As some of the finest fictional world-builders have understood, few things excite the imagination like a map. And despite the geographical limitation implied by its title, National Geographic’s maps have surveyed the entire globe and beyond. The magazine’s articles have not always presented an enlightened point of view, but for all its historical failings, the richly-illustrated monthly has excelled as a showcase for cartography, over which readers might spend hours, projecting themselves into unknown lands, journeying through the carefully-drawn topographies, cityscapes, and celestial charts.

Started as the official journal of the National Geographic Society, the magazine has amassed a huge, 130-year archive of “editorial cartography,” the National Geographic site writes. “Now, for the first time,” that collection is available online, “every map ever published in the magazine since the first issue of October 1888.”

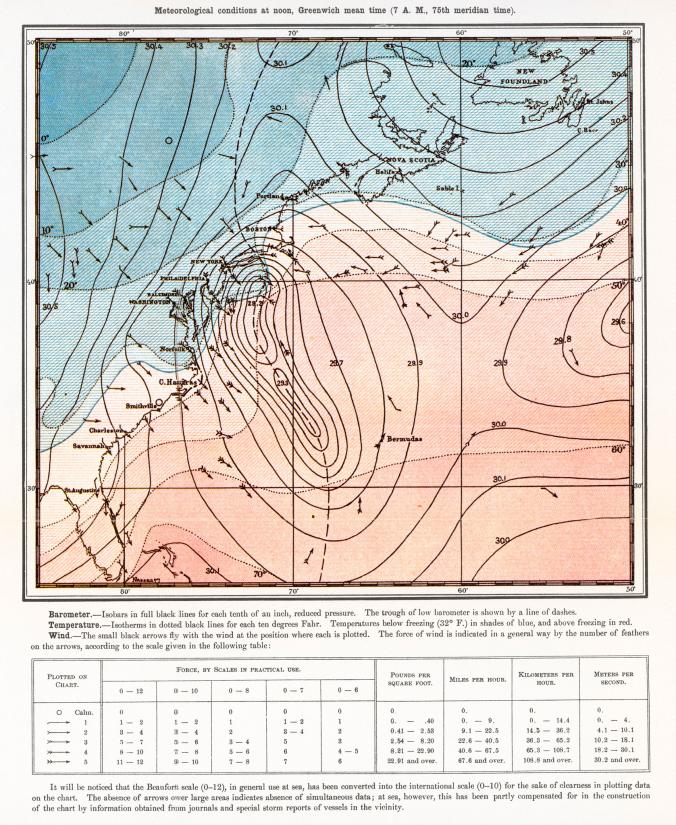

The entire archive is only available to subscribers (however you can find curated selections on the NatGeoMaps Twitter, Instagram, and Facebook accounts), but we can still see an astonishing quality and variety on display in dozens of maps on social media of every conceivable location, topic, and event, beginning with the very first published map, depicting the Great White Hurricane, “one of the most severe blizzards to ever hit the United States” (above)—the “start of a long tradition… of enhancing storytelling with maps.”

As longtime readers of National Geographic well know, the maps—often separable from the magazine in fold-outs suitable for hanging on the wall—function as more than visual aids. They tell their own stories. “A map is able to connect with somebody in a different way than a text will or a photo will,” notes the magazine’s director of cartography Martin Gamache. Maps “engage with a different part of our psyche or our brain.” From its earliest articulation, geography has inclined toward the poetic. The ancient geographer Strabo credited Homer as “the founder of geographical science,” who “reached the utmost limits of the earth, traversing it in his imagination.” Maps present us with a visual poetry often Homeric in its scope.

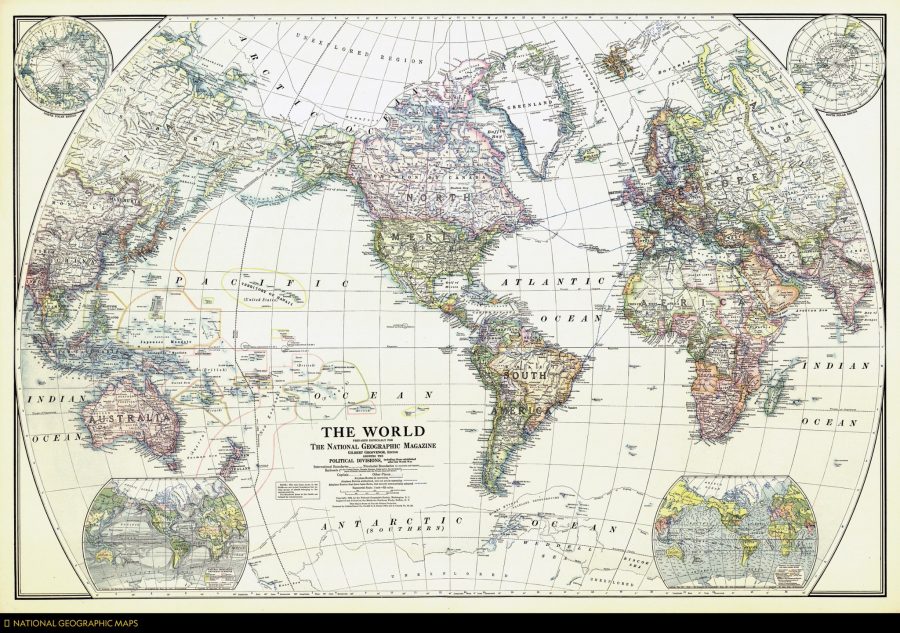

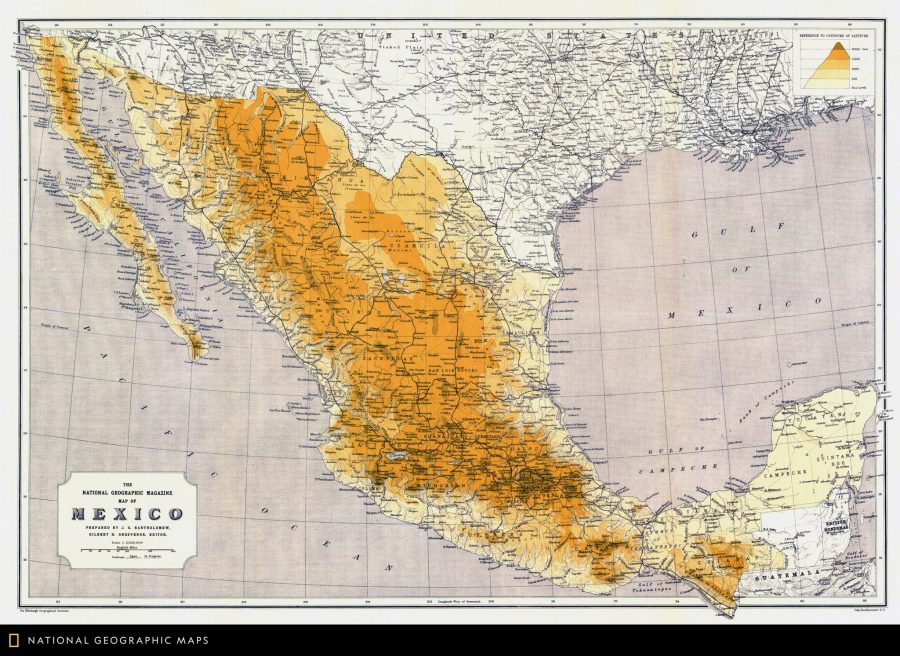

Though so many of these maps are detachable, it often helps to understand the specific context in which they were created, which doesn’t always appear in a self-contained legend. The map above, for example, published in March 1966, shows the Kremlin “in unprecedented detail,” as the magazine’s Twitter account points out: “Soviet regulations prohibited aerial photos, so artists collected diagrams and ground-level photos to draft a sketch that was brought to Moscow and corrected on the spot.” Further up, we see a map of Mexico from May 1914, “one of the first general reference maps of the country” from the National Geographic archive. The map at the top, from the December 1922 issue, is the magazine’s very first published general reference map of the world.

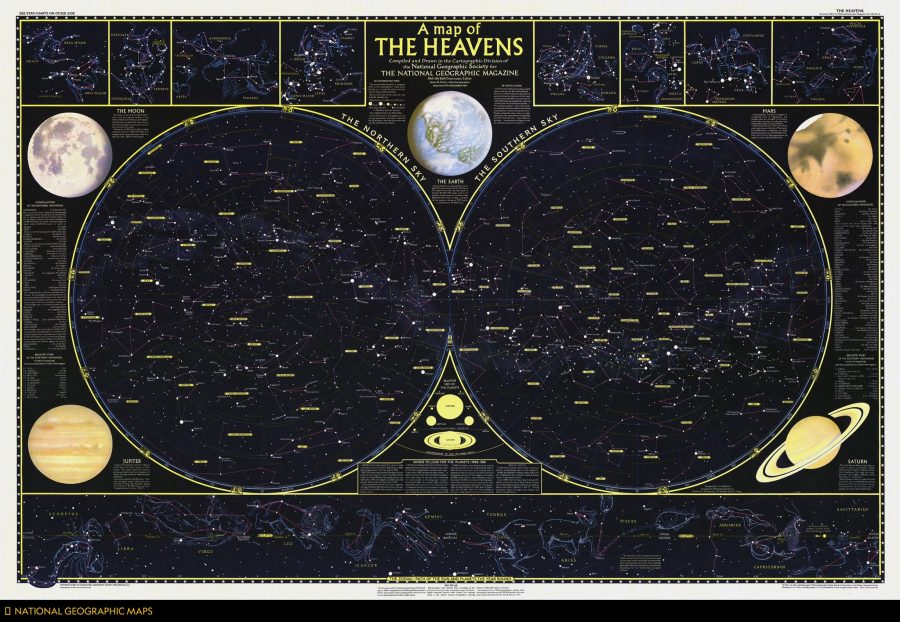

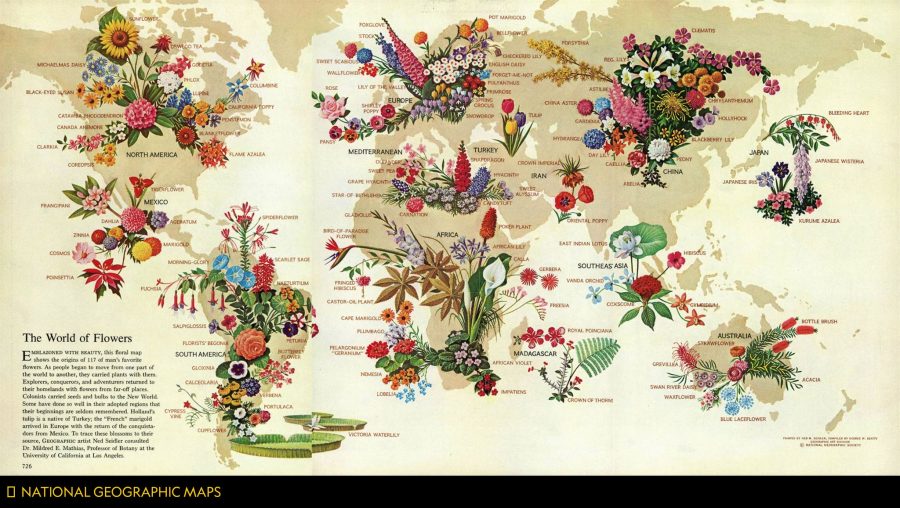

There are maps celestial, as above from 1957, and architectural—such as recent digital recreations of King Tut’s tomb, lately revealed to have no hidden chambers left to explore. Maps of planets beyond the solar system and planets (or “dwarf planets”) within it, such as this first published map of Pluto. Maps of rivers like the Rhine and spectacular natural formations like the Grand Canyon. There are even maps of flowers, like that published below in May 1968, showing “the origins of 117 types of blooms.” Some maps are much less joyous, like this recent series showing what the world might look like if all of the ice melted. Some are purely for fun, like this series on the geography of Star Wars and other fictional franchises.

If we can imagine it, National Geographic suggests, we can map it, and conversely, when we see a map, our imaginations are immediately engaged. Learn more at the NatGeo blog All Over the Map, and connect with many more curated maps from this huge collection at the magazine’s Twitter, Instagram, and Facebook accounts.

Related Content:

A Map Showing How the Ancient Romans Envisioned the World in 40 AD

An Interactive Map Shows Just How Many Roads Actually Lead to Rome

Josh Jones is a writer and musician based in Durham, NC. Follow him at @jdmagness

Hi

Is the map image “World of Flowers” cooyright or can it be used in creative art journals which will be for sale.