Yesterday we wrote of the low opinions the eminent J.R.R. Tolkien and his friend C.S. Lewis held for the “vulgar” creations of Walt Disney. As a counterpoint to their disdain for popular entertainment, we might turn—as writer Steven Graydanus does in Disney’s defense—to their contemporary, the Catholic apologist and prolific essayist, journalist, poet, and writer of detective novels and short stories, G.K. Chesterton.

But we aren’t talking Disney here, but hard-boiled pulp fiction, a genre I think Chesterton would have liked. Chesterton’s work “was entirely popular in nature,” notes Graydanus. He was “a great defender of popular and even ‘vulgar’ culture.” Take his essay “A Defense of Penny Dreadfuls,” which begins:

One of the strangest examples of the degree to which ordinary life is undervalued is the example of popular literature, the vast mass of which we contentedly describe as vulgar. The boy’s novelette may be ignorant in a literary sense, which is only like saying that modern novel is ignorant in the chemical sense, or the economic sense, or the astronomical sense; but it is not vulgar intrinsically–it is the actual centre of a million flaming imaginations.

Sentiments like these inspired admirers of Chesterton like Marshall McLuhan and Jorge Luis Borges to take seriously the mass entertainments of their respective cultures.

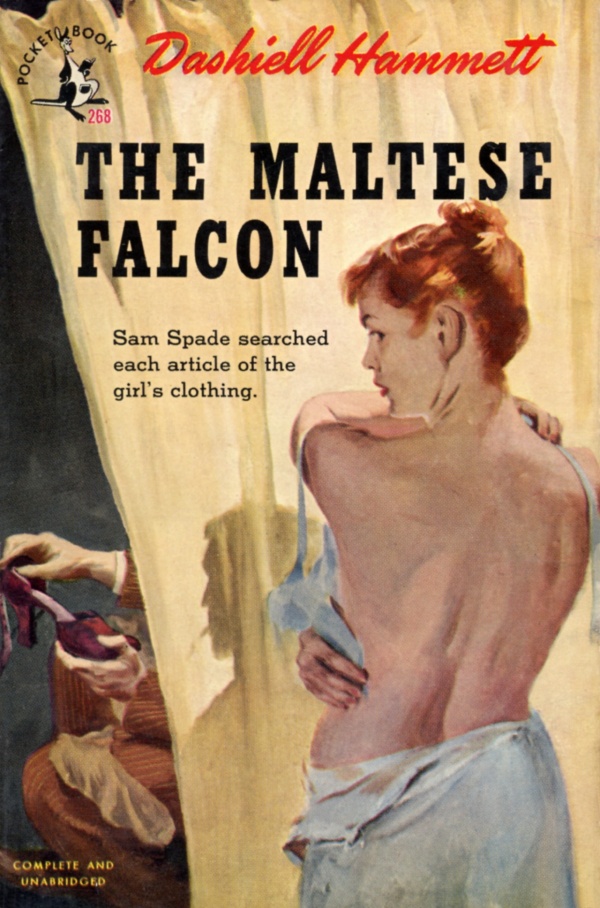

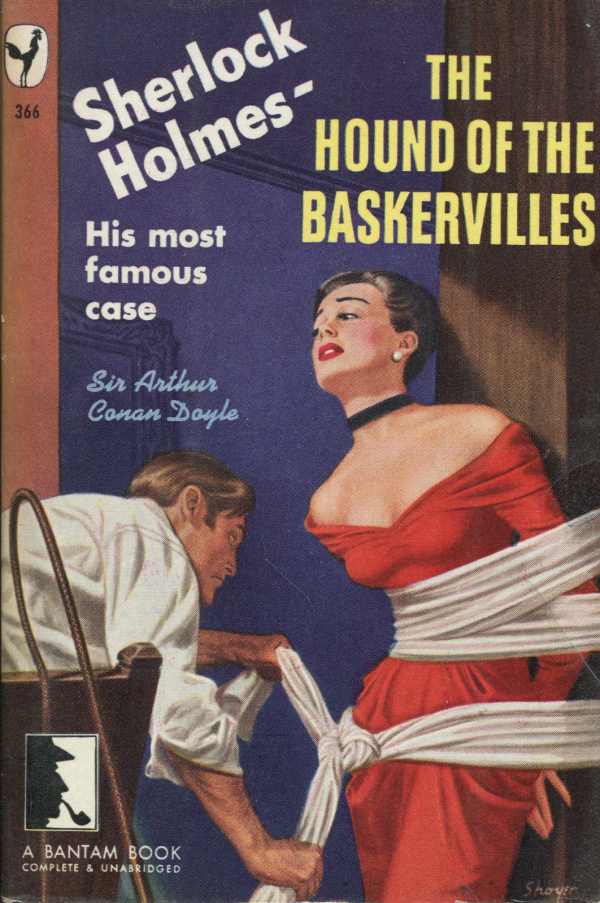

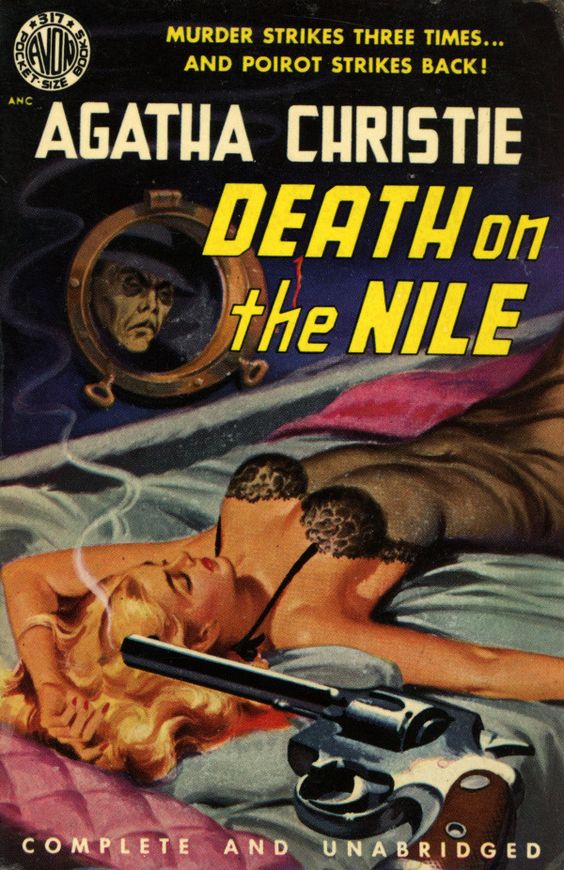

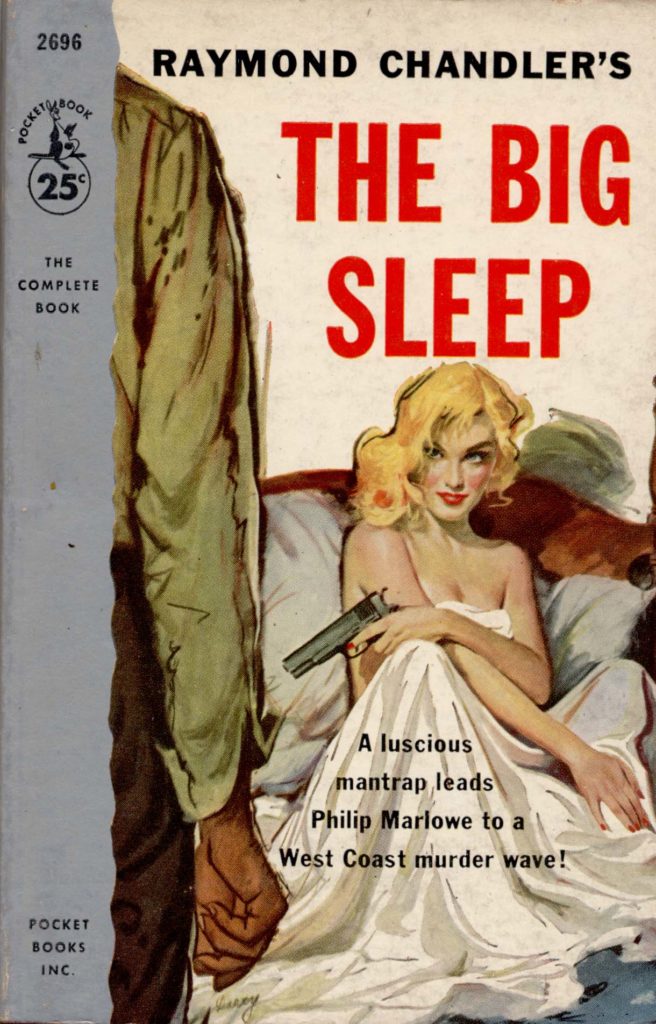

We might apply a Chestertonian appreciation to the book covers here, illustrating detective fiction by such notables as Dashiell Hammett, Arthur Conan Doyle, Agatha Christie, and Raymond Chandler.

Despite the cultural cachet these names bear, they are also writers whose work thrived in the “pulps,” a term denoting, Rebecca Romney writes at Crime Reads, “a wide category that bounds across genres.” Famed detective writers were as likely to be printed in “pulp fiction” magazines and cheap paperback editions as were acclaimed authors like Jules Verne, H.G. Wells, and Edgar Allan Poe. In addition to a number of genre conventions, the “common traits” of pulp fiction “are cheapness, portability, and popularity.”

Detective fiction, whether “literary” or wildly sensational, has always been a popular entertainment, close kin to the “Penny Dreadful,” those cheaply-produced 19th century British novels of adventure and sensation. “Twentieth-century detective novels are intimately tied to the history of the pulps,” writes Romney, which “rely on the erotic for their appeal.” Pulp publications sensationalize in images what may be far more chaste in the text. These “ridiculously sexified” book covers do not bother with coy symbolism or minimalist allusion. They take aim directly at the libido, or, to take Chesterton’s phrase, “the actual centre of a million flaming imaginations.”

The cover of The Maltese Falcon at the top goes out of its way to illustrate “the only sexually scandalous scene of the book, as if it were the single most crucial moment of the entire story.” The cover is pure objectification, and on such grounds we might reasonably object. To do so is to critique an entire mid-twentieth century aesthetic of “exploitation,” a campy style that gleefully titillated audiences who gleefully desired titillation.

The covers date from the mid-thirties to early fifties. All of the typical visual pulp themes are here, which are also typical of detective fiction and noir: the femme fatale (called “a luscious mantrap” on the cover of Raymond Chandler’s The Big Sleep below), in various seductive states of undress; the unsubtle hints of violence and sadomasochism. Such themes in the novels can be overt, implicit, or fully submerged. The focus of these covers turns the tropes into cheap come-ons. In this, perhaps, they do their authors an injustice, but their naked intention is solely to make the sale. What readers do with the books afterward is their own affair.

“These absurd covers,” Romney writes, “speak to the detective novel’s unavoidably shared heritage with other sensational pulp genres, much like the ever-present creepy uncle at Thanksgiving.” As much as quality detective fiction, sci-fi, fantasy, and horror might receive critical praise as high art, they will always be inextricably related to the “vulgar” pleasures of the pulps. To speak of such entertainments as the domain of the lowbrow, the magnanimous Chesterton might say, is only to “mean humanity minus ourselves.” Still, I wonder what Chesterton would have said had his collected Father Brown stories appeared in a pulp version with a nonsensically sexy cover?

Visit Crime Reads to see these covers compared with those of more subtle, and arguably more tasteful, editions.

More pulp covers of classic literature can be found at LitHub.

Related Content:

Raymond Chandler’s Ten Commandments for Writing a Detective Novel

Josh Jones is a writer and musician based in Durham, NC. Follow him at @jdmagness

Leave a Reply