The pronouncements of French theorist Jean Baudrillard could sound a bit silly in the early 1990s, when the internet was still in its infancy, a slow, clunky technology whose promises far exceeded what it could deliver. We hoped for the cyberpunk spaces of William Gibson, and got the beep-boop tedium of dial-up. Even so, in his 1991 essay “Simulacra and Science Fiction,” Baudrillard contended that the real and the imaginary were no longer distinguishable, and that the collapse of the distance between them meant that “there is no more fiction.” Or, conversely, he suggested, that there is no more reality.

What seemed a far-fetched claim about the totality of “cybernetics and hyperreality” in the age of AOL and Netscape now sounds far more plausible. After all, it will soon be possible, if it is not so already, to convincingly simulate events that never occurred, and to make millions of people believe they had, not only through fake tweets, “fake news,” and age-old propaganda, but through sophisticated manipulation of video and audio, through augmented reality and the onset of “reality apathy,” a psychological fatigue that overwhelms our abilities to distinguish true and false when everything appears as a cartoonish parody of itself.

Technologist Aviv Ovadya has tried since 2016 to warn anyone who would listen that such a collapse of reality was fast upon us—an “Infocalypse,” he calls it. If this is so, according to Baudrillard, “both traditional SF and theory are destined to the same fate: flux and imprecision are putting an end to them as specific genres.” In an apocalyptic prediction, he declaimed, “fiction will never again be a mirror held to the future, but rather a desperate rehallucinating of the past.” The “collective marketplace” of globalization and the Borgesian condition in which “the map covers all the territory” have left “no room any more for the imaginary.” Companies set up shop expressly to simulate and falsify reality. Pained irony, pastiche, and cheap nostalgia are all that remain.

It’s a bleak scenario, but perhaps he was right after all, though it may not yet be time to despair—to give up on reality or the role of imagination. After all, sci-fi writers like Gibson, Philip K. Dick, and J.G. Ballard grasped long before most of us the condition Baudrillard described. The subject proved for them and many other late-20th century sci-fi authors a rich vein for fiction. And perhaps, rather than a great disruption—to use the language of a start-up culture intent on breaking things—there remains some continuity with the naïve confidence of past paradigms, just as Newtonian physics still holds true, only in a far more limited way than once believed.

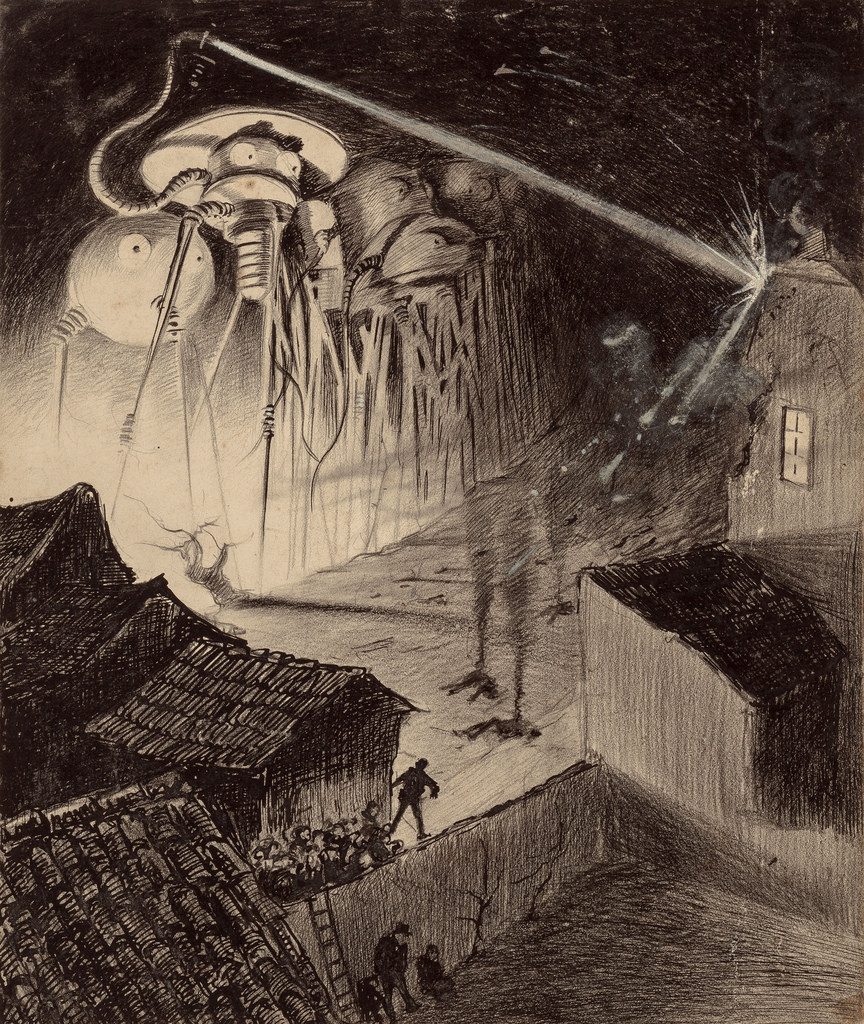

Isaac Asimov’s short essay “The Relativity of Wrong” is instructive on this last point. Maybe the theory of “hyperreality” is right, in some fashion, but also incomplete: a future remains for the most visionary creative minds to discover, as it did for Asimov’s “psychohistorian” Hari Seldon in The Foundation Trilogy. You can hear a BBC dramatization of that groundbreaking fifties masterwork in the 47-hour science fiction playlist above, along with readings of classic stories—like Orson Welles’ infamous radio broadcast of H.G. Wells’ War of the Worlds (and an audiobook of the same read by English actor Maxwell Caulfield). From Jules Verne to H.P. Lovecraft to George Orwell; from the mid-fifties time travel fiction of Andre Norton to the 21st-century time-travel fiction of Ruth Boswell….

We’ve even got a late entry from theatrical prog rock mastermind Rick Wakeman, who followed up his musical adaptation of Journey to the Centre of the Earth with a sequel he penned himself, recorded in 1974, and released in 1999, called Return to the Centre of the Earth, with narration by Patrick Stewart and guest appearances by Ozzy Osbourne, Bonnie Tyler, and the Moody Blues’ Justin Hayward. Does revisiting sci-fi, “weird fiction,” and operatic concept albums of the past constitute a “desperate rehallucinating” of a bygone “lost object,” as Baudrillard believed? Or does it provide the raw material for today’s psychohistorians? I suppose it remains to be seen; the future—and the future of science fiction—may be wide open.

The 47-hour science fiction playlist above will be added to our collection of 900 Free Audio Books.

Related Content:

Free: Isaac Asimov’s Epic Foundation Trilogy Dramatized in Classic Audio

Free: 355 Issues of Galaxy, the Groundbreaking 1950s Science Fiction Magazine

Josh Jones is a writer and musician based in Durham, NC. Follow him at @jdmagness

Several stories show: “Chapter one” by Issac Asimov, or “Chapter one” by HG Wells. Please rectify missing titles. thanks.

Several Titles are missing: There is “Chapter one, chapter two, etc” by HG Wells and “Episode one, etc” by Issac Asimov. Please rectify. Thanks.