Even by the extreme standards of dystopian fiction, the premise of Ray Bradbury’s Fahrenheit 451 can seem a little absurd. Firemen whose job is to set fires? A society that bans all books? Written less than a decade after the fall of the Third Reich, which announced its evil intentions with book burnings, the novel explicitly evokes the kind of totalitarianism that seeks to destroy culture—and whole peoples—with fire. But not even the Nazis banned all books. Not a few academics and writers survived or thrived in Nazi Germany by hewing to the ideological orthodoxy (or at least not challenging it), which, for all its terrifying irrationalism, kept up some semblance of an intellectual veneer.

The novel also recalls the Soviet variety of state repression. But the Party apparatus also allowed a publishing industry to operate, under its strict constraints. Nonetheless, Soviet censorship is legendary, as is the survival of banned literature through self-publishing and memorization, vividly represented by the famous line in Mikhail Bulgokov’s The Master and Margarita, “Manuscripts don’t burn.”

Bulgakov, writes Nathaniel Rich at Guernica, is saying that “great literature… is fireproof. It survives its critics, its censors, and even the passage of time.” Bulgakov wrote from painful experience. When his diary was discovered by the NKVD in 1929, then returned to him, he “promptly burned it.” Sometime afterward, during the long composition of his posthumously published novel, he burned the manuscript, then later reconstructed it from memory.

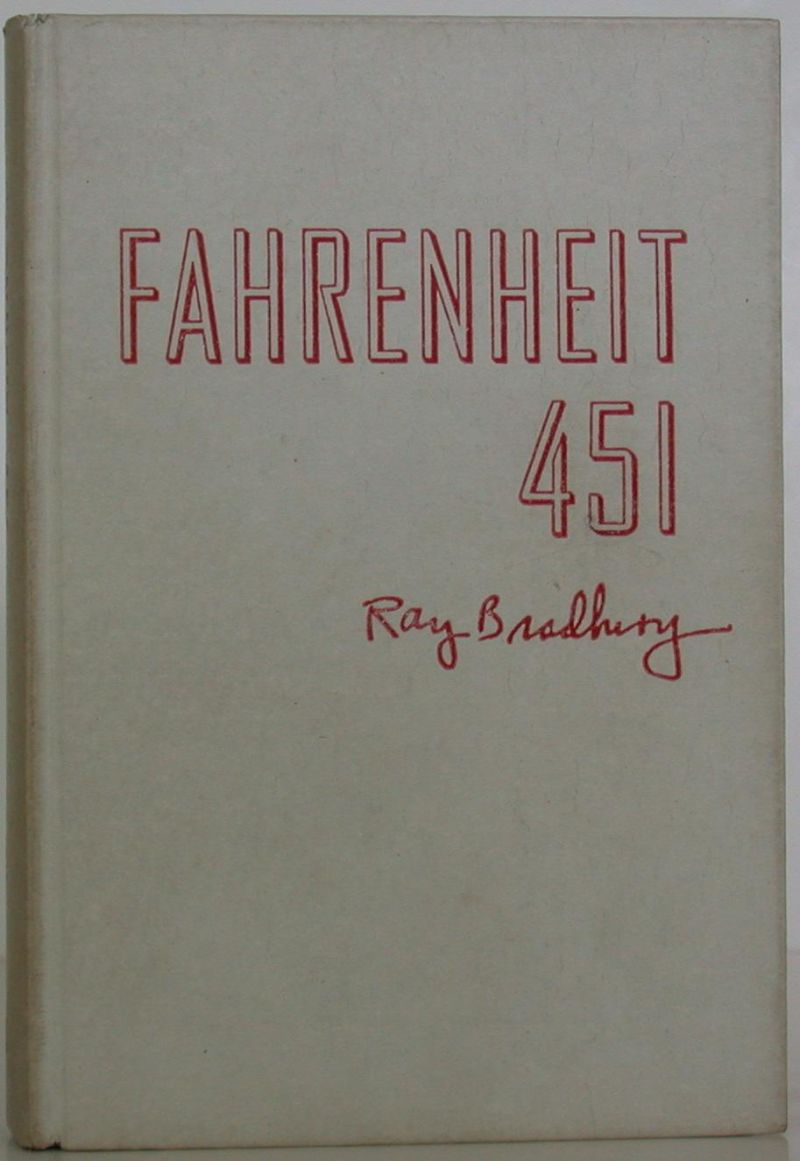

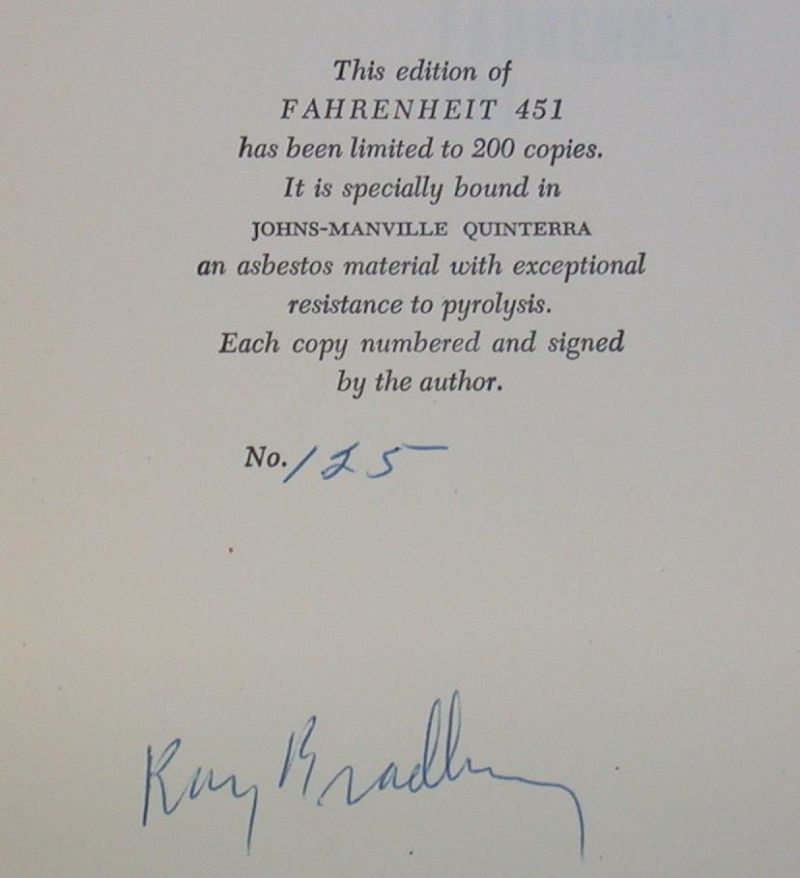

These examples bring to mind the exiled intellectuals in Bradbury’s novel, who have memorized whole books in order to one day reconstruct literary culture. Europe’s totalitarian regimes provide essential background for the novel’s plot and imagery, but its key context, Bradbury himself noted in a 1956 radio interview, was the anti-Communist paranoia of the U.S. in the early 1950s. “Too many people were afraid of their shadows,” he said, “there was a threat of book burning. Many of the books were being taken off the shelves at that time.” Reading the novel as a chilling vision of a future when all books are banned and burned makes the artifact pictured above particularly poignant—an edition of Fahrenheit 451 bound in fireproof asbestos.

Released in 1953 by Ballantine in a limited run of two-hundred signed copies, the books were “bound in Johns-Manville Qinterra,” notes Lauren Davis at io9, “a chrysolite asbestos material.” Now the fireproof covers, with their “exceptional resistance to pyrolysis,” are “much sought after by collectors” and go for upwards of $20,000. A fireproof Fahrenheit 451, on the one hand, can seem a little gimmicky (its pages still burn, after all). But it’s also the perfect manifestation of a literal interpretation of the novel as a story about banning and book burning. All of us who have read the novel have likely read it this way, as a vision of a repressive totalitarian nightmare. As such, it feels like a product of mid-twentieth century fears.

Rather than fearing mass book burnings, we seem, in the 21st century, on the verge of being washed away in a sea of information (and dis- and mis-information). We are inundated with writing—in print and online—such that some of us despair of ever finding time to read the accumulating piles of books and articles that daily surround us, physically and virtually. But although books are still published in the millions, with sales rising, falling, then rising again, the number of people who actually read seems in danger of rapidly diminishing. And this, Bradbury also said, was his real fear. “You don’t have to burn books to destroy a culture,” he claimed, “just get people to stop reading them.”

We’ve misread Fahrenheit 451, Bradbury told us in his later years. It is an allegory, a symbolic representation of a grossly dumbed-down society, hugely oppressive and destructive in its own way. The firemen are not literal government agents but symbolic of the forces of mass distraction, which disseminate “factoids,” lies, and half-truths as substitutes for knowledge. The novel, he said, is actually about people “being turned into morons by TV.” Add to this the proliferating amusements of the online world, video games, etc. and we can see Bradbury’s Fahrenheit 451 not as a dated representation of 40s fascism or 50s repression, but as a too-relevant warning to a distractible society that devalues and destroys education and factual knowledge even as we have more access than ever to literature of every kind.

Related Content:

Josh Jones is a writer and musician based in Durham, NC. Follow him at @jdmagness

The idea of a society that bans books is meant to be provocative. It is far from absurd in a work of fiction. It is meant to have the reader become acquainted with the feeling one gets when the material one may read is censored as it is today in the United States and many Western countries where the media are in such synchrony that people know they are getting little more that tripe, just as the Soviets and those in East Berlin knew. The difference is that they could talk about it without being called a nut. There are other means other than burning. In the twentieth century, on more than one occasion a publisher was ordered to PULP an entire print run for the simple reason that the subject was found not to the thinking of some self appointed censor or group of censors. Today more than ever people are in goose stepping formations complying with ‘political correctness’. Now is as good a time as ever to reprint Bradbury’s most popular novel, F451, and as the author above observes, it is most relevant in the 21st century.