Every musician has some basic sense of how math and music relate conceptually through geometry, in the circular and triadic shapes formed by clusters of notes when grouped together in chords and scales. The connections date back to the work of Pythagoras, and composers who explore and exploit those connections happen upon profound, sometimes mystical, insights. For example, the two-dimensional geometry of music finds near-religious expression in the compositional strategies of John Coltrane, who left behind diagrams of his chromatic modulation that theorists still puzzle over and find inspiring. It will be interesting to see what imaginative composers do with a theory that extends the geometry of music into three—and even four (!)—dimensions.

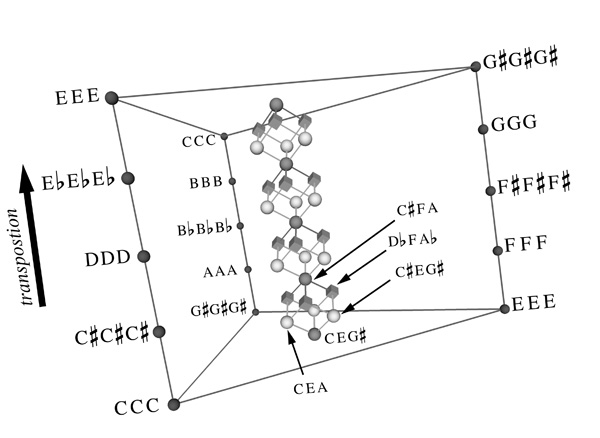

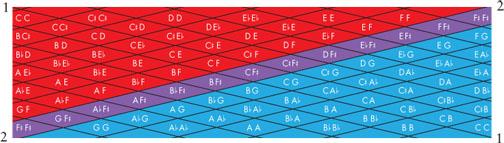

Pioneering Princeton University music theorist and composer Dmitri Tymoczko has made discoveries that allow us to visualize music in entirely new ways. He began with the insight that two-note chords on the piano could form a Möbius strip, as Princeton Alumni Weekly reported in 2011, a two-dimensional surface extended into three-dimensional space. (See one such Möbius strip diagram above.) “Music is not just something that can be heard, he realized. It has a shape.”

He soon saw that he could transform more complex chords the same way. Three-note chords occupy a twisted three-dimensional space, and four-note chords live in a corresponding but impossible-to-visualize four-dimensional space. In fact, it worked for any number of notes — each chord inhabited a multidimensional space that twisted back on itself in unusual ways — a non-Euclidean space that does not adhere to the classical rules of geometry.

Tymoczko discovered that musical geometry (as Coltrane—and Einstein—had earlier intuited) has a close relationship to physics, when a physicist friend told him the multidimensional spaces he was exploring were called “orbifolds,” which had found some application “in arcane areas of string theory.” These discoveries have “physicalized” music, providing a way to “convert melodies and harmonies into movements in higher dimensional spaces.”

This work has caused “quite a buzz in Anglo-American music-theory circles,” says Princeton music historian Scott Burnham. As Tymoczko puts it in his short report “The Geometry of Musical Chords,” the “orbifold” theory seems to answer a question that occupied music theorists for centuries: “how is it that Western music can satisfy harmonic and contrapuntal constraints at once?” On his website, he outlines his theory of “macroharmonic consistency,” the compositional constraints that make music sound “good.” He also introduces a software application, ChordGeometries 1.1, that creates complex visualizations of musical “orbifolds” like that you see above of Chopin supposedly moving through four-dimensions.

The theorist first published his work in a 2006 issue of Science, then followed up two years later with a paper co-written with Clifton Callendar and Ian Quinn called “Generalized Voice-Leading Spaces” (read a three-page summary here). Finally, he turned his work into a book, A Geometry of Music: Harmony and Counterpoint in the Extended Common Practice, which explores the geometric connections between classical and modernist composition, jazz, and rock. Those connections have never been solely conceptual for Tymoczko. A longtime fan of Coltrane, as well as Talking Heads, Brian Eno, and Stravinsky, he has put his theory into practice in a number of strangely moving compositions of his own, such as The Agony of Modern Music (hear movement one above) and Strawberry Field Theory (movement one below). His compositional work is as novel-sounding as his theoretical work is brilliant: his two Science publications were the first on music theory in the magazine’s 129-year history. It’s well worth paying close attention to where his work, and that of those inspired by it, goes next.

via Princeton Alumni Weekly/@dark_shark

Related Content:

The Musical Mind of Albert Einstein: Great Physicist, Amateur Violinist and Devotee of Mozart

Josh Jones is a writer and musician based in Durham, NC. Follow him at @jdmagness

axis of conscienceness and infinite variability touches upon our spirit and it’s ability and need of awareness. this observation is wonderful and begins to address the human depth of not only experience, but creative energy. Once John Cage told my group (the Xperimental Chorus conducted by Hermann LeRoux, SF Conservatory of Music) “remember — energy us form”.