We music fans of the increasingly all-digital 2010s take compact discs for granted, so much so that many of us haven’t slid one into a player in years. But if we cast our minds back, and not even all that far, we can remember a time when CDs were precious, and the medium itself both impressive and controversial. Back when it first came on the market in 1982 (packaged in longboxes, you’ll recall) it seemed impossibly high-tech, inspiring dreamily futuristic promotional videos like the one below and emerging from a process of development that required the combined R&D and industrial might of both Japan and Europe’s biggest consumer-electronics giants, Sony and Philips.

That years-long coordinated effort, as Greg Milner writes in Perfecting Sound Forever, saw a team of engineers from both companies “shuttling between Eindhoven and Tokyo,” the prototype CD player “given its own first-class seat on KLM.”

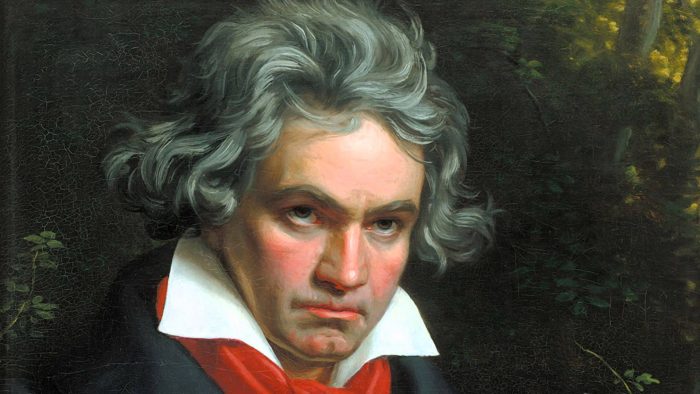

Milner also mentions that “Philips wanted a 14-bit system and a disc that could hold an hour of music, while Sony argued for 16 bits and 74 minutes, supposedly because that was the length of Beethoven’s Ninth Symphony,” though he calls the Beethoven bit “likely a digital audio urban legend.” But, like any urban legend, it contains grains of truth, though how many grains nobody quite knows for sure.

Philips’ preferred system would play 115-millimeter discs, while Sony’s would play 120-millimeter discs. As Wired’s Randy Alfred tells it:

When Sony and Philips were negotiating a single industry standard for the audio compact disc in 1979 and 1980, the story is that one of four people (or some combination of them) insisted that a single CD be able to hold all of the Ninth Symphony. The four were the wife of Sony chairman Akio Morita, speaking up for her favorite piece of music; Sony VP Norio Ohga (the company’s point man on the CD), recalling his studies at the Berlin Conservatory; Mrs. Ohga (her favorite piece, too); and conductor Herbert von Karajan, who recorded for Philips subsidiary Polygram and whose Berlin Philharmonic recording of the Ninth clocked in at 66 minutes.

Further research to find the longest recorded performance came up with a mono recording conducted by Wilhelm Furtwängler at the Bayreuth Festival in 1951. That playing went a languorous 74 minutes.

A good story, sure, but as Philips Engineer Kees A. Schouhamer Immink writes in a technical article marking the CD’s 25th anniversary, “everyday practice is less romantic than the pen of a public relations guru.” Whatever the influence of Beethoven, in 1979 “Philips’ subsidiary Polygram — one of the world’s largest distributors of music — had set up a CD disc plant in Hanover, Germany that could produce large quantities of CDs with, of course, a diameter of 115mm. Sony did not have such a facility yet. So if Sony had agreed on the 115mm disc, Philips would have had a significant competitive edge in the music market. Ohga was aware of that, did not like it, and something had to be done.”

How much does the running time of a CD, which would enjoy a long reign as the dominant media for recorded music, owe to what Immink calls “Mrs. Ohga’s great passion for [Beethoven],” and how much to “the money and competition in the market of the two partners”? Not even Snopes, which rules the claim of a connection between Beethoven’s Ninth and the development of the CD as “undetermined,” can settle the matter. But whatever determined the length of the albums in the CD era, that 74-minute runtime remains a strong influence on our expectations of album length even now that musicians can record and sell them at any length they like — and now that we the consumers can listen any way we like, fragmenting, re-arranging, and customizing all of our music experiences, even Beethoven’s Ninth.

Related Content:

How Did Beethoven Compose His 9th Symphony After He Went Completely Deaf?

How Steely Dan Wrote “Deacon Blues,” the Song Audiophiles Use to Test High-End Stereos

A Celebration of Retro Media: Vinyl, Cassettes, VHS, and Polaroid Too

Neil Young on the Travesty of MP3s

Based in Seoul, Colin Marshall writes and broadcasts on cities and culture. His projects include the book The Stateless City: a Walk through 21st-Century Los Angeles and the video series The City in Cinema. Follow him on Twitter at @colinmarshall or on Facebook.

nuostabus turinys, ačiū, kad pasidalinote šiuo tinklarasčiu .…