Each time I sit through the end credits of a film, I think about how weird auteur theory is—that a work of cinema can be primarily thought of the singular vision of the director. Typical examples come from artier fare than the usual Hollywood blockbuster in which crews of thousands of stuntpeople, special effects technicians, and animators (and several dozen “producers”) make essential contributions. In the case of, say, David Lynch or Wes Anderson—or earlier directors like Godard or Kubrick—one can’t deny the evidence of a singular mind at work. Even so, we tend to elevate directors to the status of godlike artificers, surrounded by a few angelic helpers behind the camera and a few star actors in front of it. Everyone else is an extra, including, very often, the actual writers of a film.

Of course, the notion of the auteur comes from the general theory of authorship that identifies literary works as the product of a single intellect. French theorists like Michel Foucault and Roland Barthes have cast suspicion on this idea. When it comes to writing from the manuscript age, hundreds or thousands of years old, it can be next to impossible to identify the author of a work.

Many an ancient work comes down to us as the product of “Anonymous.” In the case of the major Greek epics, The Odyssey and The Iliad, we have a name, Homer, that most classics scholars treat as a convenient placeholder. As a University of Cincinnati classics site notes, “Homer” could stand for “a group of poets whose works on the theme of Troy were collected.”

Though written references to Homer date back to the sixth century B.C., giving credence to the historical existence of the legendary blind poet, he might have been more director than author, bringing together into a coherent whole the labor of hundreds of different storytellers. For historian Adam Nicolson, author of Why Homer Matters, “it’s a mistake to think of Homer as a person. Homer is an ‘it.’ A tradition. An entire culture coming up with ever more refined and ever more understanding ways of telling stories that are important to it. Homer is essentially shared.” The narrative poetry attributed to Homer, Nicolson suggests, might go back a thousand years before the poet supposedly put it to papyrus.

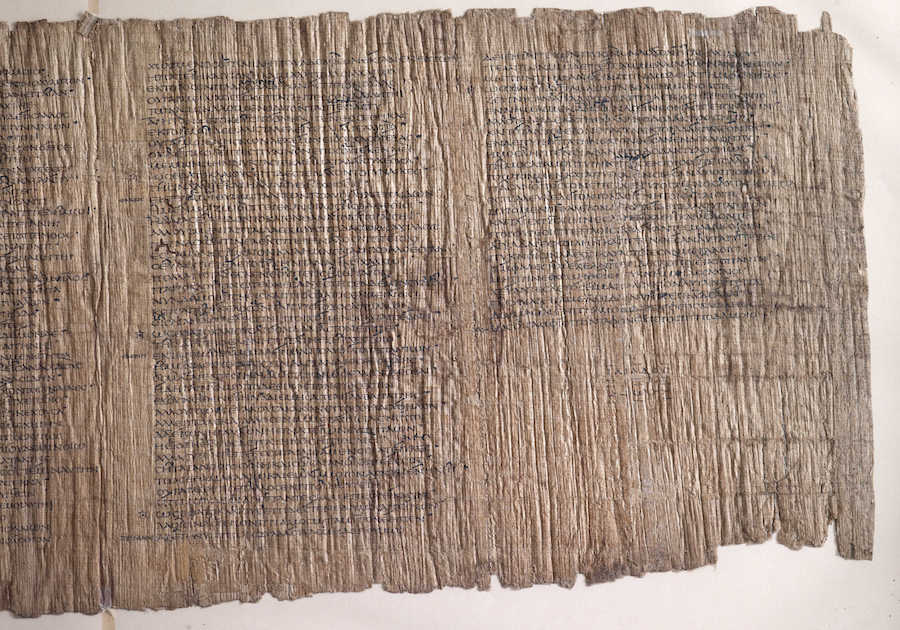

You can read this National Geographic interview with Nicolson (or buy his book) to follow the argument. It isn’t particularly original—as Daniel Mendelsohn writes at The New Yorker, “the dominant orthodoxy” for over a hundred years “has been that The Iliad evolved over centuries before finally being written down” sometime around 700 B.C. We have no manuscripts from that early period, and no one knows how much the poem evolved through scribal errors in the transmission from manuscript to manuscript over centuries. This is one of many questions literary historians ask when they approach papyri like that at the top—an excerpt from the so-called “Bankes Homer,” the most well-preserved specimen of a portion of The Iliad, containing Book 24, lines 127–804, and dating from circa 150 C.E.

Purchased in Egypt in 1821 by Egyptologist William John Bankes, and acquired by an adventurer named Giovanni Finati on the island of Elephantine, the papyrus scroll, which you can see in full and in high resolution at the British Library site, was created like most other “literary papyri” for hundreds of years. As the British Library describes the process:

Professional scribes made copies from exemplars at the request of clients, transcribing by hand, word by word, letter by letter. Until around the 2nd century CE these manuscript books took the form of rolls composed of papyrus sheets pasted one to the other in succession, often over a considerable length.

In addition to the text itself, notes the site History of Information, the manuscript contains “breathing marks and accents made by an ancient diorthotesor ‘corrector’ to show correct poetic pronunciation.” The ancient practice of “correcting” was a pedagogical technique used for training students to properly read the text. Likely for hundreds of years before there was a text, the poem would be committed to memory, and recited by anonymous bards all over the Greek-speaking world, probably changing in the telling to suit the tastes and biases of different audiences. Who can say how many, if any, of those ancient bards bore the name “Homer”?

Again you can see the Bankes Homer in high resolution here.

Related Content:

Hear What Homer’s Odyssey Sounded Like When Sung in the Original Ancient Greek

Josh Jones is a writer and musician based in Durham, NC. Follow him at @jdmagness

Leave a Reply