Some writers are restless by nature, roaming like Ernest Hemingway or Henry Miller, settling nowhere and everywhere. Others are homebodies, like William Faulkner and Virginia Woolf. Their fiction reflects their desire to nest in place. Strolling the grounds of Faulkner’s Rowan Oak one sweltering summer, I swear I saw the author round a corner of the house, lost in thought and wearing riding clothes. Visitors to Virginia Woolf’s home in the village of Rodmell in East Sussex have surely had similar visions.

Woolf’s home contains her writing life within the lush garden grounds and cottage walls of the 17th century Monk’s House—Virginia and Leonard’s retreat, then permanent home, from 1919 until her suicide by drowning in the nearby River Ouse in 1941.

Even in death she belonged to the house; Leonard buried her ashes beneath an elm in the Monk’s House garden. Although Leonard was the gardener, “there are very few entries” in Virginia’s diary “which do not mention the garden.”

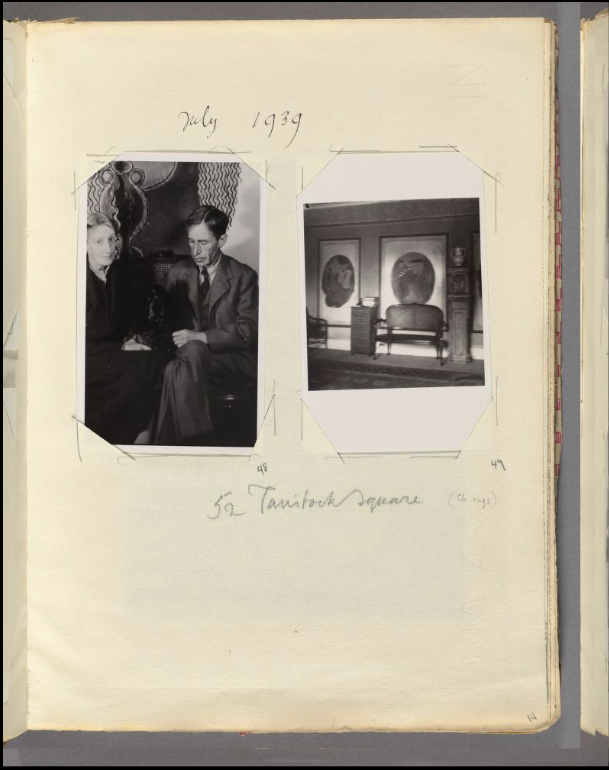

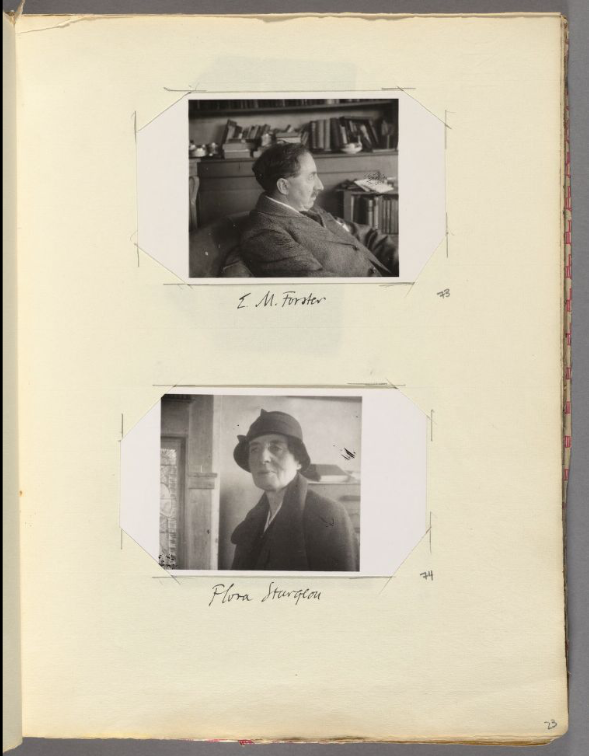

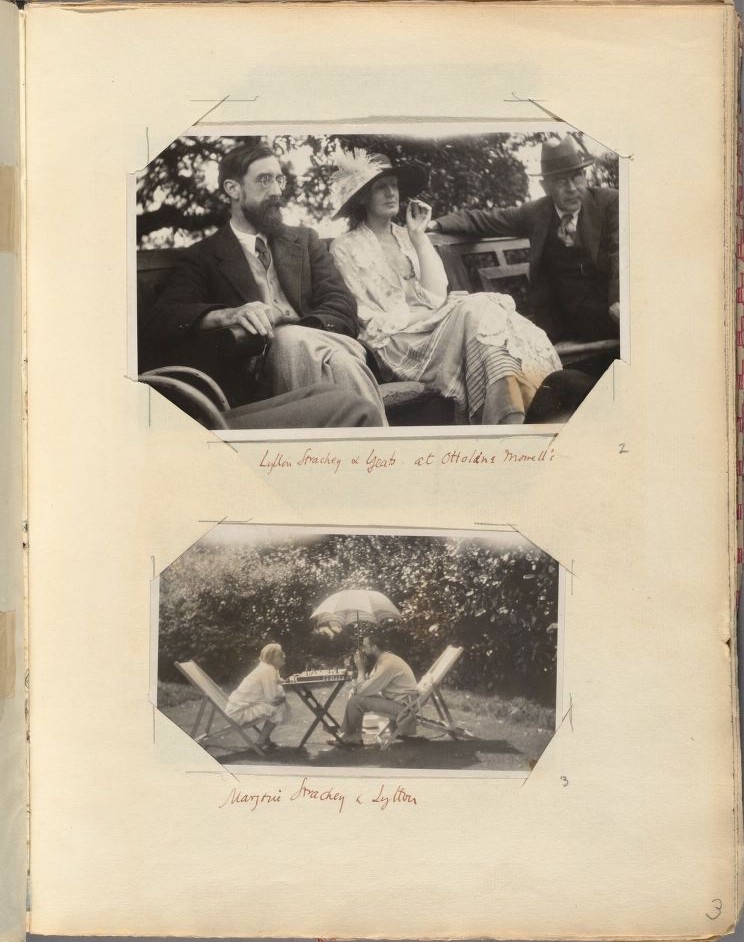

But there are many other ways to meet the author of Mrs. Dalloway and Jacob’s Room than traveling to her writer’s lodge, a tidy, tiny house on the Monk’s House grounds that served as her office. Like an avid Instragrammer—or like my mother and probably yours—Woolf kept careful record of her life in photo albums, which now reside at Harvard’s Houghton Library. The Monk’s House albums, numbered 1–6, contain images of Woolf, her family, and her many friends, including such famous members of the Bloomsbury group as E.M. Forster (above, top), John Maynard Keynes, and Lytton Strachey (below, with Woolf and W.B. Yeats, and playing chess with sister Marjorie). Harvard has digitized one album, Monk’s House 4, dated 1939 on the cover. You can view its scanned pages at their library site.

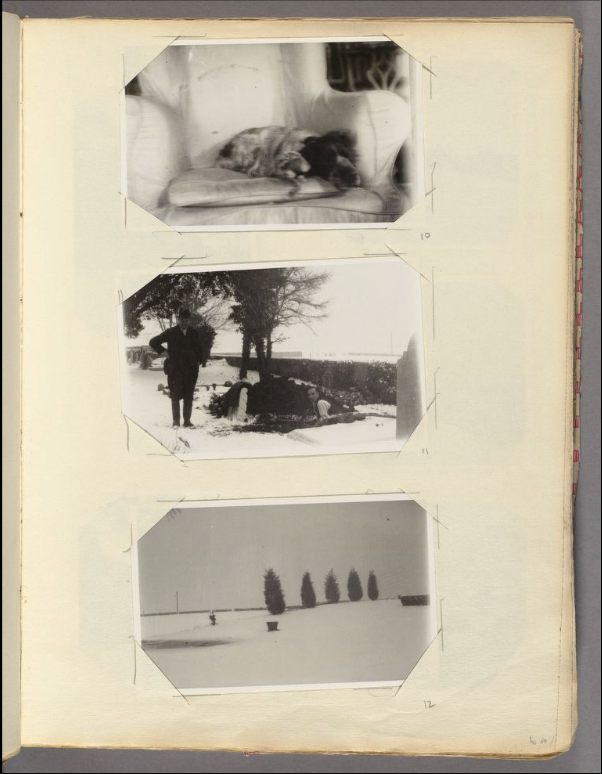

There are vacation photos and family photos; landscapes and photos of pets; clippings from newspapers and magazines; and, of course, the garden. The albums span the period 1890 to 1947 (including additions by Leonard after Virginia’s death). Many of the photos are labeled, many are not. Many of the albums’ pages are left blank. The photographs are arranged in no particular order. The net effect is that of a life recollected in pregnant images laced with lacunae, a psychological theme of so much of Woolf’s writing. Woolf, writes Maggie Humm, “believed that photographs could help her to survive those identity-destroying moments of her own life—her incoherent illnesses.”

But photography was also a means for cultivating relationships. Woolf “skillfully transformed friends and moments into artful tableaux, and she was surrounded by female friends and family who were also energetic photographers,” including her sister, Lady Ottoline Morrell, her friend and lover Vita Sackville-West, and her great aunt Julia Margaret Cameron. She “frequently invited friends to share her reflections. The letters and diaries describe a constant exchange of photographs, in which the photographs become a meeting-place, a conversation, aide-mémoires, and sometimes mechanisms of survival and enticement.”

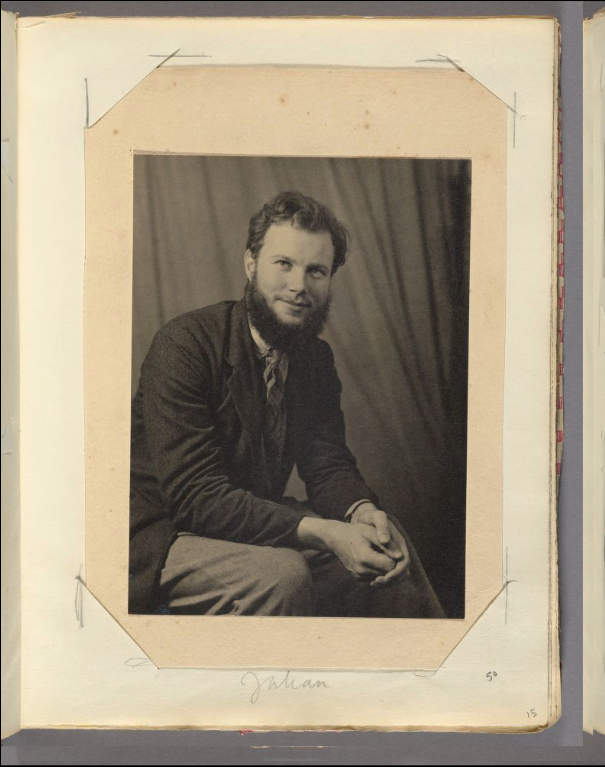

Unlike Monk’s House, a world built and shared with her husband, Woolf’s albums represent her own personal network of relationships. They serve as memorials and meditations after the deaths of those close to her. “Photographs of friends were important memento mori,” such as the portrait of poet Julian Bell, above, her nephew, who was killed in the Spanish Civil War. The photos document gatherings and important life events among her social circle. They perform all the tasks of ordinary photo albums, and more—showing us the “chain of perceptions” of which personal identity is made in Woolf’s modernist vision, with repetitions and sequences centered around familiar objects like her favorite chair.

For fans, avid readers, critics, and literary historians, the photographs provide a visual record of a life we come to know so well through the letters, diaries, and romans à clef. Writing to her sister, Woolf once described painting a portrait “using dozens of snapshots in the paint.” Visit her photo album here at the Harvard Library site, and flip through the pages of her life in snapshots.

Related Content:

An Animated Introduction to Virginia Woolf

The Steamy Love Letters of Virginia Woolf and Vita Sackville-West (1925–1929)

Why Should We Read Virginia Woolf? A TED-Ed Animation Makes the Case

Josh Jones is a writer and musician based in Durham, NC. Follow him at @jdmagness

Thank you for this. A minor correction: Lady Ottoline Morrell was a friend of Virginia Wolfe, not her sister. Her sister was Vanessa Bell, an artist.

Also, minor correction to you Patricia Downing. Virginia WOOLF is spelt WOOLF.…not Wolfe!!!!

Nice to be quoted. My Snapshots of Bloomsbury contains over 100 of these photographs fully annotated (Havard’s are not annotated) together with appropriate quotations — a better/more useful introduction than the quoted chapter if you want to read more. https://www.amazon.co.uk/Snapshots-Bloomsbury-Private-Virginia-Vanessa/dp/0813537061