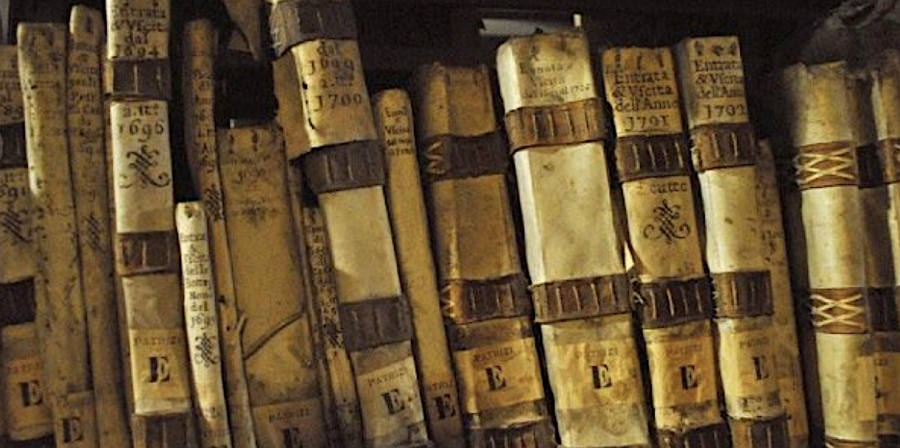

Somewhere within the Vatican exists the Vatican Secret Archives, whose 53 miles of shelving contains more than 600 collections of account books, official acts, papal correspondence, and other historical documents. Though its holdings date back to the eighth century, it has in the past few weeks come to worldwide attention. This has brought about all manner of jokes about the plot of Dan Brown’s next novel, but also important news about the technology of manuscript digitization. It seems a project to get the contents of the Vatican Secret Archives digitized and online has made great progress cracking a problem that once seemed impossibly difficult: turning handwriting into computer-searchable text.

In Codice Ratio is “developing a full-fledged system to automatically transcribe the contents of the manuscripts” that uses not the standard method of optical character recognition (OCR), which looks for the spaces between words, but a new way that can handle connected cursive and calligraphic letters. Their method, in the lingo of the field, “is to govern imprecise character segmentation by considering that correct segments are those that give rise to a sequence of characters that more likely compose a Latin word. We have designed a principled solution that relies on convolutional neural networks and statistical language models.”

This is a job, in other words, for artificial intelligence, but in partnership with human intelligence, a seldom-tapped source of which the scientists behind In Codice Ratio have harnessed: that of high-school students. Their special OCR software, writes the Atlantic’s Sam Kean, works by “dividing each word into a series of vertical and horizontal bands and looking for local minimums—the thinner portions, where there’s less ink (or really, fewer pixels). The software then carves the letters at these joints.” But the software “needs to know which groups of chunks represent real letters and which are bogus,” and so “the team recruited students at 24 schools in Italy to build the projects’ memory banks,” manually separating the letters the system had properly recognized from those over which it had stumbled.

And so the students became the system’s “teachers,” improving its ability to extract the content of handwriting, and not just handwriting but vast quantities of archaic handwriting, with every click they made. The encouraging results thus far mean that it probably won’t be long before large portions of the Vatican Secret Archives (which, contrary to its awkwardly translated name, is such a non-secret it even has its own official web site) will finally become easy to browse, search, copy, paste, and analyze. So they may, in the fullness of time, prove a fruitful resource indeed to writers of Catholicism-centric thrillers like Brown — who, after all, has already gone public with his enthusiasm for manuscript digitization.

Related Content:

Based in Seoul, Colin Marshall writes and broadcasts on cities and culture. His projects include the book The Stateless City: a Walk through 21st-Century Los Angeles and the video series The City in Cinema. Follow him on Twitter at @colinmarshall or on Facebook.

Leave a Reply