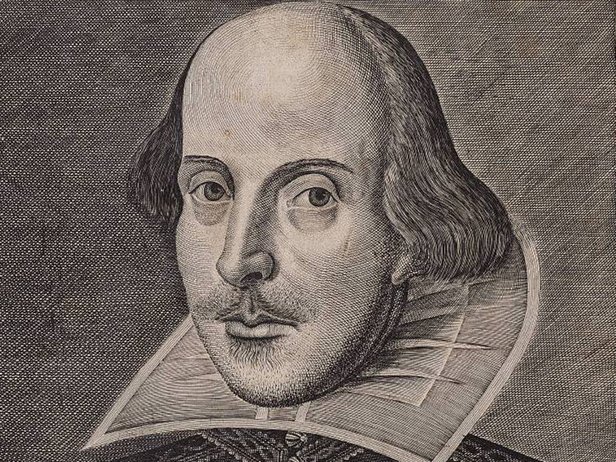

One of the favorite reference books on my shelves isn’t a style guide or dictionary but a collection of insults. And not just any collection of insults, but Shakespeare’s Insults for Teachers, an illustrated guide through the playwright’s barbs and put-downs, designed to offer comic relief to the beleaguered educator. (Books and websites about Shakespeare’s insults almost constitute a genre in themselves.) I refer to this slim, humorous hardback every time discussions of Shakespeare get too ponderous, to remind myself at a glance that what readers and audiences have always valued in his work is its lightning-fast wit and inventiveness.

While perusing any curated selection of Shakespeare’s insults, one can’t help but notice that, amidst the puns and bawdy references to body parts, so many of his wisecracks are about language itself—about certain characters’ lack of clarity or odd ways of speaking. From Much Ado About Nothing there’s the colorful, “His words are a very fantastical banquet, just so many strange dishes.” From The Merchant of Venice, the sarcastic, “Goodly Lord, what a wit-snapper you are!” From Troilus and Cressida, the derisive, “There’s a stewed phrase indeed!” And from Hamlet the subtle shade of “This is the very coinage of your brain.”

Indeed, it can often seem that Shakespeare—if we grant his historicity and authorship—is often writing self-deprecating notes about himself. “It is often said,” writes Fraser McAlpine at BBC America, that Shakespeare “invented a lot of what we currently call the English language…. Something like 1700 [words], all told,” which would mean that “out of every ten words,” in his plays, “one will either have been new to his audience, new to his actors, or will have been passingly familiar, but never written down before.” It’s no wonder so much of his dialogue seems to carry on a meta-commentary about the strangeness of its language.

We have enough trouble understanding Shakespeare today. The question McAlpine asks is how his contemporary audiences could understand him, given that so much of his diction was “the very coinage” of his brain. Lists of words first used by Shakespeare can be found aplently. There’s this catalog from the exhaustive multi-volume literary reference The Oxford English Dictionary, which lists such now-everyday words as “accessible,” “accommodation,” and “addiction” as making their first appearance in the plays. These “were not all invented by Shakespeare,” the list disclaims, “but the earliest citations for them in the OED” are from his work, meaning that the dictionary’s editors could find no earlier appearance in historical written sources in English.

Another shorter list links to an excerpt from Charles and Mary Cowden Clarke’s The Shakespeare Key, showing how the author, “with the right and might of a true poet… minted several words” that are now current, or “deserve” to be, such as the verb “articulate,” which we do use, and the noun “co-mart”—meaning “joint bargains”—which we could and maybe should. At ELLO, or English Language and Linguistics Online, we find a short tutorial on how Shakespeare formed new words, by borrowing them from other languages, or adapting them from other parts of speech, turning verbs into nouns, for example, or vice versa, and adding new endings to existing words.

“Whether you are ‘fashionable’ or ‘sanctimonious,’” writes National Geographic, “thank Shakespeare, who likely coined the terms.” He also apparently invented several phrases we now use in common speech, like “full circle,” “one fell swoop,” “strange bedfellows,” and “method in the madness.” (In another BBC America article, McAlpine lists 45 such phrases.) The online sources for Shakespeare’s original vocabulary are multitude, but we should note that many of them do not meet scholarly standards. As linguists and Shakespeare experts David and Ben Crystal write in Shakespeare’s Words, “we found very little that might be classed as ‘high-quality Shakespearean lexicography’” online.

So, there are reasons to be skeptical about claims that Shakespeare is responsible for the 1700 or more words for which he’s given sole credit. (Hence the asterisk in our title.) As noted, a great many of those words already existed in different forms, and many of them may have existed as non-literary colloquialisms before he raised their profile to the Elizabethan stage. Nonetheless, it is certainly the case that the Bard coined or first used hundreds of words, writes McAlpine, “with no obvious precedent to the listener, unless you were schooled in Latin or Greek.” The question, then, remains: “what on Earth did Shakespeare’s [mostly] uneducated audience make of this influx of newly-minted language into their entertainment?”

McAlpine brings those potentially stupefied Elizabethans into the present by comparing watching a Shakespeare play to watching “a three-hour long, open air rap battle. One in which you have no idea what any of the slang means.” A good deal would go over your head, “you’d maybe get the gist, but not the full impact,” but all the same, “it would all seem terribly important and dramatic.” (Costuming, props, and staging, of course, helped a lot, and still do.) The analogy works not only because of the amount of slang deployed in the plays, but also because of the intensity and regularity of the boasts and put-downs, which makes even more interesting one data scientist’s attempt to compare Shakespeare’s vocabulary with that of modern rappers, whose language is, just as often, the very coinage of their brains.

Related Content:

Do Rappers Have a Bigger Vocabulary Than Shakespeare?: A Data Scientist Maps Out the Answer

What Shakespeare’s English Sounded Like, and How We Know It

Josh Jones is a writer and musician based in Durham, NC. Follow him at @jdmagness.

hhheeeeeyyyy!!!!!

hi ava!!!

Very interesting indeed. Love the fact that Shakespeare is being compared to modern-day rappers. Alas, the man indeed was a lyrical genius and would want to hear an album of his plays set to rap 🎶 music 🎼 or even reggae, reggae-ton, soca or any of the other genres of our time!

Myself and Henry Ford have little in common but we share the view that ‘History is mostly bunkem.’ In other words, we don’t know because we weren’t there. We mythologise. I don’t believe Shakespeare invented anywhere near the number of words attributed to him, though he WAS the first to record them.

I mean, he’s attributed with inventing ‘candle holder’! Do you really think the Tudors had no word for the thing they stood their candle in? “It’s getting dark,can you put a fresh candle in that…you know…that thing we haven’t got a word for.”