The study of musical instruments opens up vast histories of sound reverberating through the centuries. Should we embark on a journey through halls of Europe’s musical instrument museums, for example, we should soon discover how limited our appreciation for music history has been, how narrowed by the relative handful of instruments allowed into orchestras, ensembles, and bands of all kinds. The typical diet of classical, romantic, modern, jazz, pop, rock, R&B, or whatever, the music most of us in the West grow up hearing and studying, has resulted from a careful sorting process that over time chose certain instruments over others.

Some of those historic instruments—the violin, cello, many wind and brass—remain in wide circulation and produce music that can still sound relevant and contemporary. Others, like the Mellotron (above) or barrel organs (like the 1883 Cylinderpositiv at the top), remain wedded to their historical periods, making sounds that might as well have dates stamped on them.

You could—and many an historian has, no doubt—travel the world and pay a personal visit to the museums housing thousands of musical instruments humans have used—or at least invented—to carry melodies and harmonies and keep time. Such a tour might constitute a life’s work.

But if you’re on a budget or your grant doesn’t come through, you can still tour Europe’s musical instrument museums, and two museums in Africa, from the comfort of your home, office, or library thanks to MIMO, Musical Instrument Museums Online, a “consortium of some of Europe’s most important musical instrument museums” offering “the world’s largest freely accessible database for information on musical instruments held in public collections.”

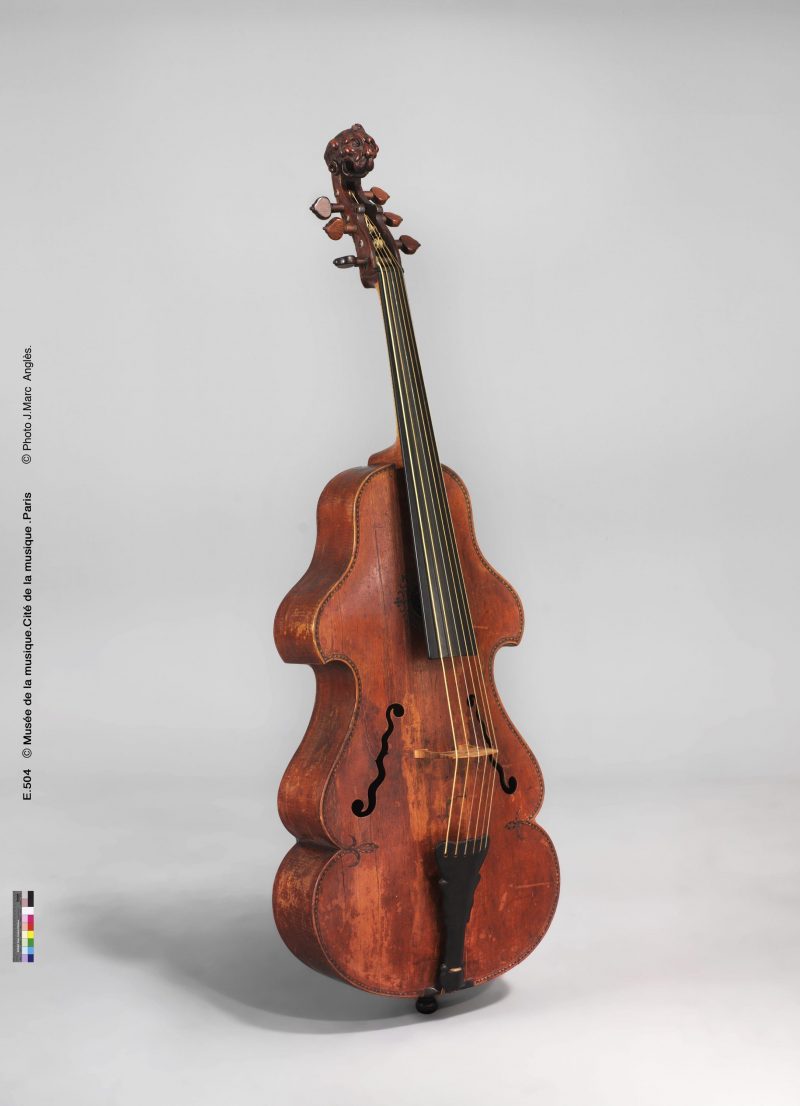

The enormous online collection houses, virtually, tens of thousands of instruments from over two dozen regions around the globe. (There are 64,259 instruments in total.) Find an Italian Basse de Viole (above) from 1547 or an ornate Egyptian darabukka (below). And, of course, plenty of iconic—and rare—electric guitars and basses.

You can search instruments by maker, country, city, or continent, time period, museum, and type. (Wind, Percussion, Stringed, Zithers, Rattles, Bells, Lamellaphones, etc….) Researchers may encounter a few language hurdles—MIMO’s about page mentions “searching in six different languages,” and the site actually lists 11 language categories in tabs at the top. But users may still need to plug pages into Google translate unless they read French or German or some of the other languages in which descriptions have been written. Refreshingly consistent, the photographs of each instrument conform to a standard set by the consortium that provides “detailed guidelines on how to set up a repository to enable the harvesting of digital content.”

But enough about the site functions, what about the sounds? Well, in a physical museum, you wouldn’t expect to take a three-hundred-year-old flute out of its case and hear it played. Just so, most of the instruments here can be seen and not heard, but the site does have over 400 sound files, including the enchanting recording of Symphonion Eroica 38a (above), as played on a mechanical clock from 1900.

As you discover instruments you never knew existed—such as the theramin-like Croix Sonore (Sonorus Cross), created by Russian composer Nicolas Obukhov between 1926 and 1934—you can undertake your own research to find sample recordings online, such as “The Third and Last Testament,” below, Obukhov’s composition for 5 voices, organ, 2 pianos, orchestra, and croix sonore. Obukhov’s experiments with instruments of his own invention prompted his experiments in 12-tone composition, in which, he declared, “I forbid myself any repetition.” Just one example among many thousands demonstrating how instrument design forms the basis of a wildly proliferating variety of musical expressions that can start to seem endless after a while.

via @dark_shark

Related Content:

Watch a Musician Improvise on a 500-Year-Old Music Instrument, The Carillon

Musician Plays the Last Stradivarius Guitar in the World, the “Sabionari” Made in 1679

Josh Jones is a writer and musician based in Durham, NC. Follow him at @jdmagness

Thanks for sharing this. I’m currently working on the f# minor nocturne! they’re beautiful pieces. Afte completion of this, I would go for guitar lessons.

Don’t get me wrong, you have to be strong and confident to be successful in just about anything you do – but with music, there’s a deeper emotional component to your failures and successes. If you fail a chemistry test, it’s because you either didn’t study enough, or just aren’t that good at chemistry (the latter of which is totally understandable). But if you fail at music, it can say something about your character. It could be because you didn’t practice enough – but, more terrifyingly, it could be because you aren’t resilient enough. Mastering chemistry requires diligence and smarts, but mastering a piano piece requires diligence and smarts, plus creativity, plus the immense capacity to both overcome emotional hurdles, and, simultaneously, to use that emotional component to bring the music alive.

Before I started taking piano, I had always imagined the Conservatory students to have it so good – I mean, for their homework, they get to play guitar, or jam on their saxophone, or sing songs! What fun! Compared to sitting in lab for four hours studying the optical properties of minerals, or discussing Lucretian theories of democracy and politics, I would play piano any day.

But after almost three years of piano at Orpheus Academy, I understand just how naïve this is. Playing music for credit is not “easy” or “fun” or “magical” or “lucky.” Mostly, it’s really freakin’ hard. It requires you to pick apart your piece, play every little segment over and over, dissect it, tinker with it, cry over it, feel completely lame about it, then get over yourself and start practicing again. You have to be precise and diligent, creative and robotic. And then – after all of this – you have to re-discover the emotional beauty in the piece, and use it in your performance.

While I agree with your opinion on learning and sticking with music is a challenge, it is also just like anything else. Yes, music has it’s hardships and effects your emotional well-being. However, so does playing / mastering cooking, sports, becoming a doctor, etc. Futhermore, to become GREAT at ANYTHING is “freakin’ hard.”

Anyways, I got reading this, then read your comment and it inspired me. Great article.

I really need an assistance to own musical instrument. Am all passionate to music… Please help me