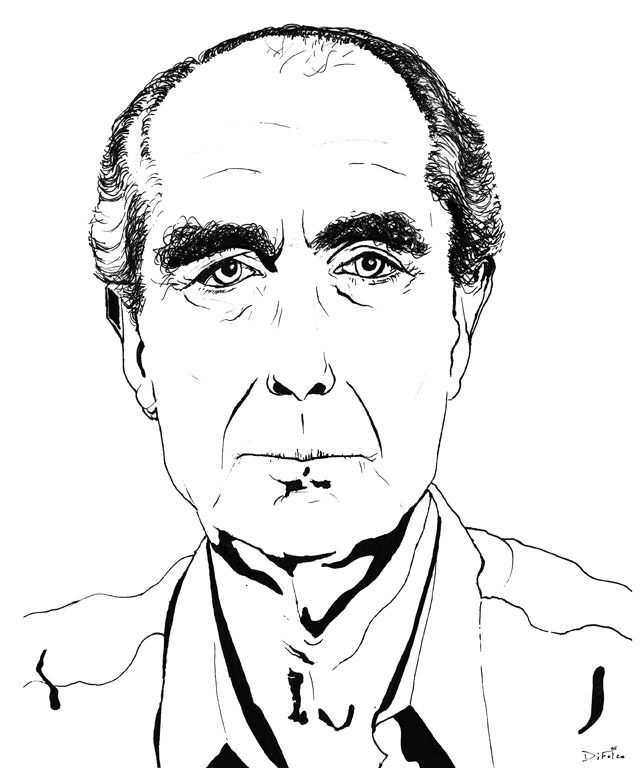

Image by Thierry Ehrmann, via Flickr Commons

We stand at a pivotal time in history, and not only when it comes to presidential politics and other tragedies. The boomer-era artists and writers who loomed over the last several decades—whose influence, teaching, or patronage determined the careers of hundreds of successors—are passing away. It seems that not a week goes by that we don’t mourn the loss of one or another towering figure in the arts and letters. And along with the eulogies and tributes come critical reappraisals of often straight white men whose sexual and racial politics can seem seriously problematic through a 21st century lens.

Surely such pieces are even now being written after the death of Philip Roth yesterday, novelist of, among many other themes, the unbridled straight male Id. From 1969’s sex-obsessed Alexander Portnoy—who masturbates with raw liver and screams at his therapist “LET’S PUT THE ID BACK IN YID!”—to 1995’s aging, sex-obsessed puppeteer Mickey Sabbath, who masturbates over his own wife’s grave, with several obsessive men like David Kepesh (who turns into a breast) in-between, Roth created memorably shocking, frustrated Jewish male characters whose sexuality might generously be described as selfish.

In a New York Times interview at the beginning of this year, Roth, who retired from writing in 2012, addressed the question of these “recurrent themes” in the era of Trump and #MeToo. “I haven’t shunned the hard facts in these fictions of why and how and when tumescent men do what they do, even when these have not been in harmony with the portrayal that a masculine public-relations campaign — if there were such a thing — might prefer.… Consequently, none of the more extreme conduct I have been reading about in the newspapers lately has astonished me.”

The psychological truths Roth tells about fitfully neurotic male egos don’t flatter most men, as he points out, but maybe his depictions of obsessive male desire offer a sobering perspective as we struggle to confront its even uglier and more violent, boundary-defying irruptions in the real world. That said, many a writer after Roth handled the subject with far less humor and comic awareness of its bathos. From where did Roth himself draw his sense of the tragically absurd, his literary interest in extremes of human longing and its often-destructive expression?

He offered one collection of influences in 2016, when he pledged to donate his personal library of over 3,500 volumes to the Newark Public Library (“my other home”) upon his death. Along with that announcement, Roth issued a list of “fifteen works of fiction,” writes Talya Zax at Forward, “he considers most significant to his life.” Next to each title, he lists the age at which he first read the book.

- Citizen Tom Paine by Howard Fast, first read at age 14

- Finnley Wren by Philip Wylie, first read at age 16

- Look Homeward Angel by Thomas Wolfe, first read at age 17

- Catcher in the Rye by J.D. Salinger, first read at age 20

- The Adventures of Augie March by Saul Bellow, first read at age 21

- A Farewell to Arms by Ernest Hemingway, first read at age 23

- The Assistant by Bernard Malamud, first read at age 24

- Madame Bovary by Gustave Flaubert, first read at age 25

- The Sound and the Fury by William Faulkner, first read at age 25

- The Trial by Franz Kafka, first read at age 27

- The Fall by Albert Camus, first read at age 30

- Crime and Punishment by Fyodor Dostoyevsky, first read at age 35

- Anna Karenina by Leo Tolstoy, first read at age 37

- Cheri by Colette, first read at age 40

- Street of Crocodiles by Bruno Schulz, first read at age 41

“It’s worth noting,” Zax points out, “that Roth, who frequently fields accusations of misogyny, included only one female author on the list: Colette.” Make of that what you will. We might note other blind spots as well, but so it is. Should we read Philip Roth? Of course we should read Philip Roth, for his keen insights into varieties of American masculinity, Jewish identity, aging, American hubris, literary creativity, Wikipedia, and so much more besides, spanning over fifty years. Start at the beginning with two of his fist published stories from the late 50s, “Epstein” and “The Conversion of the Jews,” and work your way up to the 21st century.

via The Forward

Related Content:

What Was It Like to Have Philip Roth as an English Prof?

Philip Roth Predicts the Death of the Novel; Paul Auster Counters

Josh Jones is a writer and musician based in Durham, NC. Follow him at @jdmagness

Good piece. Just a quick quibble, Phillip Roth wasn’t a baby boomer. The oldest boomer is in their early seventies right now.

One more nitpick, Mickey Sabbath does not masturbate over his own wife’s grave, he masturbates over his lover Drenka’s grave.

Ah, I misremembered that detail, thanks (impossible, however, to forget the scene).

Quite so. Roth was born in the 1930s, well before the generally accepted start of the Baby Boom in 1944. He was part of the “Silent Generation,” those born in the late 1920s up through World War II. He was old enough to remember the war, which to me is a clear mark of being pre-Boomer.

I was tempted not to continue reading this after the author described Philip Roth as a baby boomer, despite the fact that he was born a full six years before the Second World War! I mean, for Christ’s sake, words and phrases have meanings! They don’t just exist in a vacuum where you can use them to mean anything you like! Anyway, of course, I did read it, because it’s Philip Roth listing 15 books he was influenced by. How could I not? But seriously, maybe get an editor or something?

Until the age of 24, he read only American writers. Later European ones. The older you are, the wiser you are to say.

As an Englishman I have been totally absorbed by the world of Roth and his characters. Jewish life in Newark, the location of such a life in American history and the challenges of living such a life were an alien world to me and I suspect millions of us here in Britain and indeed, the rest of Europe. My first encounter was reading American Pastoral, sometime before 2006; I know this as I began to keep a list of everything I read starting that year. I mention that for two reasons, first because in looking at Roth’s own list I wish I could recall what I had read in my formative years and secondly because I can see that whilst widely read in terms of European literature, the last 12 years has seen me consume more by American authors then any other. To reference some of the earlier comments then, I find that I was likely 43 when I discovered Roth, I was also possessed of similar masculine angst and increasingly so as I age and Roth has provided a voice for that journey. To find that he can speak for and to me, a younger man, from another culture, on another continent, about an unknown existence, simply underscores his greatness in being able to transcend those differences and present the complexity and fallibility of a male mind.