Some films achieve the rare feat of being both colorful escapist fantasy and artful means of reconnecting us with our imperiled humanity. Pixar’s wonderful, animated Coco is such a film, “an exploration of values,” writes Jia Tolentino at The New Yorker, “a story of a multigenerational matriarchy, rooted in the past—whereas real life, these days, feels like an atemporal, structureless nightmare ruled by men.” Central to its fictionalized celebration of Mexican culture and history is a historical figure every grown-up viewer knows—that foremother of Mexican modernism, Frida Kahlo, an artist who seems as necessary to remember now as ever.

Not that Frida Kahlo is in danger of being forgotten. She is adored around the world, an icon for millions of people who see themselves in the various intersections of her identity: Mexican, mestiza, queer, disabled, feminist, uncompromisingly radical, etc….

Kahlo’s identities matter, and she made them matter. She would not be erased or let her edges be planed away and sanded down. Like other confessional artists to whom she is often compared, Kahlo turned her tragically painful, joyously vibrant life into enduring art. To crib Audre Lorde’s description of poetry, her work is a “revelatory distillation of experience.”

But the confessional understanding of Kahlo can present a critical problem, namely the emergence of what Stephanie Mencimer calls “the Kahlo Cult.”

…her fans are largely drawn by the story of her life, for which her paintings are often presented as simple illustration…. But, like a game of telephone, the more Kahlo’s story has been told, the more it has been distorted, omitting uncomfortable details that show her to be a far more complex and flawed figure than the movies and cookbooks suggest.

In any case, we may not need more hagiography of Frida. We find her life, flaws and all, in her work. From the ravages of childhood polio and a horrific traffic accident at 18 (depicted in the drawing below but never in a painting), from love affairs, a deep immersion in Mexican folk art, and a commitment to socialism and the Mexican Revolution, Kahlo created an autobiographical oeuvre like no other. That said, Kahlo herself is so undeniably fascinating a character that “no one need appreciate art to justify being a Kahlo fan or even a Kahlo cultist,” as Peter Schjeldahl once wrote. “Why not? The world will have cults, and who better merits one?”

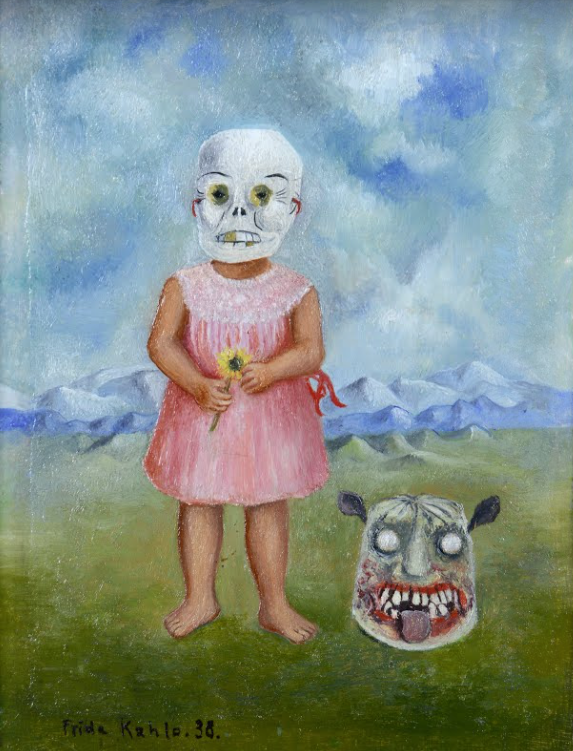

For the art appreciators and Kahlo cultists alike, Google Arts & Culture has created a project that brings together her life and work in ways that illuminate both, with biographical and critical essays, and a thorough exhibit of her work from museums all over the world, including many little-known pieces like her sketches, drawings, and early works; a look at her letters and many photographs of her throughout her life; an online exhibition of her famous wardrobe; several features of her influence on LGBTQ artists, musicians, fashion designers, and much, much more. It’s “the largest Kahlo curation ever assembled,” notes My Modern Met. “The best part? No need to pay a museum fee—it’s available online for anyone to enjoy for free.”

A collaboration “between the tech giant and a worldwide network of experts and 33 partner museums in seven countries,” notes Hyperallergic, Faces of Frida contains 800 artifacts, “including 20 ultra-high resolution images… never digitized till now.” Some of these artifacts are extremely rare, such as “early versions of her work, sketched and etched onto the backs of finished paintings, unseen by anyone without the ability to touch them.” You can also see the places that most influenced her career through five Google Street view tours, “including the famous Blue House in Mexico City in which she was born and died.”

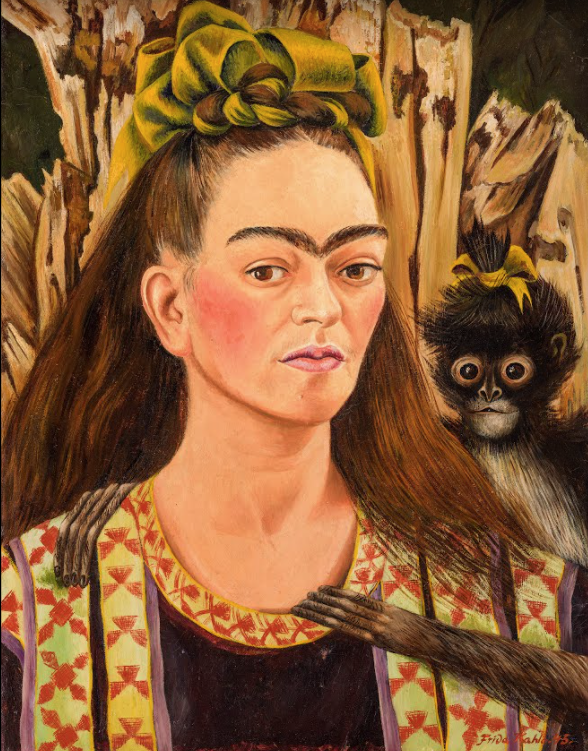

This comprehensive online gallery seeks to encompass every part of Frida’s life, but rarely takes the focus from her work. “Of the 150 or so of her works that have survived,” notes Mencimer, “most are self-portraits. As she later said, ‘I paint myself because I am so often alone, because I am the subject I know best.’” Working outward from herself, she also painted the specific resonances of her time and place, and explored human experiences that transcend personality. “As with all the best artists,” says author Frances Borzello in one of the Google Arts features, “Kahlo’s art is not a diary ingeniously presented in paint but a recreation of personal beliefs, feelings and events through her particular lens into something unique and universal.”

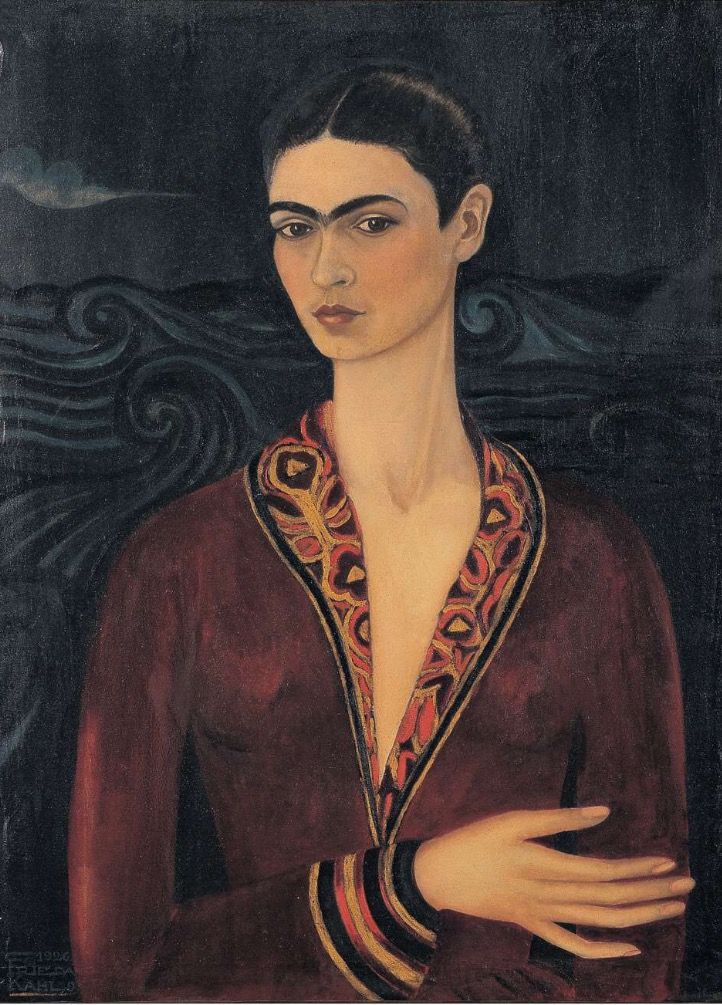

Though a superstar in the land of the dead, during her life Kahlo’s work was greatly overshadowed by that of her famous husband Diego Rivera. She only had two shows in her lifetime, one of them arranged by surrealist Andre Breton, who called her painting “a ribbon around a bomb.” After her death in 1954, she “largely disappeared from the mainstream art world.” There is a certain irony in pointing out that fascination with Kahlo’s work sometimes reduces down to interest in her biography, since it took a 1983 biography by Hayden Herrera to bring her back into the public consciousness. “When it was published” Mercimer writes, “there wasn’t a single monograph of Kahlo’s work to show people what it looked like, but the biography, which could have been the basis for a Univision telenovela, sparked a Frida frenzy.”

How things have changed. No reader of Herrera’s book, or any of the many treatments of Kahlo’s life since then, will come to it sight unseen. Frida’s face—defiant, mustachioed, monobrowed—stares out at us from everywhere. The Google exhibit guides us through a comprehensive contextualization of that haunting, yet familiar gaze. The letters and biographical entries contain insight after insight into the artist’s private and public lives. But ultimately, it’s the paintings that speak. As Borzello puts it, when we really confront Frida’s work, we may be struck by “how helpless words are in the face of the strange richness of those images.” She invented new visual vocabularies of pain, pleasure, pride, and perseverance. Visit Faces of Frida here.

Related Content:

Frida Kahlo’s Colorful Clothes Revealed for the First Time & Photographed by Ishiuchi Miyako

Artists Frida Kahlo & Diego Rivera Visit Leon Trotsky in Mexico: Vintage Footage from 1938

The Frida Kahlo Action Figure

Josh Jones is a writer and musician based in Durham, NC. Follow him at @jdmagness

Leave a Reply