fountain was first proposed by Glyn Thompson in 2008, and has now attained the status of a full-blown conspiracy theory. It was an absolutely preposterous claim when it was introduced, and it was quickly embraced by anyone who thinks a female artist was wronged and the authorship of this game-changing artifact was stolen from her. Every shred of evidence presented to support this theory is purely circumstantial, but what few people realize is that it was presented with an agenda: to discredit Duchamp and thereby all of contemporary art that followed from his example. The main reason it won’t go away is because of the MeToo Movement and a twisted feminist agenda. Of course, it is a laudatory impulse to resuscitate interest in the work of a forgotten female artist, but using Baroness Elsa for this purpose is unquestionably misguided and serves no legitimate feminist agenda. She is an artist worthy of attention in her own right, and not as someone who had her ideas stolen by a more powerful male artist, because that simply did not happen in this case.

Well at least the ‘Fountain’ can still cause a stir in North America it seems, even if the rest of the world has moved on. No one here is talking about the actual object and the potentially interesting result of attributing it to someone other than Duchamp. You guys just seem to be bureaucratically vain, trying to score adolescent debating points, and uninterested in the effect of art on society — specifically this work.

These assertions have been kicking around for a long time and fail the sniff test. Duschamp’s work was broader than just the urinal piece.

See ‘An Audience of Artists’ and a recent Art Forum discussion of Duschamp for a richer and more accurate viewpoint.

None of which, btw, diminishes Elsa’s work.

These kinds of wishful rewrites of history should not be advanced by Art History departments at major Universities dedicated to, well… History.

Sure there is. A great number of people [unfortunately and without good reason] write things off that have ties to feminism. If the goal here is exposure and widespread acceptance, it behooves the author to disconnect from any thought styles considered by others as ‘radical’. Whether feminism is actually ‘radical’ is beside the point.

The question may go a little further. I’ve been under the impression that the first to ask a question about Fountain’s authorship was Irene Gammel, though I need to go back to check. However my point is that dada in both it’s New York and Zurich incarnations was highly collaborative. Elsa notably worked with both Duchamp and Man Ray, her work and her body appeared in the only edition of New York Dada 1921. She was a remarkable artist and deserves far more recognition, her art has been dismissed as feminine dada when it was truly feminist dada. However the collaborative ethos of much of dada surely makes the attribution of a single artifact to one artist rather than another rather unimportant.

There is rightly a great admiration for Duchamp, his was a unique mind but I believe that without the contributions of the group of other minds around him, his impact on posterity would have been far less. Fortunately he was open to other ideas, they all were.

Readers wishing to judge the impartiality of Mr Naumann’s unsubstantiated opinion that the de-attribution of Mutt’s gesture from the oeuvre of Marcel Duchamp, and its re-attribution to that of Elsa von Freytag Loringhoven, constitutes a “conspiracy theory,” might find it helpful to consult the following:

[1]‘Sloppy Virtuosity at the Temple of Purity No. 23: Francis Naumann’s Reccurrent Haunting Ghosts.’ Academia.edu.

[2] ‘Only in Philadelphia.’ Moore Women Artists. Philadelphia.

[3] ”God” by Baroness Elsa von Freytag-Loringhoven and Morton. L. Schamberg. Archive.org / Reviews.

[4] ‘Elsa in Philadelphia.’ Summerhall, Edinburgh. 2017.

[5] ‘Duchamp’s Urinal? The Facts Behind the Façade.’ Wild Pansy Press, 2015.

As for “circumstantial” evidence, Mr Naumann fails to mention that the misattribution of Mutt’s urinal to Duchamp was made not in 1917 but in 1935, by Andre Breton, who cited no evidence whatsoever in support of his airy fancy. This is hardly surprising, since, as Mr Naumann also to fails to note, there is none.

Does anyone here actually give a toss about the work itself? What a feminist reading of it might bring to light?

The proposition that Elsa von Freytag-Loringhoven and not Duchamp created Fountain is an interesting one. The well considered response by Lachlan Phillips in the comments section carries weight as well. The one thing I cannot understand is the contention from John Higgs that “Fountain is base, crude, confrontational and funny… Those are not typical aspects of Duchamp’s work.” Wrong, those are precisely aspects of Duchamp’s work.

See also:

Marcel Duchamp. The Enigma of the Urinal. L’énigme de l’urinoir. Hamburg: Tredition, 2017.

Marcel Duchamp is now also officially a fraud. Not that I ever felt any other way about his “art” especially the “fountain”. While everyone was hyping him for that piece of shithouse I always thought: “Oh wow. How daring. You really showed them, Marcel. A toilet. Signed. Wooooo.” It has become clear that Duchamp claimed the work of Dada Artist Elsa von Freytag-Loringhoven. Another nice example on how men in power exploit women. But also an empowering message for all female artists today: women can do shit (ty) art too. I hope the Duchamp frenetic crowd of art historians learned their lesson — fricking vicarious agents of the art market.

That’s my statement under a picture of your article: https://www.instagram.com/p/BpCUT0XH-d5/?utm_source=ig_web_copy_link

Dear Lachlan Phillips, thank you for your comment. What you said here was extremely helpful to me.

FYI: you link to the Art Story page for this artist, but Art Story still attributes Fountain to Duchamp.

It seems entirely plausible that Ms. Freytag was the creator behind the idea of “fountain”. That’s the problem with modernist art; it’s even easier to steal a work of art (an idea) than it is to break into a studio and steal an oil painting that resulted from a painters skill. It also seems inevitable that ideas would be in play so that Duchamp and others (Joseph Cornell, for example), would pursue as ready made sculptures.

For an updated summary of the actual facts, see https://atlaspress.co.uk/marcel-duchamp-was-not-a-thief/

hahaha, modern art was such a scam anyways, classist delusions, nothing more. It is important that a woman take credit for the mess thought, right on!!!

Well I think Lachlan Phillips comment really puts an end to the discussion. Even if it wasn’t by Duchamp, which it is, it would be by Louise Norton before Elsa Freytag. Just because some hypothesis has elements enough to say it could be true, doesn’t mean it really is true, specially if the actual story is much more plausible.

And for those diminishing Duchamp’s work or the importance of dada and following movements… maybe you have to study a little more and open your mind for new concepts, or maybe you have to work on your feelings, because this urging hate that drives you to an article just to rant at it, that’s love, not hate. You really like it, but you’re not allowing yourself for some reason. So you compensate expressing hate. Otherwise, you wouldn’t even bother.

What amuses me about the Urinal, given its configuration, is that if we’re used for it’s designed purpose a chap would get their output back in full measure. It really is a “piss take.”

The information given by Glyn Thompson above regarding when and by whom “Fountain” was attributed to Duchamp is verifiably incorrect. See “Duchamp’s ‘Fountain’: the Baroness Theory Debunked” (The Burlington Magazine, 2019), https://www.academia.edu/41828316/Duchamp_s_Fountain_the_Baroness_Theory_Debunked

The question of authorship assumes that the submission of “Fountain” (i.e. with the intention of having it exhibited by the SIA), was a revolutionary art statement. But was it, considering the many incoherencies involved in the events? For example, if Duchamp had outed himself as the author, then the piece would have had a good chance of being accepted, considering his status and functions within the SIA. It was rejected by a small majority. As we know (from Camfield), Katherine Dreier. one of the directors of the SIA (like Duchamp), was very conciliatory and offered him (and R. Mutt) the opportunity to explain the idea behind “Fountain.” Duchamp remained silent… in The Blind Man and for many years thereafter.

An alternative explanation would involve tensions within the SIA as the motivation for a hoax to put rear-guard members on the spot and provide MD and Arensberg an excuse to resign (not a retaliation for Gleizes’ role in 1912, as Th. de Duve argues). As such, it would have been a “team effort” by the avant-garde faction, which would make the issue of authorship moot. It is Posterity that turned “Fountain” into an art statement.

NB: A detail on the submission label in Stieglitz’s photo is worth mentioning: the address was written in the German style (with hyphens) and by someone unfamiliar with the US American style of addressing (thus not Louise Norton?).

I would, but 15 Euros for a 50-page booklet that is half in French is not my idea of fair deal for scholars.

Thank you for taking the time to put all this down.

What I am missing in this discussion is the critical question: was “Fountain” intended in good faith as the revolutionary art statement that it has become?

Considering all the incoherencies (like MD’s letter to Suzanne) and other factors involved in this caper, I don’t think so, and therefore authorship is not the real issue, but the motivation for submitting it and why MD didn’t claim authorship at the time. (More on this in my comment farther down below).