It takes no small amount of inquiry, from no few angles, to truly understand a form of art. This goes even more so for forms of art with which most of us in the 21st century have little direct experience. Take, for example, the illuminated manuscript: its history stretches back to the fifth century and it has arguably shaped all the forms of visual-textual storytelling we enjoy today, yet surely not one of a million of us understands how the artisans that made them did it.

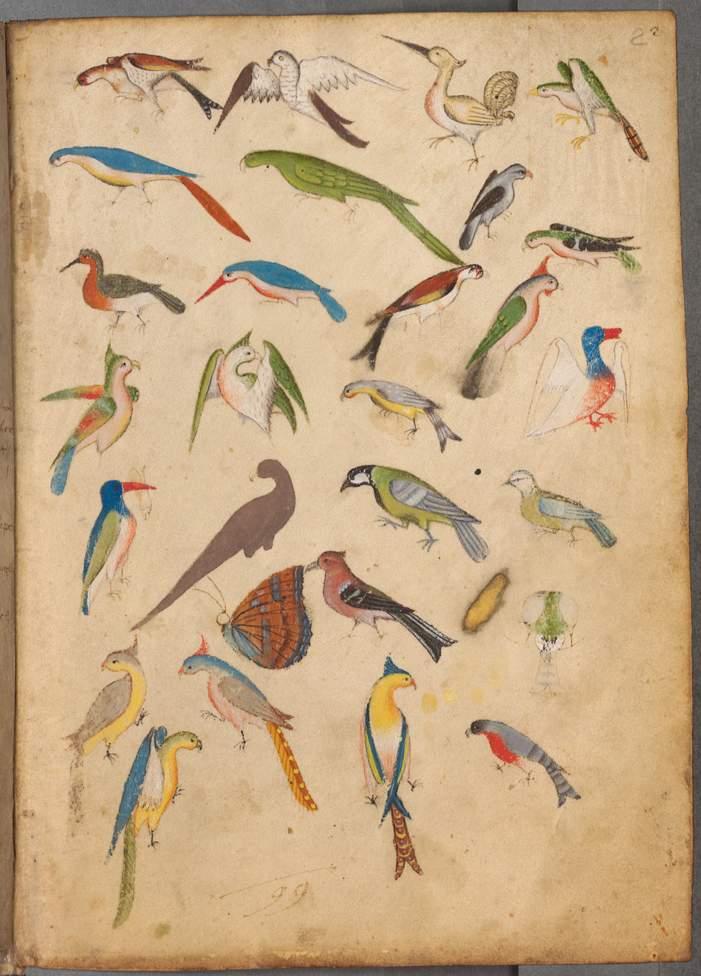

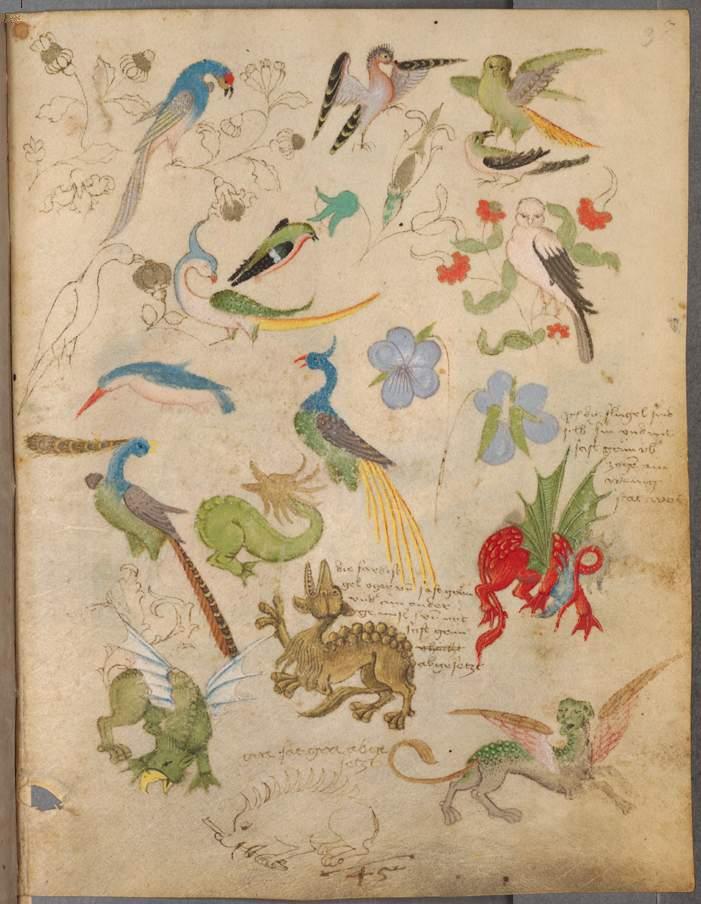

The Public Domain Review did their bit to correct this when they posted the illuminated sketchbook of Stephan Schriber, a series of pages dating from 1494 in which “ideas and layouts for illuminated manuscripts were tried out and skills developed” by the author, a monk in the southwest of Germany. “The monk-artist produced this sketchbook at the tail end of the 1,000-year age of illuminated manuscripts,” write’s Slate’s Rebecca Onion, “a type of book production that was to die out as the Renaissance moved forward and the printing press took over.”

As printed books began to displace illuminated manuscripts, the production of the latter went commercial, no longer produced only by the hands of individual monks. But some of those monks, like Schriber, kept up their dedication to the craft: “These pages show an artist trying out animal motifs, practicing curlicued embellishments, and drafting beautiful presentations of the capital letters that would begin a section, page, or paragraph.”

BibliOdyssey points out that the book, “dedicated to Count Eberhard (Eberhard the bearded, later first Duke) of Württemberg,” appears to be “a manual of templates and/or a practice book containing partially completed sketches, painted and calligraphy initals, stylised floral decorative motifs, plant foliage tendrils, fantastic beast border drolleries” — yes, a real term from the field of illuminated manuscripts — “together with some gold and silver illumination work.”

You can browse more images from Schriber’s sketchbook at this Flickr account, or you can have a look at each and every page at the Munich DigitiZation Center. The images repay close study not just for their own beauty, but for what their seemingly deliberate incompleteness reveals about how a master of manuscript illuminations would go about composing their art. Even the creation of a form whose heyday passed more than half a millennium ago has something to teach us today.

via The Public Domain Review/Slate

Related Content:

1,600-Year-Old Illuminated Manuscript of the Aeneid Digitized & Put Online by The Vatican

Wonderfully Weird & Ingenious Medieval Books

1,000-Year-Old Illustrated Guide to the Medicinal Use of Plants Now Digitized & Put Online

Based in Seoul, Colin Marshall writes and broadcasts on cities and culture. His projects include the book The Stateless City: a Walk through 21st-Century Los Angeles and the video series The City in Cinema. Follow him on Twitter at @colinmarshall or on Facebook.

Thanks to all those faceless people who make digitized images available to everyone. You are my heroes.

Just a simple “Thank You”.