When you hear the phrase Art of Noise, surely you think of the sample-based avant-garde synth outfit whose instrumental hit “Moments in Love” turned the sound of quiet storm adult contemporary into a hypnagogic chill-out anthem? And when you hear about “noise music,” surely you think of the dramatic post-industrial cacophony of Einstürzende Neubauten or the deconstructed guitar rock of Lightning Bolt?

But long before “noise” became a term of art for rock critics, before the recording industry existed in any recognizably modern form, an Italian futurist painter and composer, Luigi Russolo, invented noise music, launching his creation in 1913 with a manifesto called The Art of Noises.

“In antiquity,” he writes (in Robert Filliou’s translation), “life was nothing but silence.” After presenting an almost comically brief history of sound and music coming into the world, Russolo then declares his thesis, in bold:

Noise was really not born before the 19th century, with the advent of machinery. Today noise reigns supreme over human sensibility…. Nowadays musical art aims at the shrillest, strangest and most dissonant amalgams of sound. Thus we are approaching noise-sound. This revolution of music is paralleled by the increasing proliferation of machinery sharing in human labor.

Not quite so radical as one might think, but bear in mind, this is 1913, the year Stravinsky’s “The Rite of Spring” provoked a riot in Paris upon its debut. Russolo took an even more shocking swerve away from tradition. Pythagorean theory had stifled creativity, he alleged, “the Greeks… have limited the domain of music until now…. We must break at all cost from this restrictive circle of pure sounds and conquer the infinite variety of noise-sounds.”

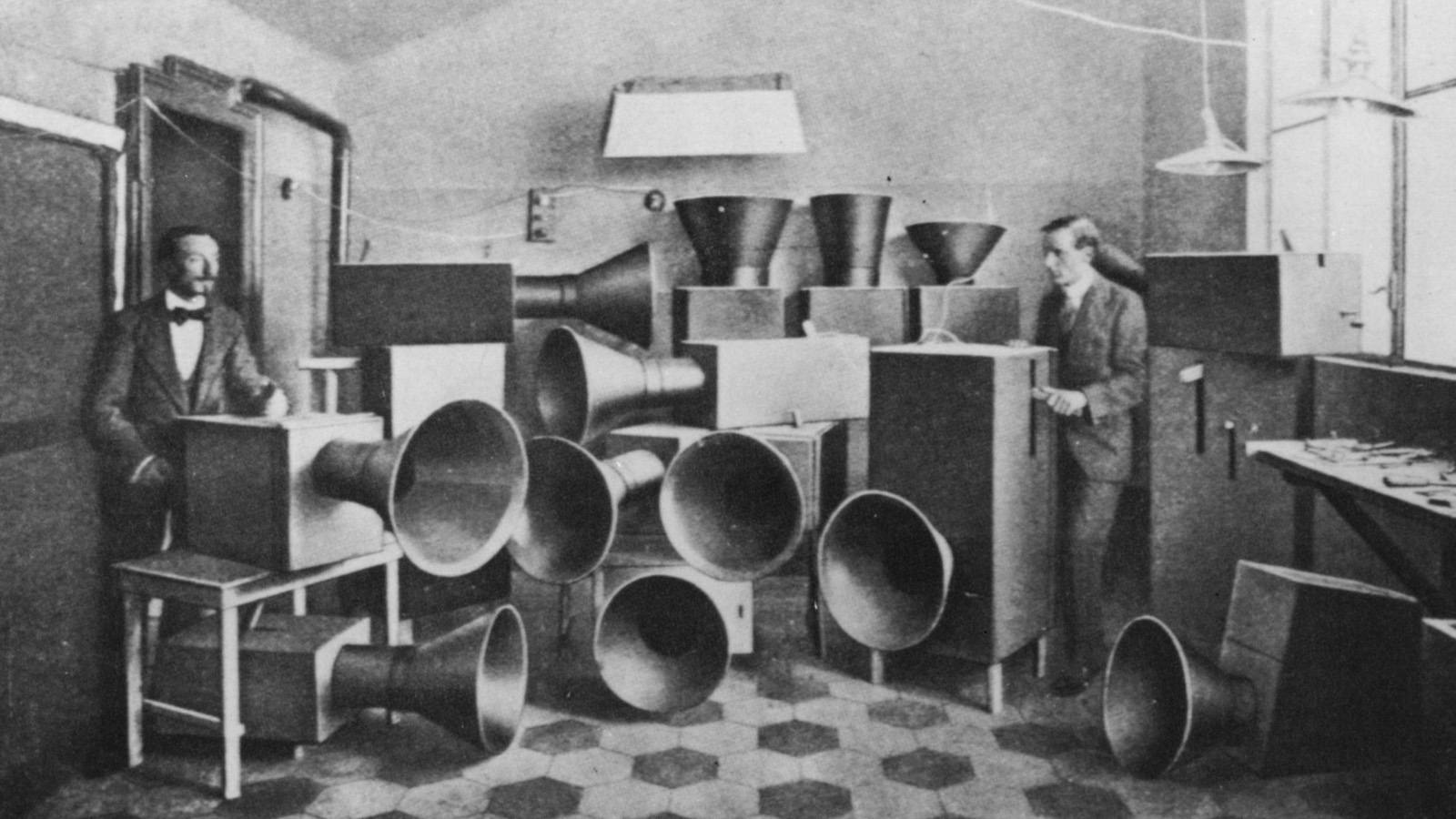

To accomplish his grand objective, the experimental artist created his own series of instruments, the Intonarumori, “acoustic noise generators,” writes Thereminvox, that could “create and control in dynamic and pitch several different types of noises.” Working long before digital samplers and the electronic gadgetry used by industrial and musique concrete composers, Russolo relied on purely mechanical devices, though he did make several recordings as well from 1913 to 1921. (Hear “Risveglio Di Una Città” from 1913 above, and many more original recordings as well as new Intonarumori compositions, at Ubuweb.)

Russolo’s musical contraptions, 27 different varieties, were each named “according to the sound produced: howling, thunder, crackling, crumpling, exploding, gurgling, buzzing, hissing, and so on.” (Stravinsky was apparently an admirer.) You can see reconstructions at the top of the post in a 2012 exhibition at Lisbon’s Museu Coleção Berardo. Many of his own compositions feature string orchestras as well. Russolo introduced his new instrumental music over the course of a few years, debuting an “exploder” in Modena in 1913, staging concerts in Milan, Genoa, and London the following year, and in Paris in 1921.

One 1917 concert apparently provoked explosive violence, an effect Russolo seemed to anticipate and even welcome. The Art of Noise derived its influence from every sound of the industrial world, “and we must not forget the very new noises of Modern Warfare,” he writes, quoting futurist poet Marinetti’s joyful descriptions of the “violence, ferocity, regularity, pendulum game, fatality” of battle. His noise system, which he enumerates in the treatise, also consists of “human voices: shouts, moans, screams, laughter, rattlings, sobs….” It seems that if he didn’t supply these onstage, he was happy for the audience to do so.

After Russolo’s first Art of Noise concert in 1913, Marinetti violently defended the instruments against assaults from those whom the composer called “passé-ists.” Other receptions of the strange new form were more enthusiastically positive. Nonetheless, notes a 1967 “Great Bear Pamphlet” that reprints The Art of Noises, the effects aren’t exactly what Russolo intended: “Listening to the harmonized combined pitches of the bursters, the whistlers, and the gurglers, no one remembered autos, locomotives or running waters; one rather experienced an intense emotion of futurist art, absolutely unforeseen and like nothing but itself.”

Related Content:

Josh Jones is a writer and musician based in Durham, NC. Follow him at @jdmagness

Glad you mentioned Einstürzende Neubauten in context of Russolo. This German experimental band actually reconstructed Russolos Intonarumori in their wonderful music video “Blume”:

https://vimeo.com/36592054