When Miles Davis attended a White House dinner in 1987, he was asked what he had done to deserve to be there. No modest man, Davis, he responded “Well, I’ve changed music five or six times.”

Is it bragging when it’s absolutely true? In this recent Spotify playlist, Steve Henry takes on the Miles Davis discography in roughly a chronological order, a stunning 569 songs and 65 hours of music. That makes that, what, over 90 tracks per revolution in music?

Technically, Davis’ first recorded appearance was as a member of Charlie Parker’s quintet in 1944, and his first as a leader was a 1946 78rpm recording of “Milestones” on the Savoy label. But this playlist starts with the 1951 Prestige album The New Sounds (which later made up the first side of Conception). By this time, Davis had taken the jaunty bebop of mentor and idol Parker and helped create a more relaxed style, a “cool” jazz that would come to dominate the 1950s. Privately he swung between extremes: a health nut who got into boxing, or a heroin addict and hustler/pimp, and he would oscillate between health and illness for the rest of his life.

During the 1950s however, he also created some of his most stunning classics, first for Prestige and Blue Note, where he developed the style to be known as “hard bop; then for Columbia, a label relationship that would result in some of his most revolutionary music. (Note: to get out of his Prestige contract that wanted four more albums out of him, Davis and his Quintet booked two session dates and recorded four albums worth of material, the Cookin’ Relaxin’ Workin’ and Steamin’ albums that in no way sounds like an obligation.)

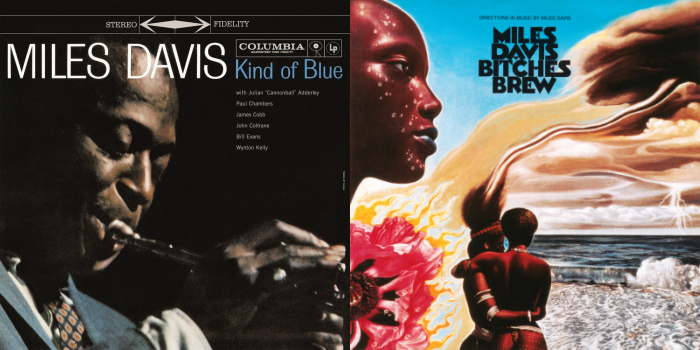

At Columbia, Davis made history with 1959’s Kind of Blue, considered by many as one of the greatest jazz albums of all time, along with his collaborations with arranger Gil Evans (Sketches of Spain, Porgy and Bess, Miles Ahead). After a lull in the mid-‘60s where the music press expected either a resurgence or a tragic end, Davis returned with second quintet (Wayne Shorter, Herbie Hancock, Ron Carter, Tony Williams) for another run of albums in his then “time, no changes” free jazz style, including Miles Smiles, Sorcerer, and Filles de Kilimanjaro.

But none of those prepared anybody for the giant leap beyond jazz itself into proto-ambient with In a Silent Way and the menacing misterioso-funk of Bitches Brew of 1970. Davis had watched rock and funk go from teenager pop music at the beginning of the decade to literally changing the world. He responded by creating one of the densest, weirdest albums which both owed some of its sound to rock and at the same time refuted almost everything about the genre (as well as the history of jazz). He was 44 years old.

His band members went on to shape jazz in the ‘70s: Wayne Shorter and Joe Zawinul formed Weather Report; John McLaughlin formed the Mahavishnu Orchestra; Herbie Hancock, although already established as a solo artist, brought forth the Headhunters album; Chick Corea helped form Return to Forever.

As for Davis, he delved deeper into funk and fusion with a series of albums, including On the Corner, that would go unappreciated at the time, but are now seen as influential in the world of hip hop and beyond. By the ‘80s, after a few years where he just disappeared into reclusion, he returned with some final albums that are all over the map: covering pop hits by Cyndi Lauper and Michael Jackson much in the same way that Coltrane covered The Sound of Music; experimental soundtracks; and experimenting with loops, sequencers, beats, and hip hop. Having struggled with illness and addiction all his life, he passed away at 65 years old in 1991, leaving behind this stunning discography, still offering up surprises to those looking to explore his legacy.

Related Content:

The Night When Miles Davis Opened for the Grateful Dead in 1970: Hear the Complete Recordings

Ted Mills is a freelance writer on the arts who currently hosts the artist interview-based FunkZone Podcast and is the producer of KCRW’s Curious Coast. You can also follow him on Twitter at @tedmills, read his other arts writing at tedmills.com and/or watch his films here.

Fine writing en brevis of a complex man with an extraordinary claim on musical history. He was the Black Bach for sure. Well done, sir!

This quote misses the culmination of Miles.….

“As for Davis, he delved deeper into funk and fusion with a series of albums, including On the Corner, that would go unappreciated at the time, but are now seen as influential in the world of hip hop and beyond. By the ‘80s, after a few years where he just disappeared into reclusion, he returned with some final albums that are all over the map: covering pop hits by Cyndi Lauper”

I think the most important works of the deeper into funk and fusion, are the studio “Get up With It”, and the incredible live albums from a day in Osaka, Agharta and Pangea.

Here he honed the immense jazz septet, Cosey on guitar, Sonny Fortune on flute and saxes. The Michael Henderson bass is wonderful, and under appreciated, as well as Fosters impeccable swing and back beats for Miles. Miles floats in and out speaking with the whaah pedal in some secret language. Miles also plays organ, what every trumpeter wants, to play chords.

As regarding the post Miles work of his 2nd great quintet members, the failure to mention Tony William’s group Lifetime which included a young John McLaughlin, is glaring.Miles is generally credited with starting “fusion” but a listen to Lifetimes “Experiences” before Bitches Brew was recorded will dispell that notion.

Thanks for the responses all. It’s daunting to write up something about one of the most important artists of the 20th century in a short period of time, so if I just cover a fraction well that’s an achievement.

This time round, I was impressed with how many of his “eras” are concentrated sessions that then sustain the record companies for numerous releases. If this was any other artist it would be barrel-scraping, but for Miles, each release is amazing.

Miles Davis was a legend. Thanks for compiling this playlist. It’s a tribute to this great artist

The playlist is far from being a complete chronological discography of Miles Davis, even considering only his studio recordings as a bandleader. To begin with, the first track on the playlist is Odjenar, recorded in March 1951. At that time, Davis had more than 20 tracks recorded as a bandleader already and many many more as a sessionist.

An alternative, probably more accurate, way to create a chronological list is to consider when the album was recorded instead of when it was released. The difference is huge in some cases, e.g. “Steamin’ ” was recorded in 1956, but for commercial reasons it was released in 1961. Miles was artistically in a completely different place in ’56 vs ’61 after Milestones and Kind of Blue.

For a much more accurate chronological playlist, take a look at this one:

https://open.spotify.com/playlist/5PRM6tKfPgrskP0rWwXsXP

And while you listen, you can follow this Google Spreadsheet with all the details of every recording Session:

https://docs.google.com/spreadsheets/d/1Scj-3StQFtIoY6Db807HGb1KFeWLogb3RobFZ6biqi4/edit?usp=sharing