Economically depleted but filled with the desire to pose questions about the future in radically new ways, postwar Europe would prove fertile ground for the development of avant-garde art. Though that environment produced a fair few stars over the second half of the twentieth century, their work represents only the tip of the iceberg: bringing the rest out of the depths and onto the internet has constituted the last few years’ work for Forgotten Heritage. A collaboration between institutions in Poland, Belgium, Croatia, Estonia, and Germany supported by Creative Europe, the project offers a database of European avant-garde art — including many works still daring, surprising, or just plain bizarre — never properly preserved and made available until now.

Forgotten Heritage’s About page describes the project’s goal as the creation of “an innovative online repository featuring digitised archives of Polish, Croatian, Estonian, Belgian and French artists of the avant-garde movement occurring in the second half of the 20th century,” meant to eventually contain “approximately 8 thousand of sorted and classified archive entries, including descriptive data.”

Currently, writes Hyperallergic’s Claire Voon, its site “offers visitors around 800 records to explore, from documentation of artworks to texts. The majority of works stem from to the ’60s and ’70s, as a timeline illustrates, with the most recent piece dating to 2005. This interactive feature, which has embedded links to individual artists’s biographies and examples of their artworks, is one way to explore the well-designed archive.”

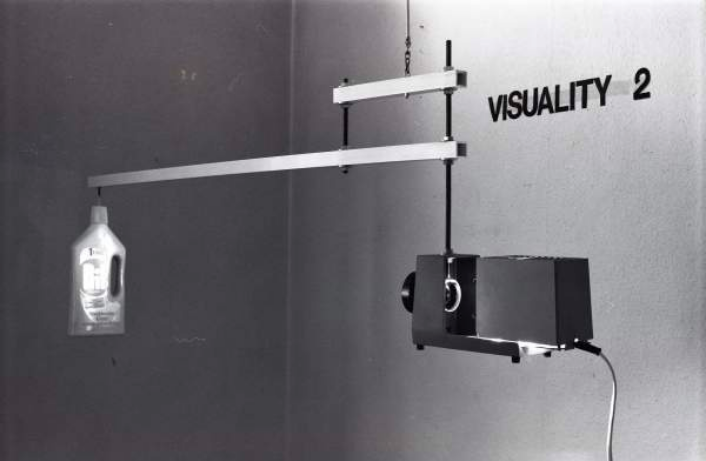

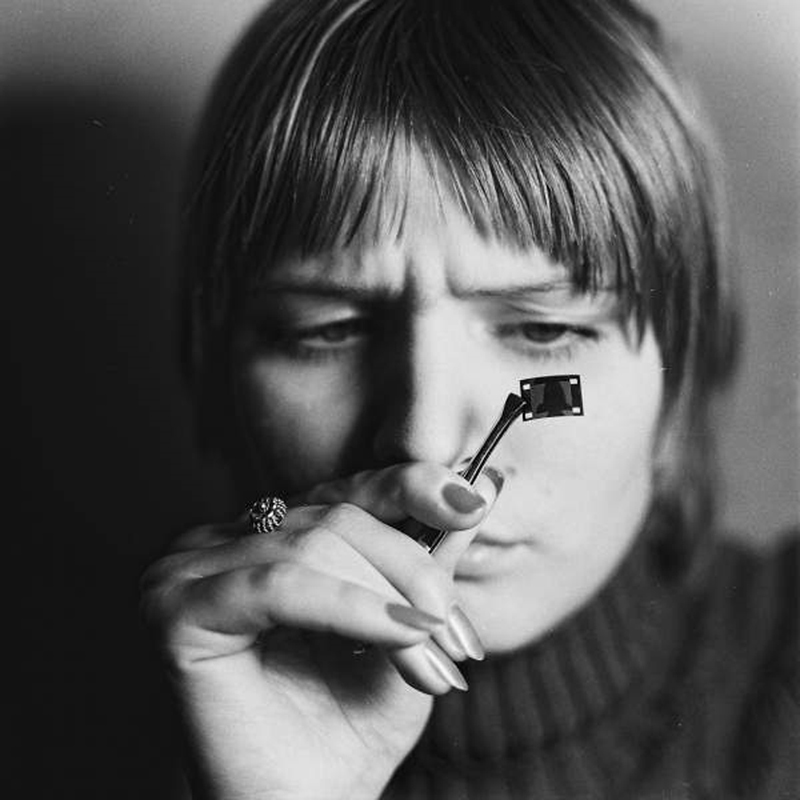

Forgotten Heritage thus makes it easy to discover artists previously difficult for even the avant-garde enthusiast to encounter. Visitors can also browse the growing archive by the medium of the work: painting (like Jüri Arrak’s Artist, 1972, seen at the top of the post), installation (Wojciech Bruszewski’s Visuality, 1980), film (Anna Kutera’s The Shortest Film in the World, 1975), “photo with intervention” (Edita Schubert’s Phony Smile, 1997), Olav Moran’s “Konktal” and many more besides.

Voon cites Marika Kuźmicz’s estimate that about 40 percent of it, mostly from Belgian and Estonian artists, has never before been available online. Debates about whether an avant-garde still exists, in Europe or anywhere else, will surely continue among observers of art, but as a visit to Forgotten Heritage’s digital archives reveals, the avant-garde of decades past, when rediscovered, retains no small amount of artistic vitality today.

via Hyperallergic

Related Content:

Based in Seoul, Colin Marshall writes and broadcasts on cities and culture. His projects include the book The Stateless City: a Walk through 21st-Century Los Angeles and the video series The City in Cinema. Follow him on Twitter at @colinmarshall or on Facebook.

Leave a Reply